Order, Chaos, Relevance Realization, and Mythology

On the relation between John Vervaeke's relevance realization and Jordan Peterson's Maps of Meaning

*Note: This post is a little longer and the discussion is a little more technical, but I think it will be worth it for how it all comes together at the end.

Self-organized criticality

In the late 1980s and 90s, the physicist Per Bak was trying to solve the problem of complexity. The problem can be stated simply. The laws of physics are relatively simple and deterministic. You can write them all down on a single sheet of paper. Given these relatively simple, deterministic laws, why is the universe so interesting? If the laws of physics are so simple, why is everything so complex?

In his 1996 book How Nature Works: The Science of Self-Organized Criticality, Bak put forward his theory. He reasoned that complexity must emerge at the border between order and chaos. A crystal is an example of an ordered system. A crystal is not complex because if you know what one part of the system looks like, then you know what the whole thing looks like. That means an infinitely large crystal can be precisely described with very little information. That’s not complexity. A gas is a chaotic system (keeping in mind that I am not using ‘chaos’ in the technical mathematical sense here). A gas is also not complex. Even though a gas does not have the regularity of a crystal, it is still uniform throughout its entire structure. It looks the same everywhere, and therefore is not complex.

Bak reasoned that complexity must emerge at the narrow window between too much order and too much chaos. This narrow window is referred to as the critical state or just criticality. The question, for Bak, was how systems in nature could get to this narrow window without any tuning from an outside agent. We can fine-tune a system to criticality by, for example, precisely adjusting the temperature or other variables. But there is no external agent fine-tuning systems in nature. They must achieve criticality from the bottom-up, through the interactions of the parts of the system and their environment. This is the origin of the term self-organized criticality. Systems in nature self-organize to the narrow window between order and chaos, which is where they become more complex.

Bak created some toy models to show how self-organized criticality could occur, the most famous of which is called the sand-pile model. In this model, sand is added to a pile very slowly, one grain at a time. Eventually, a single grain will be enough to cause an avalanche. The avalanches occur in various sizes. What was interesting about this is that the avalanches reliably occur in a power-law distribution (Jordan Peterson usually refers to this as a Pareto distribution), which means that there are many small avalanches and only a few very large ones. This “power-law distribution of avalanches” would come to serve as the primary marker of self-organized criticality in nature. For example, earthquakes and solar flares both occur in power-law distributions, with frequent small ones and only very rare large ones.

Bak’s theory eventually failed as a general explanation of complexity — not because it was wrong per se, but because it was incomplete. There is more to the story than Bak understood. A 2018 PNAS paper entitled “The Physical Foundations of Biological Complexity” puts forward a more complete theory, but I will have to save discussion of that paper for another time.

Despite its failure as a general theory of complexity, self-organized criticality has become an important concept within biology, neuroscience, and cognitive science. Theoretical work indicates that biological systems function optimally at the border between order and chaos because being at this narrow window facilitates optimal learning and information flow. Empirical research has found signatures of criticality in systems such as flocks of birds, genetic regulatory systems, and most importantly the brain.

Because of empirical and theoretical work showing the importance of criticality for brain functioning, self-organized criticality is becoming an increasingly important concept within neuroscience and cognitive science. For example, there is empirical and theoretical work making the case that consciousness emerges at the narrow window between order and chaos in the brain. The literature relating consciousness to criticality is extremely interesting, and I will make an entire post about it later. What I want to focus on in this post are the relations between self-organized criticality, John Vervaeke’s theory of relevance realization, and the cognitive science of insight. After looking at those relations, we will see how all of that relates to Jordan Peterson’s first book Maps of Meaning.

