Discover more from Intimations of a New Worldview

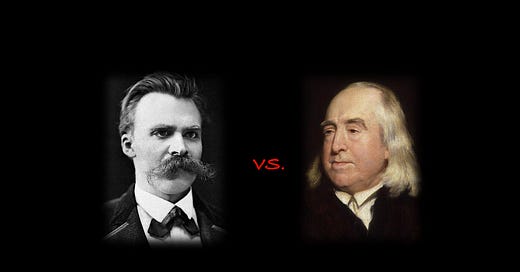

Utilitarianism is Slave Morality for Nerds

A scientific and Nietzschean demonstration of the matrix of morality.

*Note: This essay was originally written for Geoffrey Miller’s “Psychology of Effective Altruism” class. I have kept the APA formatting because it would take too much time to change every reference to a link. Fair warning, this is ~17,000 words long, not including references.

‘To deny morality' — this can mean, first: to deny that the moral motives which men claim have inspired their actions really have done so — it is thus the assertion that morality consists of [mere] words and is among the coarser or more subtle deceptions (especially self-deceptions) which men practise, and is perhaps so especially in precisely the case of those most famed for virtue. Then it can mean: to deny that moral judgments are based on truths. Here it is admitted that they really are motives of action, but that in this way it is errors which, as the basis of all moral judgment, impel men to their moral actions. This is my point of view… Thus I deny morality as I deny alchemy, that is, I deny their premises: but I do not deny that there have been alchemists who believed in these premises and acted in accordance with them. (Nietzsche, Daybreak 103)

I don’t believe in morality. Or, at least, I probably don’t believe in morality in the same way that you believe in it if you have been enculturated within the Western world. My disbelief in morality is probably less radical than it seems at first glance. I do believe, for example, that murderers, rapists, thieves, etc., should be condemned and punished. I also believe that many altruistic acts ought to be praised and encouraged. But I do not believe these things for what would typically be called moral reasons. As Nietzsche would go on to say in the same passage:

It goes without saying that I do not deny — unless I am a fool — that many actions called immoral ought to be avoided and resisted, or that many called moral ought to be done and encouraged — but I think the one should be encouraged and the other avoided for other reasons than hitherto. We have to learn to think differently — in order at last, perhaps very late on, to attain even more: to feel differently. (Daybreak 103)

And that is my position as well. We must learn to think and feel differently about morality, not (in the way that Steven Pinker [2018] once famously misinterpreted Nietzsche) so that we can all be egoistic sociopaths, but rather so that we can overcome the great dangers of being taken in by a mass hallucination. I will suggest at the end of this essay that there is another, more realistic way that we can think about morality (i.e., in terms of a process), but that this is very different from how most people currently understand it.

The psychologist Jonathan Haidt (2012) refers to moral systems as matrices. A matrix (in reference to the movies of the same name) is a consensual hallucination. That is precisely what I believe morality is. Morality is a collective, consensual hallucination. We implicitly agree to believe in (and act in accordance with) concepts like moral obligations, moral equality, and moral truths. But these concepts do not correspond to “moral facts”. Although acting in accordance with moral precepts might be useful (for yourself or for a group), these moral precepts do not refer to anything that exists outside of the minds, behaviors, and history of human beings. There is not, for example, some kind of Platonic realm containing moral facts, nor is there a transcendent God from whom moral facts emanate.

For example, moral philosopher Peter Singer has often argued that people have a moral obligation to give some of their income to impoverished people. This argument has almost certainly influenced people to actually give money to charity. But where does this moral obligation come from? Singer might say that it comes from the self-evident truth that all lives are morally equal. If we would be willing to save a drowning child in front of us, then we should also be willing to save a starving child thousands of miles away. But then I am compelled to ask: is it really self-evident that all lives are morally equal? Where does this moral equality come from? Is it built into the structure of the universe? Can it be discovered like a mathematical formula (e.g., the Pythagorean theorem)? Is it commanded to us by God? Was it also true 5,000 years ago, before the idea of “moral equality” had occurred to anyone (and when human sacrifice was nearly universal)? In asking these questions, of course, one risks being labeled a kind of moral pervert. You don’t believe in moral equality? Are you some kind of racist/sexist/nazi/whatever? And yet, despite widespread agreement in our own culture, the idea of moral equality would have been absurd to almost every human being who has ever lived. To Aristotle, for example, slavery was obviously good and necessary (Aristotle, 2013). Some people, Aristotle believed, were natural slaves (i.e., they were naturally fit for slavery), and this would likely have been the attitude of most Greek citizens. Furthermore, almost everyone throughout human history would have put the interests of their own family, group, tribe, etc., over the interests of others and would have seen deviation from this kind of group loyalty as morally dubious (Haidt, 2012). Why do we (as good, Western, educated people) assume moral equality so readily while most people throughout history would have found it laughable?

Despite its historical peculiarity, the assumption of moral equality is a key aspect of the moral matrix of Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democratic (WEIRD) society (Henrich, 2020; Siedentop, 2014). Almost all of us have unconsciously and implicitly agreed that people are morally equal, though what that means in practice is often unclear. As the founding fathers wrote in the Declaration of Independence, it is self-evident that all men are created equal (despite the fact that people are obviously not equal in any measurable way). This consensual hallucination has an effect on the real world. We readily talk to each other in terms of human rights, moral obligations, and moral arguments that are predicated upon the idea of moral equality. These kinds of arguments obviously affect people’s behavior. But does this widespread agreement mean that moral equality is “true” in some mind or culture-independent sense? If so, this would mean that every moral system in which moral inequality was the norm (i.e., every moral system that existed before the Axial age, and many after) is necessarily “false”. That would include the morality of the ancient Greeks and Romans, Indians, Aztecs, Egyptians, etc., all of which were predicated on an “order of rank” among men (Siedentop, 2014; Nietzsche, 1901).

This is what I deny. Moral equality is not “true” or “false”. The very idea that morality can be “true” or “false”, like the solution to a math problem, is itself a peculiar aspect of WEIRD psychology (Henrich, 2020). Applying “true” or “false” to morality is a category error, but it is a necessary error that is required to maintain the consensual hallucination that is our moral matrix. Moral matrices typically lead people to believe that their morality is true or objective. This belief in the objectivity of morality has a function. It serves to blind people to the coherence of alternative moralities.

Moral matrices bind people together and blind them to the coherence, or even existence, of other matrices. This makes it very difficult for people to consider the possibility that there might really be more than one form of moral truth, or more than one valid framework for judging people or running a society. (Haidt, 2012)

I basically agree with Haidt here, but I think he is misusing the word “truth”. If there is “more than one form of moral truth” then, in effect, there is no such thing as moral truth. There is not, for example, more than one form of truth about whether the sky is blue or whether 2 + 2 = 4. Saying that there is “more than one form of moral truth” is practically equivalent to saying that there are no moral truths. (To be clear, I think the big picture is more complicated than this, as I think there are in fact truths about the objective value of the process by which morality changes over time that one might reasonably call “moral truths”. I will briefly discuss this at the end of this essay).

Concepts like moral obligations and moral equality obviously affect people’s behavior. In that way they are real and have a real effect on the world. But, as Nietzsche suggested, these concepts are real in the same way that alchemy is real. Alchemy exists, of course, as a coherent belief system. And as a belief system, alchemy has clearly influenced people’s behavior. Many intelligent men spent years of their life studying alchemical texts and attempting to transmute lead into gold, etc. My claim, however, is that the influence of alchemy is based on an error. I deny the premises of alchemy (e.g., that base metals can be transmuted into gold). In the same way, I deny the premises of morality (e.g., that “moral equality” refers to any kind of timeless or objective truth), but I do not deny that morality can influence people’s behavior. I would simply suggest, as Nietzsche did, that this influence is based on an error (even when I think the behaviors being influenced are good!).

I do not believe that the error of morality is banal. I believe that this error, along with those who perpetuate it most vehemently (whom Nietzsche referred to as “the good and the just”), represents the greatest danger to the future of humanity.

Who represents the greatest danger for all of man’s future? Is it not the good and the just? Break, break the good and the just! O my brothers, have you really understood this word? (Nietzsche, Zarathustra III, 12. 27)

But why is morality so dangerous? There are multiple reasons, but in part it’s because the illusion of morality is the single greatest obstacle to the pursuit of truth, and truth is the meta-solution to every problem that will face humanity in the coming centuries. As Haidt put it:

Morality binds and blinds. This is not just something that happens to people on the other side. We all get sucked into tribal moral communities. We circle around sacred values and then share post hoc arguments about why we are so right and they are so wrong. We think the other side is blind to truth, reason, science, and common sense, but in fact everyone goes blind when talking about their sacred objects. (Haidt, 2012 p. 332)

Everyone goes blind when talking about their sacred objects. This doesn’t just refer to physical objects, but ideas, people, values, empirical beliefs, and anything else that human beings can treat as sacred. Morality-induced blindness is pervasive. Whether it’s the validity of presidential elections, the causes and consequences of COVID-19, the potential threat posed by climate change, or the war in Ukraine, my experience has been that otherwise intelligent people on both sides of the political aisle become monumentally stupid when reasoning about topics they are morally invested in. Similarly, otherwise intelligent scientists are prone to make wild errors of reasoning (e.g., assuming that correlation = causation) when analyzing evidence about morally charged topics.

There is plenty of empirical evidence suggesting that people become more biased when reasoning about morally charged topics (e.g., Tetlock et al., 2000). Perhaps even more alarming is the fact that, even when people notice these morality-induced biases in themselves, they don’t see any problem with them. In fact, when dealing with morally charged topics people often believe that their own biased reasoning is morally admirable and by extension that anyone who isn’t biased about a particular issue is morally suspect (Cusimano & Lombrozo, 2023). What must be understood is that morality-induced blindness is not some kind of bug associated with moral reasoning. Rather, it is a feature of moral reasoning. Morality must blind us to the coherence of alternative moral systems in order to play its proper role of binding us together into groups.

At the same time, morality-induced blindness is very likely to kill us. Authoritarian techno-states, artificial intelligence, nuclear war, engineered pandemics, and political unrest could all pose existential threats to human civilization in the coming centuries. We will be much more likely to solve problems around these issues if we are not rendered blind and stupid by our own moralization of them. This recognition of morality-induced blindness as a problem suggests that we need a critique of moral values, and most especially of our moral values. As Nietzsche put it more than 100 years ago:

This problem of the value of pity and of the morality of pity (—I am opposed to the pernicious modern effeminacy of feeling—) seems at first to be merely something detached, an isolated question mark; but whoever sticks with it and learns how to ask questions here will experience what I experienced—a tremendous new prospect opens up for him, a new possibility comes over him like a vertigo, every kind of mistrust, suspicion, fear leaps up, his belief in morality, in all morality, falters—finally a new demand becomes audible. Let us articulate this new demand: we need a critique of moral values, the value of these values themselves must first be called in question—and for that there is needed a knowledge of the conditions and circumstances in which they grew, under which they evolved and changed. (Nietzsche, Genealogy of Morals, I. 6)

This essay is meant to serve as a critique of morality in general, but in order to do that I will need to hone in on a narrower target. As Nietzsche suggested, in order to understand morality we need to understand the conditions and circumstances under which moral values have evolved and changed. In this case, I will analyze the conditions and circumstances which led to the emergence of utilitarianism. Utilitarianism is probably the most influential secular moral theory in the world today. It serves as the philosophical basis of the effective altruism movement, whose influence has directed billions of dollars towards causes related to animal welfare, global poverty reduction, combatting infectious diseases, and reducing existential threats. In a nutshell, utilitarianism says that the morally right action is the one that produces the most good. Not good for you, of course, but good for all humans or all sentient creatures. What counts as good? That is the subject of endless debates among utilitarians, but it’s not that important for my purposes. There are many versions of utilitarianism (mostly differing on what counts as good), but they all have the following characteristics:

Universalism: The same moral principles and obligations apply equally to everyone.

Equality: All human beings deserve equal moral consideration. That is, the well-being of all human beings counts equally (there are differing opinions among utilitarians about animals, e.g., whether the importance of their well-being should be weighted by their capacity to suffer, but we won’t consider those debates in detail here).

Consequentialism: The moral rightness of an action is determined by its consequences, not by the intentions of the acting agent.

Systemization: This is usually not made explicit by utilitarians, but the utilitarian way of understanding morality allows one to treat moral decisions like a math problem. One must simply try to calculate how much the overall well-being in the universe will increase or decrease because of a particular action or rule. This will be important later.

Utilitarian philosophers tend to be well aware of the philosophical problems posed by any attempt to provide a “rational” basis for morality or establish the existence of moral truths. There are a number of ways that utilitarians may attempt to circumvent these problems. For example, there are some utilitarians who do not believe in objective moral truths and do not claim that utilitarianism supplies any (Lazari-Radek & Singer, 2017). I agree, of course, and have no objection to this kind of utilitarianism (if they have a preference for using utilitarian calculus in their own decision-making, that is their prerogative). But if utilitarianism is a mere preference, then I would hardly call it a moral philosophy. Some utilitarians recognize that intuitions must necessarily underlie any moral philosophy, but claim that the intuitions underlying utilitarianism are “basic” and “nearly universal” (Montgomery, 2000). That’s clearly not true since the intuition underlying moral equality is extremely peculiar from a historical perspective. But even if the intuitions underlying utilitarianism really were “basic” and “universal”, it would tell us nothing about the truth or falsity (or rationality) of utilitarianism.

Harsanyi (1982) provides a pretty typical argument in favor of the “rationality” of utilitarianism. He claims that “utilitarianism is the only ethical theory which consistently abides by the principle that moral issues must be decided by rational tests and that moral behaviour itself is a special form of rational behaviour” (p. 40). In other words, utilitarianism is the only rational ethical theory. He supports this claim with a four-part argument (this summary is taken from Montgomery, 2000):

1) The preferences of people should follow Bayesian rationality.

2) Moral preferences should follow Bayesian rationality.

3) Moral preferences should follow Pareto optimality.

4) The preferences of different people should be given equal weight.

I won’t comment here on the first three axioms, since these can differ from argument to argument (and to say that people “should” follow Bayesian rationality is redundant since Bayesian rationality is optimal by definition). It is the fourth axiom, which is common to all such utilitarian arguments, which is snuck in the backdoor, as if somehow it is “rational” to give a random person’s preferences the same weight as your own, or your children, your friends, spouse, lover, etc. This axiom may appear rational to somebody who is steeped in WEIRD morality (and perhaps a few other moral traditions, e.g., Jainism), but to almost everyone else (especially those with pre-Axial age moral intuitions) this axiom would appear absurd, even laughable. For most people, you would be morally monstrous to give the same weight to the well-being of an outsider as to a group member or the same weight to a random person as to a close family member. The utilitarian, of course, would claim that these other moral intuitions are “irrational”, but hopefully the circularity of this claim is obvious.