Relevance Realization

John Vervaeke is a collaborator of mine (we just had our first paper together with Mark Miller accepted for publication) and the director of the cognitive science program at the University of Toronto. He has a great series of YouTube videos called Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, which I highly recommend. John’s academic work focuses on his theory of relevance realization, which is a theory of how organisms solve the very difficult problem of intelligently ignoring irrelevant aspects of the world and zeroing in on the relevant aspects. Although I can’t go into too much detail about relevance realization in this post, John believes (as do I) that relevance realization is a key idea for responding to the meaning crisis. In two 2013 chapters by John Vervaeke and Leo Ferraro, they argue that self-organized criticality is the mechanism by which relevance realization is instantiated in the brain:

With its self‐organizing criticality the brain engages in a kind of on‐going opponent processing between integration and differentiation of information processing. This means that the brain is constantly complexifying (simultaneously integrating as a system while [differentiating] its component parts) its processing as a way of continually adapting to a dynamically complex environment[…] The brain is thus constantly transcending itself in its ability to realize relevant information. (Vervaeke & Ferraro, 2013 p. 11)

We can therefore say that relevance realization (and the complexification associated with it) occurs at the narrow window between order and chaos. This accords with Vervaeke and Ferraro’s discussion of network theory, in which they argue that relevance realization is best achieved in the brain by small-world networks, which are intermediate to regular networks (too much order) and random networks (too much chaos). See below for a visual demonstration of these kinds of networks.

An important aspect of relevance realization is the capacity for insight. An insight is what happens when we have an ‘aha’ moment in relation to a problem we’ve been thinking about. In contrast to methodical, deliberative thinking, insights occur suddenly and often occur when we aren’t even actively thinking about the problem. As John Vervaeke and others have argued, insights involve a frame-shift. In order to deal with combinatorially explosive problems, we must put a frame around them that constrains the kinds of solutions that seem viable to us. An insight involves letting go of a previous way that we were framing the problem (which has been rendered dysfunctional or non-optimal for whatever reason) and adopting a new, more functional frame that allows us to solve whatever problem we are engaged with more effectively. This works because the previous frame has treated something important as irrelevant and the new frame brings the important information into the scope of relevance.