Regardless of these philosophical dilemmas, in normal discourse utilitarians assume that utilitarian reasoning will give us the “correct” or “rational” moral decisions. My contention, however, is that there is no such thing as a “correct” or “rational” moral decision. Let me be clear. If you already have a moral value, there are clearly better and worse ways of pursuing that value, which one may want to call rational and irrational. But the value itself cannot be rationally derived in the way that a mathematical equation can, nor can it be discovered through observation like an empirical fact. Human values are the products of evolutionary and developmental processes for which the terms “rational” and “irrational” (or “correct” and “incorrect”) simply do not apply.

What utilitarianism actually provides is a rational justification of the moral intuitions of a particular kind of person: most typically, utilitarianism will be appealing to nerdy (i.e., relatively autistic), WEIRD individuals. I will explain what that means later on in this essay. As Nietzsche said in Beyond Good and Evil:

Gradually it has become clear to me what every great philosophy so far has been: namely, the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir … In the philosopher… there is nothing whatever that is impersonal; and above all, his morality bears decided and decisive witness to who he is… (BGE 6)

Utilitarianism is just this kind of involuntary and unconscious confession. Although utilitarianism cannot tell us anything about “moral truths”, it can certainly tell us something about the utilitarian. But what does it tell us? Most typically, the four characteristics of utilitarianism I laid out above (universalism, equality, consequentialism, and systemization) can tell us two things about the utilitarian:

1. The first two characteristics (universalism and equality) tell us that the utilitarian has internalized the foundational tenets of slave morality.

2. The third and fourth characteristics (consequentialism and systemization) tell us that the utilitarian is likely to be a little bit of a nerd (i.e., a little bit autistic, and maybe more than a little bit).

In other words, utilitarianism is slave morality for nerds. In order to really understand what utilitarianism is (as the unconscious confession of its proponents), we will need to understand the emergence of utilitarianism at multiple time-scales. We must understand the emergence of morality in general (as a result of genetic evolution over millions of years), the emergence of slave morality in particular (as a result of cultural evolution over thousands of years), the impetus that led to the emergence of utilitarianism and other attempts to provide a rational basis for morality in the 18th century (i.e., the loss of faith in Christianity as a foundation for morality), and finally the individual difference factors that make utilitarianism appealing to some and unappealing (even repulsive) to others, which can tell us about the development of utilitarianism in the context of a single lifetime. A book could be written about each of these topics, so I will have to be brief. Nevertheless, each of these levels of analysis is important for gaining a full understanding of the emergence of utilitarianism, which will in turn help us to understand the emergence of all such moral ideals.

The Evolution of Morality

Evolutionary scientists have been trying to understand the function and phylogeny of human morality since Darwin. Here I’m not going to review that intellectual history (which is fascinating), but rather summarize the most plausible account that I’ve come across, which was given by Michael Tomasello in his (2016) book A Natural History of Human Morality. Tomasello suggests that the unique aspects of human morality evolved to maintain and facilitate large-scale positive sum interactions (i.e., interdependent relationships). If you’ve read my Intimations essay (B. P. Andersen, 2022b), it will probably be clear why Tomasello’s account makes the most sense to me (since in that essay I argue for the importance of non-zero-sum interactions in human evolution).

Many species, especially mammals, engage in behaviors that can be called altruistic. Mammalian mothers, for example, feed their children at great cost to themselves. In many species this sympathetic care can be directed towards non-kin as well. Chimpanzees, for example, may show sympathy towards a long-time friend/ally who gets injured. Tomasello refers to this kind of altruism as the morality of sympathy. In contrast to Tomasello, I wouldn’t be inclined to call this kind of behavior “moral”. In my opinion a mother feeding her child is not a “moral” act (as Nietzsche aptly put it, everything done out of love occurs beyond good and evil). But there’s no need to argue semantics here. The morality of sympathy, as described by Tomasello, is present in all mammals and it’s fairly simple to understand how it evolved. The normal evolutionary principles of kin altruism (i.e., altruism directed towards genetic relatives) and reciprocal altruism (i.e., “you scratch my back, I scratch yours”) suffice to explain the morality of sympathy.

Humans, however, do something different, which is unique to our species. We engage in what Tomasello refers to as the “morality of fairness”. We feel obligated to act in accordance with moral obligations, duties, rights, and principles of justice. We readily use terms like these to describe our social obligations. Tomasello suggests that this kind of morality evolved to deal with problems related to large-scale cooperation. Because human beings are both self-interested (i.e., we have “selfish” goals such as status-seeking, being sexually attractive, attaining resources, etc.) and extremely cooperative, we often find ourselves in complex situations where the competitive and cooperative motivations of different individuals are at odds with each other. For example, each individual within a group may have a motivation to be dominant over others, but unfettered competition for dominance would be detrimental to the group as a whole.

The morality of fairness is thus much more complicated than the morality of sympathy. Moreover, and perhaps not unrelated, its judgments typically carry with them some sense of responsibility or obligation: it is not just that I want to be fair to all concerned, but that one ought to be fair to all concerned. In general, we may say that whereas sympathy is pure cooperation, fairness is a kind of cooperativization of competition in which individuals seek balanced solutions to the many and conflicting demands of multiple participants’ various motives. (Tomasello, 2016 p. 2)

Tomasello has a compelling hypothesis about how the morality of fairness evolved. First there was an initial step in which we gained the ability to share our attention with other individuals. He calls this “shared intentionality”. This capacity for shared intentionality allowed us to cooperate in a way that our cousins the chimpanzees are simply incapable of (despite many attempts at training them to do so). We are naturally capable of sharing our attention with another person in the service of a shared goal. At a certain stage of development, children will automatically understand what somebody means when they point at something (i.e., we are going to both direct our attention at this object) in a way that chimpanzees never really “get”.

Tomasello points out that when two people collaborate with each other in service of a shared goal, they come to depend on each other. This dependence comes with a feeling of obligation. I may feel obligated to be a reliable partner with my collaborators because I also depend on them and their continued cooperation. Furthermore, the welfare of my collaboration partner is of genuine interest to me. If they die or are seriously injured then I am worse off for it. For this reason, we have also evolved to feel genuine sympathetic concern for those we tend to cooperate with or rely on (i.e., our friends). This feeling of obligation and sympathy in the context of collaborative partnerships is what Tomasello refers to as “dyadic” or second-person morality.

Humans, however, do not just cooperate in small groups or dyads, but can come together with thousands of unrelated individuals in the service of a shared goal (e.g., warfare, building projects, the performance of rituals, etc.). This required moving from “shared intentionality” to “collective intentionality”, which involved the creation of social norms, institutions, and conventions. The adoption of these norms is supported by what Chudek and Henrich (2011) refer to as our “norm psychology”. Chudek and Henrich review evidence that human children naturally and instinctually conform to (and later on enforce) the moral norms of their group:

Young children show motivations to conform in front of peers, spontaneously infer the existence of social rules by observing them just once, react negatively to deviations by others to a rule they learned from just one observation, spontaneously sanction norm violators and selectively learn norms (that they later enforce) from older and more reliable informants. Children also acquire context-specific prosocial norms by observing others perform actions consistent with such norms and spontaneously (without modeling) enforce these norms on other children. Such norm acquisition endures in retests weeks or months later. (p. 223)

This transition from second-person morality (with personal obligations) to a third-person morality facilitating large-scale cooperation (with group obligations in the form of norms and institutions) was the next step in the evolutionary process leading to the modern understanding of morality.