The self-organization of insight

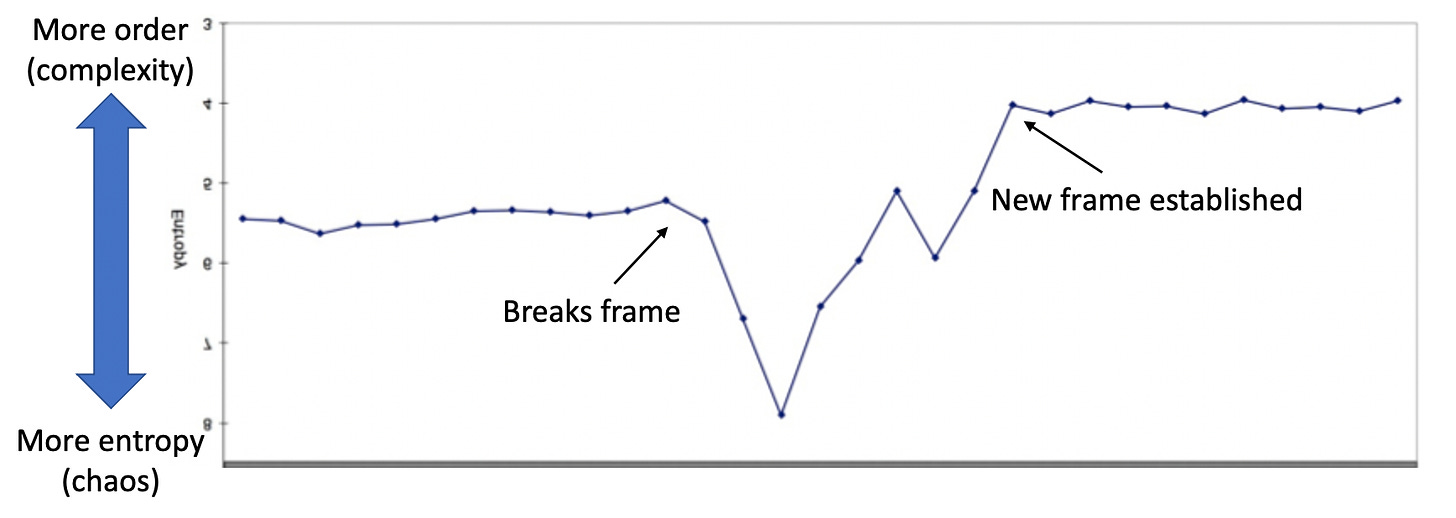

Given that insight is related to relevance realization, we might expect there to be some arguments in the literature suggesting that insight is also related to self-organized criticality. This is, in fact, what was argued by Stephen & Dixon in their 2009 paper entitled “The Self-Organization of Insight: Entropy and Power Laws in Problem Solving”. They argue that insights display the key signature of self-organized criticality, i.e., power-law distributions, and show how insights help a cognitive system to offload entropy by becoming more cognitively complex. The implication of their work is that insight is a self-organized critical phenomenon, meaning that it occurs at the border between order and chaos.

Stephen and Dixon (2009) present evidence that when somebody breaks frame (i.e., realizes that the way they are framing the problem is non-optimal), there is an increase in behavioral entropy. For our purposes, entropy can be considered a mathematical measure of disorder or chaos (in reality it’s a little more complicated than that). This means that when somebody breaks frame, there is an increase in behavioral disorder or chaos. When that person establishes a new frame, however, there is a decrease in entropy such that there is even less entropy than there was before the insight. This means that when the insight occurs there is a re-emergence into a higher form of order. The figure below is adapted from Stephen and Dixon (2009) and is meant to convey what this process looks like. I inverted the figure and added some text to make it more understandable.

So we see that the person starts out with a moderate level of entropy. When they break frame, there is a “descent into chaos” (i.e., a temporary increase in entropy). When they establish a new frame, they re-emerge from this state of high entropy into a new stable state in which there is even less entropy than before. We can summarize this process like this:

There is a relatively stable way that the person is framing the world.

For whatever reason (whether because of novel sensory input or their own internal dynamics), the person realizes that their current frame is dysfunctional or non-optimal.

The person breaks their current frame, causing an increase in behavioral entropy.

The person adopts a new, more functional frame (this is the ‘aha’ moment), causing a decrease in behavioral entropy such that there is even less entropy than before the insight.

That is the basic structure of an insight, which emerges at the border between order and chaos and is a key aspect of relevance realization.

Maps of Meaning

This brings me to the point of this post. What I want to argue now is that this entire discussion was foreshadowed by Jordan Peterson in his first book Maps of Meaning. In that book he argued that mythological narratives have converged on a general pattern, which he refers to as the meta-mythology. The meta-mythology represents the process that updates individuals and cultures in the face of existential anomalies. The meta-mythology has characteristics indicating it is essentially the same as the process I have described above in this post. These include the facts that: a) the meta-mythology occurs at the border between order and chaos, b) it has the same basic structure as an insight, and c) the meta-mythology is the process by which relevance realization occurs. This overlap is quite interesting since it occurred independently from all of the literatures discussed above. Nowhere in Maps of Meaning or in his class lectures does Jordan Peterson refer to the science of self-organized criticality (which was not well-known at the time he was writing his book), the self-organization of insight (a literature that did not exist when he was writing), or John Vervaeke’s theory of relevance realization (which also didn’t exist at the time Jordan was writing). I will now argue that Jordan Peterson’s theory from Maps of Meaning overlaps with all of these literatures.

a. The meta-mythology occurs at the border between order and chaos

There are a variety of quotes in Maps of Meaning indicating that the meta-mythology occurs at the border between order and chaos. For example, on p. 281 Peterson says that the mythological hero is a narrative representation of the meta-mythology. He says on p. 244 that the hero “stands on the border between order and chaos…”.

Peterson also discusses Chinese Taoist philosophy at length. Peterson argues that the Tao (which can be translated as “the way”) exists at the “razor’s edge” between order and chaos. The meta-mythology is also referred to as “the way”, indicating that it also exists at the border between order and chaos.

In sum, Peterson suggests throughout the book that the right place to be is at the border between order and chaos and that the meta-mythology characterizes what happens when one is at that border.

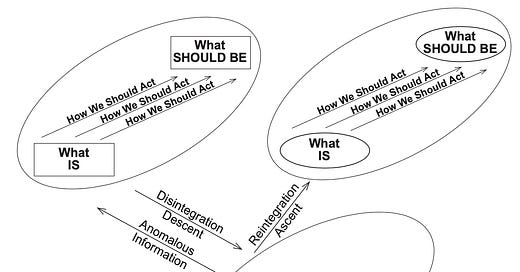

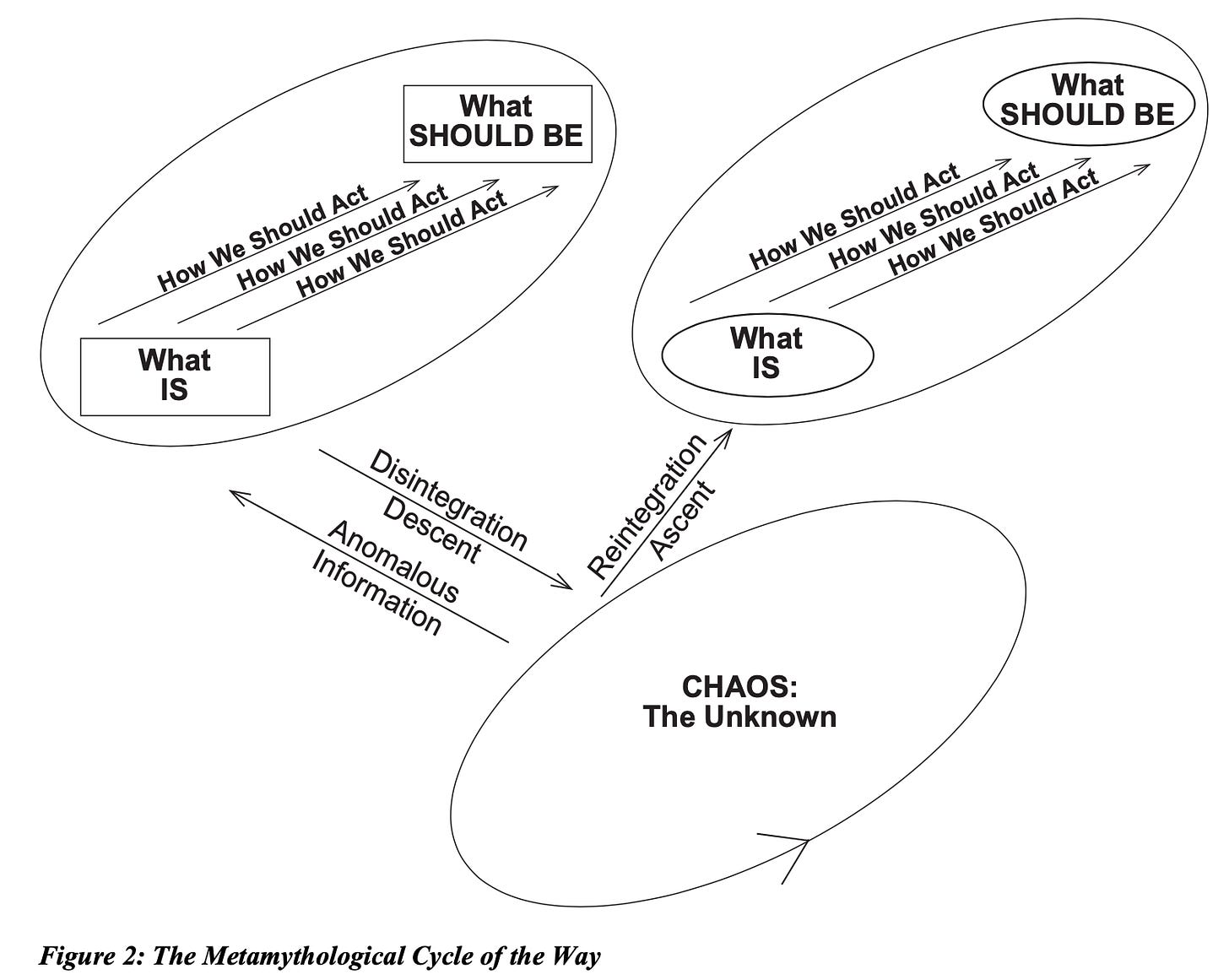

b. The meta-mythology has the same structure as an insight

The above figure is from Maps of Meaning and depicts the meta-mythology. Compare this figure to the previous figure showing the structure of an insight. The meta-mythology starts off with a particular way that we are framing the world (which Peterson refers to as a story rather than a frame). There is an anomaly of some kind that disrupts that story. As a result of the anomaly, there is a disintegration of the story (equivalent to breaking frame) and a consequent descent into chaos. If the process is successful, this is followed by a reintegration and ascent into a higher form of order (i.e., a new story that takes into account the anomaly that disrupted the previous story).

The outlines of this process are clearly the same as the structure of an insight, although the meta-mythology is more generalized because it applies not only to individuals but to groups of individuals (who have shared stories that must occasionally be re-structured) as well. To summarize the meta-mythology using the outlines of a typical hero story:

There is an initial period of relative stability (e.g., the pre-adventure paradisal state)

There is some anomaly that disrupts that stability (e.g., the call to adventure)

There is a descent into chaos (e.g., the adventure)

There is a re-emergence into a higher form of order (e.g., the post-adventure re-establishment of paradise).

For example, in Star Wars (the original trilogy), we see this pattern play out with Luke:

He is initially living in relative harmony with his aunt and uncle.

His aunt and uncle are killed and he is recruited into helping the rebellion against the empire.