To coordinate their group activities cognitively, and to provide a measure of social control motivationally, modern humans evolved new cognitive skills and motivations of collective intentionality—enabling the creation of cultural conventions, norms, and institutions… based on cultural common ground. Conventional cultural practices had role ideals that were fully “objective” in the sense that everyone knew in cultural common ground how anyone who would be one of “us” had to play those roles for collective success. They represented the right and wrong ways to do things…

It was a kind of scaled-up version of early humans’ second-personal morality in that the normative standards were fully “objective,” the collective commitments were by and for all in the group, and the sense of obligation was group-mindedly rational in that it flowed from one’s moral identity and the felt need to justify one’s moral decisions to the moral community, including oneself. In the end, the result of all of these new ways of relating to one another in collectively structured cultural contexts added up for modern humans to a kind of cultural and group-minded, “objective” morality. (Tomasello, 2016 pp. 5-6)

Note that Tomasello consistently puts the word “objective” in scare quotes. He is explaining how it is that human beings came to perceive moral norms as objective. What do we mean when we refer to objectivity? In part it is a recognition of the obvious fact that if more than one person perceives a certain phenomenon it is more likely that the phenomenon is real. If Joe the caveman sees an antelope but his caveman buddies don’t see it, it’s possible that all Joe actually saw was the rustling of the grass. But if Joe and all of his buddies see the antelope we can be pretty sure that there was an actual antelope there. Thus, the more perspectives we can bring to bear on a phenomenon the more “objective” we can be about it.

Nevertheless, what we mean by objectivity in normal discourse isn’t just a simple “adding up” of multiple perspectives. If it is objectively true that there are three apples in a basket, we mean that it is true not just from multiple perspectives but from any possible perspective. In an earlier book, Tomasello (2014) made the fascinating claim that at some point in human evolution this understanding of objectivity combined with our norm psychology to encourage the belief that our group norms were objective parts of an external reality:

We are not talking here about an individual perspective somehow generalized or made large, or some kind of simple adding up of many perspectives. Rather, what we are talking about is a generalization from the existence of many perspectives into something like “any possible perspective,” which means, essentially, “objective.” This “any possible” or “objective” perspective combines with a normative stance to encourage the inference that such things as social norms and institutional arrangements are objective parts of an external reality. (p. 92, my emphasis)

A similar idea was put forward by Kyle Stanford (2018) in a Behavioral and Brain Sciences article. Stanford asks why it is that humans so often perceive moral norms as “objective” or “externally imposed”. Stanford comes to a very similar conclusion as Tomasello. He suggests that the objectification of morality “represents a mechanism for establishing and maintaining correlated interaction under plasticity…” (p. 8). In other words, we objectify morality because doing so helps us to navigate the complexities of cooperating in large groups while avoiding exploitation. By objectifying morality, we can think of moral values as being independent of contingent human circumstances (e.g., if “the well-being of all sentient creatures” is morally good, as the utilitarians would have it, then it must be good in itself regardless of circumstances or perspective). However, if different groups objectify different moral norms and values (which they clearly do), they can’t all be “objectively” correct.

It’s not difficult to imagine how this perceived objectivity may have initially emerged. What if, for example, almost everyone you had ever known was in full agreement that eating chicken is morally wrong? What if they all acted as if this was as true and obvious as the observation that the sky is blue? Would it not appear as though that moral claim was “objective” in some sense? Isn’t it the case that you generally determine the “objectivity” of a phenomenon based on whether multiple people can perceive it? If everyone in your group perceives something as obviously true, and you don’t, wouldn’t that make you the crazy one in the eyes of your group? “Crazy” is how we would think of someone who insisted that the sky is green. The same label is often applied to those who do not share our moral matrix. That is, we tend to treat people who don’t share our moral matrix as if they were insisting (against all reason and evidence) that the sky is green. Despite the lack of moral consensus in our own culture, people are still prone to treat moral disagreements as if they are disagreements about obvious objective realities.

We have retained the intuition that morality is, in some sense, objective, but we have probably never understood the true origins of this intuition. Nevertheless, when asked to account for the objectivity of our own morality we must have some rational justification for it. For this reason we have (rather creatively) come up with many different kinds of rationalizations to justify the objectivity of our own morality. Moralizing Gods, karma, Kant’s “categorical imperative”, and arguments like the one I reviewed earlier for utilitarianism are all attempts to justify the perceived objectivity of morality. If the evolutionary story told by Michael Tomasello or Kyle Stanford is true, all such attempts must ultimately fail. The reasons we come up with to justify the perception that our morality is objective are all post-hoc rationalizations (we will come back to this issue in the section on secular moral philosophies). The true reason we perceive our morality as objective is that this propensity was selected for through biological and cultural evolutionary processes.

The Cultural Evolution of Slave Morality

After our “objective” third-person morality was off the ground, a different kind of evolutionary force began to exert its effect on humanity. We had evolved the ability and propensity to create norms, institutions, and conventions (moral or otherwise) to bind our groups together and facilitate their cooperation. But the content of these norms, institutions, and conventions could differ widely from group to group. Different groups worshipped different gods, enforced different taboos, and adhered to different moral obligations regarding sex, kinship, and out-groups. These differences were not inconsequential. If a group adopted a norm that (for whatever reason) was especially functional, in the sense that it was especially good at promoting the expansion of that group, then that group and the norm associated with it would be more likely to proliferate into the future. Given that norms and institutions are often difficult to transmit between groups, the differential effect of norms and institutions on group success would produce a kind of selection effect. This is known as cultural group selection (Richerson et al., 2016).

Cultural group selection is not fully separable from genetic selection. It may be the case, for example, that genetic differences between groups contribute to one group adopting norms that another group wouldn’t. Nevertheless, very few people would argue that cultural differences are entirely determined by genetic differences. For example, the cultures of North and South Korea are wildly different despite very similar genetic backgrounds.

Regardless of the reasons for why different groups adopt different norms and institutions, we can analyze the effect that these norms and institutions have on the success of the group. As an example, Henrich and colleagues (2012) argued that the adoption of monogamous norms by Christianity was a major contributor to later European success. Historically, most groups have allowed for polygamy. The fact that Christianity banned polygamy contributed to Western success for at least two major reasons: 1) Polygamous societies default to polygyny (one man with multiple women) and this means they end up with a lot of “leftover” men who have no chance of ever getting married. On average, these leftover men attempt to climb the social hierarchy (and get laid) by any means necessary, including violence and coercion. 2) Married men with children see a drop in testosterone (Henrich, 2020). This reduction in testosterone “tames” them and makes them more open to positive-sum interactions. High testosterone is associated with physical aggression, zero-sum attitudes, and antisocial behavior in general. In other words, when men marry and have children they are more likely to “settle down” and become peaceful cooperators. For these reasons, Henrich suggests, monogamous norms cause a society to become more peaceful and internally coherent. This peace allows for economic growth, which facilitates more success in intergroup competition. If this hypothesis is correct, the spread of monogamous norms would be an instance of cultural group selection.

In order to understand the emergence of what Nietzsche referred to as “slave morality” (of which Christian morality is the most prominent example), we must analyze what happened to human civilizations at two key points in time: 1) during the few thousand years after the agricultural revolution, and 2) during the Axial age (~900-300 BC), in which multiple religious and moral revolutions occurred across the ancient world. If you’ve read part 2 of my Nietzsche series, some of this will be familiar.