He is involved in battles, rescue missions, Jedi training, etc.

He defeats the empire and helps to re-establish the Jedi order and bring peace to the galaxy.

Of course, George Lucas was explicitly influenced by Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces, so it’s no coincidence that Luke’s journey lines up so nicely with the meta-mythology. I could do the same thing, however, with other cultural phenomena, including Harry Potter and The Lion King. Stories that pull off this pattern correctly often resonate deeply with many people.

c. The meta-mythology is relevance realization

When we engage in the process characterized by the meta-mythology, what we are primarily doing according to Peterson is determining the motivational relevance of the anomaly that disrupted our previous story/frame. There are a variety of quotes in Maps of Meaning that demonstrate this, which you can find by simply searching for the word “relevance” in the PDF of the book. Here is one of them:

Exploratory behavior allows for classification of the general and (a priori) motivationally-significant unexpected into specified and determinate domains of motivational relevance. In the case of something with actual (post-investigation) significance, relevance means context-specific punishment or satisfaction, or their putatively “second-order” equivalents: threat or promise (as something threatening implies punishment, as something promising implies satisfaction). This is categorization, it should be noted, in accordance with implication for motor output, or behavior, rather than with regards to sensory (or, formalized, objective) property. (p. 53)

In other words, the process of exploration and update (i.e., the meta-mythology) is the process by which we determine the motivational relevance of novel stimuli. To put it simply, the meta-mythology is relevance realization, described in terms of a narrative and phenomenological structure rather than in terms of modern cognitive science. To relate this back to the initial discussion on self-organized criticality, the meta-mythology represents the pattern by which we self-organize to the narrow window between order and chaos, where we engage in the process by which we become more complex.

Conclusion

John Vervaeke has argued that relevance realization is an important concept for responding to the meaning crisis. Jordan Peterson is clearly dealing with issues of meaning as well. Connecting their work is important, to my mind, because while John Vervaeke has made great progress in working out the technical details of this process, Jordan Peterson has done something equally important by connecting it to our ancient traditions. As Peterson argued in Maps of Meaning, we are deeply historical creatures. Our evolutionary, cultural, and personal histories live in us and through us. To be unmoored from our past is to be unmoored from the traditions that have successfully guided our ancestors for millennia (that success is demonstrated by the fact that we are alive, meaning that we are the descendants of people who successfully survived and reproduced).

The modern mechanistic worldview is nihilistic in part because it represents a radical departure from (and denial of) everything that has been believed up to this point. The modernist viewpoint generally regards mythological narratives and the worldview they support as nothing but superstitious bullshit, which at least implicitly means that most of our ancestors were suckers who built their civilizations atop meaningless lies (this idea is quickly becoming untenable in light of the emerging science of cultural evolution; see also my recent post on supernatural beliefs).

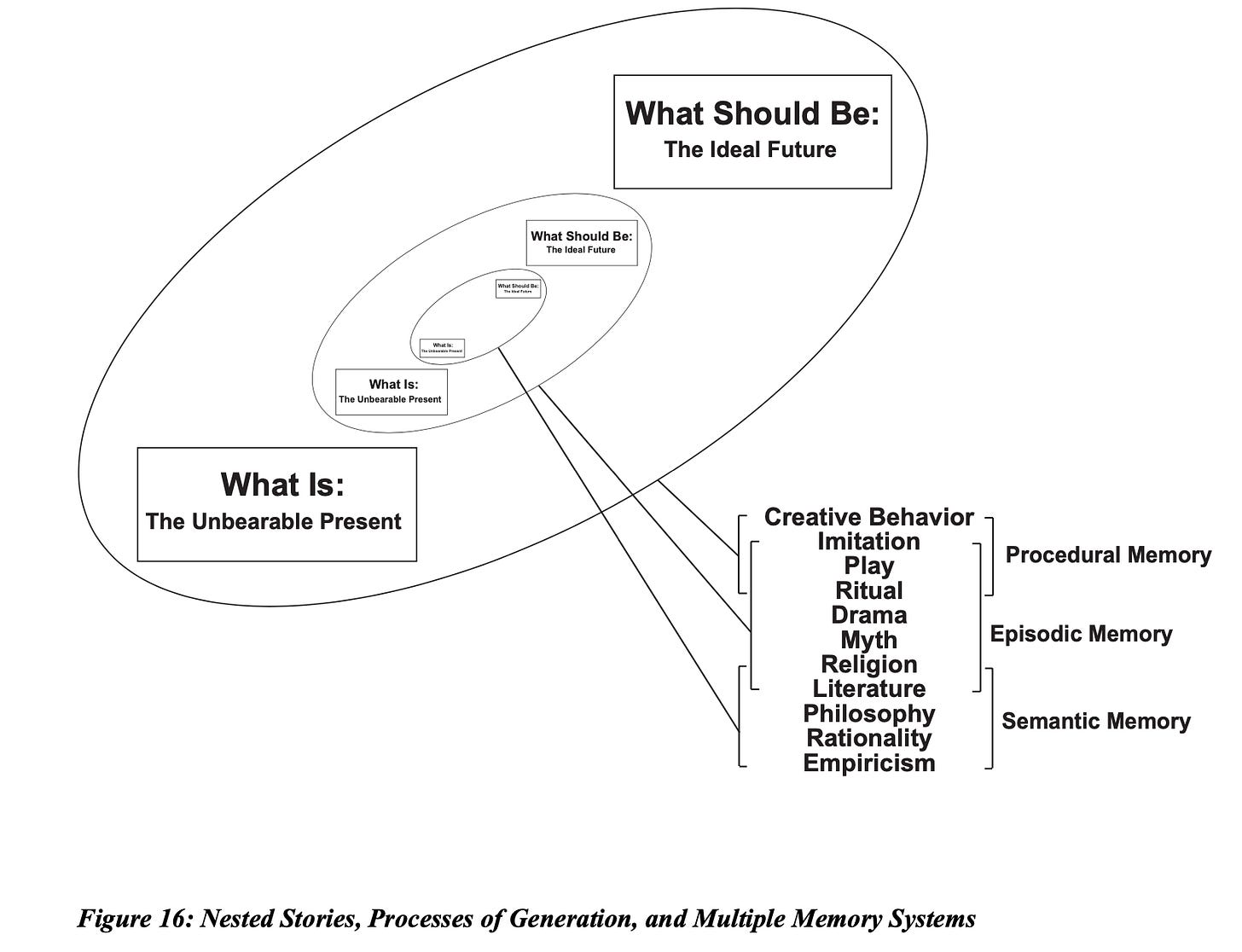

The new worldview that is emerging no longer represents such a radical departure from our ancestors. By showing that this process (i.e., the meta-mythology, relevance realization) was at least implicit in the mythological narratives that served to organize our ancestors’ civilizations, we thereby show that we are part of a long lineage of people who have been engaged in the project of discovering and articulating how to live properly. This does not mean that we must be beholden to traditional beliefs or ways of life, which is clearly not tenable given a rapidly changing world. It does mean, however, that we can see ourselves as part of a living tradition rather than looking at our ancestors with nothing but contempt (an attitude that seems to be fashionable these days, as demonstrated by Douglas Murray in his recent book The War on the West). The bottom right-hand corner in the figure below from Maps of Meaning is meant to represent a process of abstraction by which we continually become more clear about the pattern underlying admirable or optimal behavior.