The Advent of Agriculture and Master Morality

The advent of full-blown agriculture caused many human groups to become stationary rather than nomadic. This transition massively changed the nature of human social life. In the first place, it eventually allowed some individuals and families to become dominant in a way that simply wasn’t possible in nomadic groups. In nomadic hunter-gatherer groups, one could just abandon a wannabe dominant individual and find new hunting and raiding partners. If an individual was a real nuisance, you could get your buddies together and stick a few spears in his belly while he is sleeping (Boehm, 2001). But the transition to stationary life changed this. Some individuals were able to amass land, weapons, loyal allies, and other resources in a way that allowed them to exert total domination over others. This dynamic eventually led to the rise of “God-kings” in the ancient world who had absolute authority over their subjects, a concept that would be unthinkable among hunter-gatherer groups.

For example, when the Hawaiian islands were first discovered, Hawaii was ruled as a chiefdom. The British explorers described the absolute tyranny the chiefs exerted over their people.

The great power and high rank of Terreeoboo, the [king of Hawai’i], was very evident, from the manner he was received at Karakakooa, on his first arrival. All the natives were seen prostrated at the entrance of their houses… The power of the [chiefs] over the inferior classes of people appears to be very absolute. Many instances of this occurred daily during our stay amongst them, and have been already related. The people, on the other hand, pay them the most implicit obedience, and this state of servility has manifestly had a great effect on debasing both their minds and bodies. (James King, 1809; quoted from Turchin, 2016 pp. 131-132)

As is often the case among these early agricultural societies, women were especially tyrannized by the men in charge.

Here [the women] are not only deprived of the privileges of eating with the men, but the best sorts of food are tabooed or forbidden to them. They are not allowed to eat pork, turtle, several kinds of fish, and some species of plantains; and we were told that a poor girl got a severe beating, for having eaten on board our ship, one of these forbidden articles. (James King, 1809; quoted from Turchin, 2016 p. 132)

The chiefs would also choose the most beautiful common girls to join their concubines. Presumably this arrangement was not voluntary. Hawaii is just one example of ethnographic evidence indicating the tyrannical nature of some archaic societies.

There is also genetic evidence that can inform us about the extent of the tyranny after the advent of agriculture. Karmin and colleagues (2015) documented a “bottleneck” in Y-Chromosome diversity corresponding to the advent of agriculture. To put their findings in simple terms, they provide genetic evidence that the operational sex ratio shot up from 3:1 (i.e., 3 successfully reproducing women for every 1 successfully reproducing man) to 17:1 after the advent of agriculture about 10,000 years ago. If their findings are reliable, this means that there was a period of time after the advent of agriculture when a few men were having a lot of children while the large majority of men died before having any children. While we cannot prove that this was due to the more dominance-based social arrangement brought about by agriculture, these authors suggest that this is the most likely explanation (although Zeng et al., 2018 disagrees with this explanation).

In summarizing the evidence about early societies after the advent of agriculture, Turchin (2016) had this to say:

The first large-scale complex societies that arose after the adoption of agriculture—“archaic states”—were much, much more unequal than either the societies of hunter-gatherers, or our own. Nobles in archaic states had many more rights than commoners, while commoners were weighed down with obligations and slavery was common. At the summit of the social hierarchy, a ruler could be “deified”—treated as a living god. Finally, the ultimate form of discrimination was human sacrifice—taking away from people not only their freedom and human rights, but their very lives. (pp. 132-133)

Plenty of ethnographic evidence has documented the fierce “egalitarian ethos” of most hunter-gatherer groups (Boehm, 2001, 2012). Judging by the resentment typically expressed towards bullies and upstarts among hunter-gatherers, we can assume that those who became subjugated in these early agricultural societies did not do so voluntarily. Turchin (2015) documents the poetry, art, and other cultural artifacts of early agricultural societies in which commoners expressed their resentment towards the nobility (e.g., calling them “large rat” or “devourer of peasants”).

It's clear that this dominance-based arrangement didn’t benefit everyone in the group. To be a low-status man in one of these archaic groups was an evolutionary dead end. So how did this arrangement happen without those of low status rebelling? We know that this kind of dominance didn’t emerge immediately after the advent of agriculture. There were a couple thousand years where arrangements remained relatively egalitarian. To make a long story short, Turchin suggests that there was a selection effect: larger groups tended to be more hierarchical (likely because hierarchy is necessary for managing larger groups) and larger groups tended to outcompete (e.g., conquer and enslave) smaller groups. Norms and institutions that helped to facilitate increased size (and therefore hierarchy) would have been selected for in this way. Over time, larger and more hierarchical arrangements became the norm due to cultural group selection.

Nietzsche’s “master morality” began as the morality of the nobility in these kinds of groups. I discussed the differences between master and slave morality at length in parts 2 and 3 of my Nietzsche series so I will be brief here. For our purposes, there are two ideas that are important to understand about master morality. The first is that it is characterized by an “order of rank” in which some people are considered naturally superior to others. The second is that those with power (i.e., the masters) don’t need to justify their preferences to anyone. They simply enact them. The masters say: we are the happy ones, the noble ones, the god-like ones, the good, and they (the subjugated or common people) are the unhappy, the rabble, the bad. What is the evidence for that? Well, just look at us!

Master morality therefore has very little need for metaphysical justification in the form of complicated moral theories or big, moralizing Gods. The moral preferences of the masters (which tend to focus on being proud, honorable, brave, war-like) are justified by the power of the masters. The gods of master morality are a reflection of the masters themselves. Cultures predicated on master morality (e.g., ancient Greek and Roman culture) don’t stand in a master-servant relation to their gods as in late Judaism and Christianity. Gods do not typically act as moral judges for the masters. Zeus, the king of the Greek gods, was an unfaithful rapist and murderer, but he was also a badass who defeated the Titans. The masters (given their very high opinion of themselves) tend to posit gods that reflect their own characteristics, moral or otherwise.

To be clear, not every society that displayed what Nietzsche would call “master morality” was as despotic as the Hawaiian society discussed earlier. The ancient Greeks, for example, were not nearly as tyrannical towards common people (at least from what we can tell based on limited evidence; see Bellah, 2011). Nevertheless, what sets master morality apart is the idea that some people really are considered aristoi (Greek for “best”, the origin of aristocracy), chosen by the gods, descended from the gods, etc., and are therefore superior to common men. As Nietzsche put it, master morality is predicated on an “order of rank”, the idea that people are most definitely not equal, morally or otherwise.

Starting in about 900 BC, there was a series of moral and religious revolutions across the ancient world, many of which posed a direct challenge to master morality. This is the beginning of the Axial age.

The Axial Age and Slave Morality

The dominance-based hierarchies of archaic groups allowed them to scale up in size, which made them better at waging war. It turns out, however, that dominance-based hierarchies come with some problems. In the first place, desperate and oppressed people tend to rebel every once in a while. This rebellion is costly and limits the size of empires (since rebels would tend to come from the edges of an empire). Second, and perhaps more importantly, is the fact that oppressed people and slaves don’t make for very good soldiers. It turns out that people don’t tend to fight bravely for their tyrannizers and that this was actually an important factor on ancient battlefields. It is largely for these reasons, Turchin suggests, that new forms of social organization, with new religious institutions, began to arise and proliferate during the Axial age:

Around 2,500 years ago, we see qualitatively new forms of social organization—the larger and more durable Axial mega-empires that employed new forms of legitimation of political power. The new sources of this legitimacy were the Axial religions, or more broadly ideologies, such as Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Confucianism (and later Christianity and Islam). During this time, gods evolved from capricious projections of human desire (who as often as not squabbled among themselves) into transcendental moralizers concerned above all with prosocial behavior by all, including the rulers.

The most remarkable feature of all the Axial religions is the sudden appearance of a universal egalitarian ethic, credited by Bellah to “prophet-like figures who, at great peril to themselves, held the existing power structures to a moral standard that they clearly did not meet.” Bellah calls these figures, who scorned riches and passed harsh judgment on existing social conditions, “renouncers” (and, in their fiercer strain, “denouncers”). (Turchin, 2015 pp. 190-191)

This “universal egalitarian ethic”, which is necessarily opposed to the “order of rank” characterizing master morality, is the beginning of what Nietzsche would call slave morality. What’s important to understand about this is that slave morality emerged at a particular time for particular reasons. At a psychological level, it was driven by the resentment of those who were, for whatever reason, stuck on the bottom rung of the social hierarchy (as expressed by the renouncers and denouncers). This resentment must have always been there, though, and there must be some reason it came to the fore in the Axial age rather than sometime before that. Zooming out, Turchin suggests that around the time of the Axial age, new technologies were changing the way war was waged and this in turn necessitated the adoption of new forms of social organization. Even the elites of the time noticed this necessity and so even they were open to the message of the renouncers and denouncers.

In particular, the invention of horseback archers by the peoples of the Eurasian steppe required the surrounding empires to adapt or die. Some of them did not adapt and they did not last long. Others innovated, both technologically and ideologically. Turchin describes the dilemma that was created by horseback raiders for the surrounding agrarian empires:

Should they try to protect all settlements, while running the risk of being picked off piecemeal? Or should they concentrate all their troops and abandon the countryside to the plunderers? There was only one way out of this quandary: drastically to increase the size of the state. More population translates into greater numbers of recruits for the army and a larger taxpaying base to support the soldiers. With more soldiers, the state can both garrison the forts and field an army large enough to chase the raiders away. Larger states could also construct “long walls” to protect themselves from the nomads (of which the Great Wall of China is the most spectacular example). This is why we see a qualitative jump in the size of states during the Axial Age. (p. 201)

The new “egalitarian ethic” adopted by Axial age empires allowed them to expand in a way that the dominance-based societies never could. Emperors began to adopt a stance of compassion towards their people rather than treating them like expendable property. In some cases this compassionate stance may have been superficial, but the core change was that there was now an expectation that emperors were supposed to act as if they cared about the well-being of their subjects (whereas before, there was no expectation that a God-king would show any regard for his inferiors). This new egalitarian ethic promoted voluntary cooperation rather than fear-based coercion and empires predicated on voluntary cooperation could scale up in a way that the dominance-based ones could not.

As Turchin alludes to above, the egalitarian ethic of slave morality required a new kind of religion. Gods are transformed from projections of our own characteristics to “transcendental moralizers concerned above all with prosocial behavior”. This is fairly easy to understand. The masters are powerful enough to enact their moral preferences without the need for any kind of divine justification. The gods of the masters are simply reflections of themselves. But what if you are not powerful? What if you are one of the oppressed? Without power, how can you justify your preferences?

You must transform your preferences into something else. They are no longer your preferences, but rather the preferences of a transcendent God or of the universe itself. What does God want? God wants everyone to be held to the same moral standard, for everyone to be compassionate towards the weak and helpless, and for everyone to be equal. This is, of course, an appealing conception of God if you are at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Although we can find the seeds of slave morality in the Jewish prophets (who railed against the rich and powerful for being greedy or hypocrites), in the Buddhist notion of universal compassion, in the Jainist regard for all sentient beings, and in other Axial age religions and ideologies, the ultimate culmination of slave morality was Christianity. The apostle Paul made clear that all Christians, regardless of the circumstances of their birth, were equal in the eyes of God.

There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul provides us with the quintessential expression of the slave revolt in morals:

Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things — and the things that are not — to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him. (1st Corinthians 1:27)

For the ancient Greeks, somebody was said to be “favored by the gods” if they were an especially powerful warrior or cunning leader. Christianity inverts this equation. For the Christians, God favors the foolish, weak, lowly, and despised. The Christian narrative is well-suited for supporting this inversion of master morality. In order to really understand the effect that Christianity had on morality in the ancient world, we must understand just how radical the Christian narrative was in the context of the Roman world in which it emerged. For the Romans, gods were powerful entities who typically inflicted suffering on their enemies. In the Christian narrative, God manifests as an unfairly oppressed victim upon whom suffering is inflicted. The historian Tom Holland (2019) described the Roman reaction to the Christ narrative:

[In the Roman world, divinity] was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings. Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque. (p. 6)

In the Roman world, crucifixion was a form of punishment that was usually reserved for disobedient slaves. The Christian God therefore took the form of a man who is morally perfect and is nevertheless subjected to a form of torture and death commonly used to punish disobedient slaves. The moral message couldn’t be any clearer.

The slave revolt in morals has been so thoroughly victorious in the Western world that we often define morality in terms of slave morality. This means that many WEIRD people think that a code of behavior that is not universalist and does not posit moral equality is not really morality. But if morality is a universal human propensity, this must be a mistake. We cannot take an idiosyncrasy of our culture (which only began to emerge 2,500 years ago) and then use that idiosyncrasy to measure other cultures. Even during the Axial age, most civilizations were not fully universalist and did not fully accept moral equality.

Although we see an egalitarian ethic emerge across the world during the Axial age, it is with Christianity that slave morality — universalism and moral equality — becomes truly victorious. Although some people will point to the existence of colonialism and slavery as evidence that Christians didn’t really adhere to this kind of morality, what must be understood is that Western civilization was the first large civilization in history to ban slavery and fight a major war over it. Before Western civilization, the morality of slavery wasn’t even a question (some individuals questioned it, but it had never become a divisive cultural issue). Furthermore, we are the only civilization in which there seems to have been any kind of moral dilemma about our colonization of other peoples. People point to the existence of inequality and conquest in the history of Western culture as evidence of its moral corruption, but don’t seem to realize that all large civilizations engaged in slavery and conquest. The fact that our history of slavery and conquest are widely seen as problematic is a testament to Western culture’s internalization of slave morality.

The Death of God and the Rise of Secular Moral Philosophies

After Buddha was dead, his shadow was still shown for centuries in a cave — a tremendous, gruesome shadow. God is dead; but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown. — And we — we still have to vanquish his shadow, too. (Nietzsche, The Gay Science 108)

Jonathan Haidt’s (2001) paper The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment represented a turning point in the study of moral psychology. The rationalists, who had dominated moral psychology since the cognitive revolution in the 1950s, argued that moral development was the result of increasingly sophisticated moral reasoning. In a nutshell, the rationalists believe that moral reasoning causes moral judgement. Haidt inverted this theory. Haidt reviews a wealth of evidence indicating that moral reasoning typically occurs after a moral judgement has already been made. In Haidt’s view, moral reasoning takes place so that we can justify our intuitive moral judgements to other people. Moral reasoning itself contributes very little (and often nothing) to the actual decision-making process. Mercier and Sperber (2011; Sperber & Mercier, 2017) later generalized this theory by suggesting that the function of all reasoning is argumentative.