First we imitate the pattern underlying admirable behaviors, then we encode that pattern into rituals, then into narratives, then into philosophical argumentation, then, finally, we gain an empirical/scientific understanding of it. In this way: “The image of the hero, step by step, becomes ever clearer, and ever more broadly applicable.” (Peterson, 1999 p. 149)

In Maps of Meaning, Jordan Peterson made a great deal of progress on making this worldview fully scientific by connecting mythological, literary, and philosophical illustrations of the meta-mythology to the best scientific theories that he had available to him at the time (mainly from cybernetics and neuroscience). That project is not complete, but Maps of Meaning laid a solid foundation for it. John Vervaeke’s work (especially his YouTube series) has exposed me to a number of ideas that have helped to further that project. I suspect that I’ll be spending the rest of my life trying to finish it. That is my response to the meaning crisis.

This is amazing Brett! I think the proposal that meta-mythological processes are the relevance realization of collective intelligence working in distributed cognition is bang on. Your final schema is also very helpful. You are quickly becoming the master of making these kinds of insightful connections. Thank you.

Hi Brett, the work I've been doing independently as a Story Editor for the past thirty years and as the creator of the Story Grid Methodology converges with your tightly constructed arguments here. The Cartesian grids I generate, which map the energy/information/pattern/meaning fluctuations of Story, using my methodology mirror the grids you feature from Stephen and Dixon. My work converges with John's work too (Story Grid will be publishing a two-volume companion book series to support Awakening from the Meaning Crisis next year) as well as Jordan Peterson's Maps of Meaning. I'd also cite The Immanent Metaphysics by Forrest Landry as the third pillar of influence on the discovery and explication of the SG Method. While Story Grid is a practical methodology, meaning Story Grid is a teaching platform to enable aspiring writers and editors to conform to what you are referring to as the Meta-Mythological process (I call it Hero's Journey 2.0) as described by Peterson, the underlying foundations are exactly as you explain here. Just wanted to let you know that I believe this is extraordinary work and absolutely essential to enable thoughtful and timely responses to this building global Kairos using the power of story to guide us. Thank you. Shawn Coyne