Haidt reviews evidence that people have automatic emotional reactions to moral dilemmas. These emotional reactions (and not articulable reasons) are the true proximate cause of moral judgements. But where do these automatic emotional reactions come from? Haidt recognizes that moral intuitions are partially innate (in the sense that all normally developing children develop some similar moral intuitions) but at the same time moral intuitions can vary widely from culture to culture. Haidt summarizes his theory of moral development as such:

Moral development is primarily a matter of the maturation and cultural shaping of endogenous intuitions. People can acquire explicit propositional knowledge about right and wrong in adulthood, but it is primarily through participation in custom complexes involving sensory, motor, and other forms of implicit knowledge shared with one's peers during the sensitive period of late childhood and adolescence that one comes to feel, physically and emotionally, the self-evident truth of moral propositions. (p. 828)

The term “custom complex” is meant to capture the idea that cultural inheritance includes much more than verbal beliefs about the right and wrong way of doing things. Much of our cultural knowledge is passed on implicitly and unconsciously through imitation and practice.

Haidt’s theory is brilliant but not entirely original. Nietzsche made nearly the exact same argument about the role of reasoning in moral judgement more than 100 years before Haidt’s theory was published:

It is clear that moral feelings are transmitted in this way: children observe in adults inclinations for and aversions to certain actions and, as born apes, imitate these inclinations and aversions; in later life they find themselves full of these acquired and well-exercised affects and consider it only decent to try to account for and justify them. This `accounting', however, has nothing to do with either the origin or the degree of intensity of the feeling: all one is doing is complying with the rule that, as a rational being, one has to have reasons for one's For and Against, and that they have to be adducible and acceptable reasons. To this extent the history of moral feelings is quite different from the history of moral concepts. The former are powerful before the action, the latter especially after the action in face of the need to pronounce upon it. (Nietzsche, Daybreak 34)

For both Haidt and Nietzsche, moral judgement comes first and reasoning comes along afterwards to justify that judgement to other people. This understanding of the role of moral reasoning will be necessary for understanding what happened during the period known as the “enlightenment” when many Western intellectuals began to doubt the validity of Christian metaphysics. Christian metaphysical beliefs served as a justification of Christian morality. Christianity did this largely though its positing of an “equality of souls”. Although we may be profoundly unequal in this life, the New Testament suggests that we are all equal as children of God. In his (2014) book Inventing the Individual, Larry Siedentop does a great job of tracing this idea from its origins in early Christianity, to its expression by the church fathers and medieval canon lawyers (who were far more egalitarian in their outlook than many people would expect), all the way to its secular manifestations during the enlightenment. In summarizing his argument, Siedentop (2014) states:

Like other cultures, Western culture is founded on shared beliefs. But, in contrast to most others, Western beliefs privilege the idea of equality. And it is the privileging of equality – of a premise that excludes permanent inequalities of status and ascriptions of authoritative opinion to any person or group – which underpins the secular state and the idea of fundamental or ‘natural’ rights. Thus, the only birthright recognized by the liberal tradition is individual freedom. Christianity played a decisive part in this. Yet the idea that liberalism and secularism have religious roots is by no means widely understood. (p. 349)

I would go farther than Siedentop and say that not only are the origins of liberalism and secularism widely misunderstood, but liberal secular people are often actively hostile towards the idea that their own moral commitments have anything at all to do with Christianity (which they tend to associate with backwards fundamentalists).

Nietzsche also famously argued that secular liberal values emerged out of Christianity. In commenting on the “English” moralists, he pointed out that they have retained Christian moral intuitions but have forgotten their origin:

When the English actually believe that they know “intuitively” what is good and evil, when they therefore suppose that they no longer require Christianity as the guarantee of morality, we merely witness the effects of the dominion of the Christian value judgment and an expression of the strength and depth of this dominion: such that the origin of English morality has been forgotten, such that the very conditional character of its right to existence is no longer felt. (Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols)

This is what has happened across the Western world. We take for granted concepts like human rights, equality, and democracy without fully understanding the historical peculiarity of these ideas or the historical process by which they emerged. The core Christian moral intuitions remain, but the reasons that originally justified them (i.e., Christian metaphysics) are no longer viable to many of us and have been forgotten anyways.

As the scientific revolution got off the ground, and as Western intellectuals became more familiar with the traditions and customs of other cultures, belief in the Christian worldview became more untenable. Even among those who remained believers, there seemed to be some doubt that Christianity would remain the unquestionable guarantor of morality. This means that even those intellectuals who partially retained their belief in Christianity often felt some need to provide a firmer, more “rational” basis for morality. This is the origin of the secular moral philosophies of the enlightenment, most famously of Kant’s “categorical imperative” and Bentham’s utilitarianism. Although the Kantians (deontologists) and utilitarians are often at odds with each other, they both accept the fundamental tenets of slave morality (everyone must be held to the same standard, everyone counts equally). Their difference is primarily in the method of implementation (e.g., the role of duty, intention, and consequences).

We are still engaged in this process today. Public intellectuals often claim to have found a secular, rational basis for morality. Sam Harris, for example, claimed in his (2010) book The Moral Landscape to have scientifically determined moral values (by forwarding a variant of utilitarianism). Steven Pinker’s 2018 book Enlightenment Now similarly makes the case for a humanistic morality. These thinkers seem to have no indication that their moral pronouncements would make very little sense outside of a culture that has been trained in Christian moral judgements for 2,000 years. Imagine trying to convince a group of Roman aristocrats that what they really need to be doing is increasing the well-being of all sentient creatures or defending universal human rights (right after they get done raping their slave-boys, while they’re preparing to go conquer and enslave another neighboring group).

Arguments for utilitarianism, humanism, and other secular moral philosophies simply don’t work unless they are directed at people who already have the moral intuitions that underlie them. The reason those intuitions are widespread in our own culture is largely because of the influence of Christianity (Henrich, 2020; Holland, 2019; Siedentop, 2014). It’s not that these intuitions are impossible without Christianity. That’s clearly not the case, since other religions like Jainism and Buddhism have also forwarded a version of universal compassion. It’s just that the package of moral intuitions that are found among WEIRD people can be logically traced back to Christianity (Siedentop, 2014) and are highly predicted by historical exposure to Christianity (see Henrich, 2020 for empirical evidence of the dose-dependent effect of historical exposure to the Catholic church on a variety of outcomes related to moral psychology).

In sum, secular moral philosophies are post-hoc rationalizations of the moral intuitions instilled in the Western world through our 2,000-year obsession with Christianity (e.g., the “equality of souls” becomes “universal human rights”). Although the enlightenment is often presented as a radical break from the superstition and backwardness of Christianity, enlightenment values simply don’t make sense outside of a culture that has been profoundly affected by Christian moral intuitions (Henrich, 2020; Holland, 2019; Peterson, 2006; Siedentop, 2014).

The Individual Development of Utilitarianism

Why is it that when some people are exposed to utilitarian philosophy they seem to perceive it as the obviously rational approach to morality, while others find it silly or even repulsive? Even among people who share the basic intuitions of slave morality (i.e., universalism and equality) there are widely differing opinions about utilitarianism.

Sadly there is very little direct evidence about the personality traits and other individual difference factors that predispose people to utilitarianism. Nevertheless, there are a couple aspects of utilitarianism that lend themselves to a plausible (and testable) hypothesis about the kind of people who will tend to find utilitarianism attractive. In this section I will briefly review the evidence for two claims:

1) Moral intuitions are heritable (i.e., the differences between people have a genetic component).

2) The consequentialism and systemization inherent to utilitarianism would be particularly attractive to people high in autistic-like traits, which is a highly heritable individual difference factor.

The Heritability of Moral Values

Behavioral genetics is a field of study which uses a variety of methods to estimate the heritability of behavioral and psychological traits. Heritability is a concept that is often misunderstood. It does not refer to the percentage of a trait’s development that is genetically determined. For example, whether or not you are born with a nose is pretty much 100% determined by your genes, but the heritability of having a nose is zero. Why is the heritability zero? Because all normally developing humans have a nose and heritability is determined by the causes of variance in a trait. If there is no variance in a trait, there is no heritability. It’s also important to note that heritability is concerned with differences between individuals within a population and thus heritability tells us little about the causes of differences between populations (e.g., differences in moral intuitions between the people in the United States and China).

Twin studies are the most common method for estimating heritability in humans. In a typical twin study, the differences between identical twins are compared to the differences between non-identical twins and some simple math allows you to estimate the heritability of the measured traits. Other methodologies (adoption studies, pedigree studies, etc.) tend to produce results that are comparable to twin studies. Recently, technological advances have allowed scientists to directly observe the correlation between genetic variants and behavioral traits with genome wide association studies (GWAS) and polygenic scores. Although these technologies are relatively new, they have largely confirmed the basic findings of behavioral genetics that were determined through twin, adoption, and pedigree studies.

The first law of behavioral genetics is that all behavioral traits are heritable. This means that some portion of the variance in all behavioral traits (e.g., personality traits) is due to genetic differences between people. That finding has been verified countless times in the past 100 years. Behavioral genetics tells us nothing, however, about the actual mechanisms involved in these behavioral differences. For example, although extraversion is clearly heritable, behavioral genetic studies cannot tell us whether the genetic component is mediated through dopamine pathways, other brain differences (e.g., the white/gray matter composition of different areas), or a combination of factors. All that behavioral genetics can do is tell us that there is a heritable component and estimate the size of that component. For most stable traits studied by psychologists, the heritable component accounts for 40-50% of the variance.

Recent studies have shown that moral intuitions have a strong heritable component (Smith & Hatemi, 2020; Zakharin & Bates, 2022). Zakharin and Bates (2022) found a heritability of 49% and 66% for the “individualizing” and “binding” domains of morality, respectively (these domains are based on Jonathan Haidt’s moral foundations theory). They also found a general factor of morality that was 40% heritable. These findings indicate that moral attitudes have a significant genetic basis.

To my knowledge, no studies have estimated the heritability of people’s attitudes about moral philosophies. We do not know the heritability of utilitarian or deontological moral reasoning. But if we accept the first law of behavioral genetics (which is called a law because of how reliable it is), then we can surmise that the propensity to adopt utilitarianism has a heritable component. Like most other traits, that heritable component probably accounts for 30-60% of the variance. My own scientific research focuses on the diametric model of autism and psychosis (Andersen, 2022; Andersen, Miller, & Vervaeke, 2022). I study a continuum of individual differences referred to as the autism-schizotypy continuum. This continuum has a cluster of traits known as “autistic-like traits” on one side and a cluster of traits associated with “positive schizotypy” on the other. Although twin studies haven’t been performed on these traits in non-clinical populations, the heritability of autism and psychosis spectrum conditions is extremely high at around 80% (Del Giudice, 2018). Here I will argue that some characteristics associated with autism and autistic-like traits would predispose to finding utilitarianism attractive.

The Autism of Utilitarianism

In this section I am going to use the term “autism” very broadly. When many people think of autism, they think of severe autism which is often accompanied by intellectual disabilities. Here I am mainly referring to high-functioning autism or to people who are high in autistic-like traits but wouldn’t qualify for a diagnosis. Many people with high-functioning autism or high levels of autistic-like traits are smart and successful, with no obvious signs of psychopathology. Although I will use the term “autism” in this section for convenience, I am not implying that utilitarianism is associated with psychopathology.

It is no coincidence that the founding father of utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham, was obviously diagnosable with high-functioning autism (Lucas & Sheeran, 2006). My own scientific research focuses on autism and in many cases I think that retrospective diagnoses are unwarranted. Some authors (e.g., Badcock, 2019) seem to assume that anyone who was introverted and smart must have been autistic, but this is not the case. Nietzsche, for example, was introverted and smart but was clearly not autistic (e.g., the idea that Nietzsche suffered from a “theory of mind” deficit is laughable; he is considered by many to be the greatest intuitive psychologist of all time). With Bentham, however, there is little room for doubt. Those who knew him well left us with descriptions of his personality and personal life that in some cases are virtually indistinguishable from a general description of high-functioning autism. John Stuart Mill, for example, described Bentham’s unusual inability to understand other people:

In many of the most natural and strongest feelings of human nature he had no sympathy; from many of its graver experiences he was altogether cut off; and the faculty by which one mind understands a mind different from itself, and throws itself into the feelings of that other mind, was denied him by his deficiency of Imagination. (quoted from Lucas & Sheeran, 2006, p. 7)

Knowing so little of human feelings, he knew still less of the influences by which those feelings are formed: all the more subtle workings both of the mind upon itself, and of external things upon the mind, escaped him. (ibid, p. 9)

It should be kept in mind that these quotes come from someone who admired Bentham and was positively predisposed towards him. “The faculty by which one mind understands another mind” is typically called theory of mind in the scientific literature and is usually considered the principal deficit associated with autism. Bentham’s autism is not unrelated to his utilitarianism. Below I will review evidence that the consequentialism and systemization of utilitarianism would be especially appealing to people with autistic-like traits.

Consequentialism

Most people naturally take intentions into account when making moral judgements. As Henrich (2020) points out, this is especially true of WEIRD people. For most of us it is obvious that a murder is a greater moral crime than an accidental killing. By contrast, utilitarianism says that the morality of an action is determined by its consequences and not by the intentions behind the act. The consequentialism of utilitarianism therefore seems intuitively wrong to many people. People with autism, on the other hand, tend to be natural consequentialists. It’s not that people with autism never take intentions into account when making moral judgements. It’s just that they are less likely to do so than neurotypical people. Dempsey and colleagues (2019) thoroughly review the evidence for this so I won’t review it in detail here. While this literature needs some meta-analyses and larger sample studies (to get a better idea of the size and consistency of the effect), the overall pattern is clear: children and adults with autism do not weigh intentions as highly as neurotypicals when making moral judgements. They tend to give more weight to outcomes. Thus, people with autism tend to be natural consequentialists.

Systemization

The other aspect of utilitarianism that would be appealing to people high in autistic-like traits is its systemization. Consider the following excerpt from a 2012 blog post by Sam Bankman-Fried in which he makes the case for classical utilitarianism:

Are happiness and pain calculated separately for each person, or first added together? I.e.: say p, at a given point, is feeling 10 utils of happiness and 20 utlils of pain, and say k=2. Should you be calculating h(p = 10-20*2=-30, or h(p) = h(10-20) = k*(-10)=-20? The problem with the first version is that it is not going to be linear in how you view an individual's emotions… (Bankman-Fried, 2012)

I’m not trying to use the now-disgraced Sam Bankman-Fried as a punching bag for utilitarianism. I came across this excerpt because Erik Hoel posted the link on Twitter and it serves to make my point. Utilitarianism allows you to treat moral decisions like a math problem. People high in autistic-like traits tend to be systemizers (Baron-Cohen et al., 2009). They have a talent and interest for working with lawful systems. This can include systems like computer programming languages, most of mathematics, and most of physics and chemistry.