The Biological Functions of Dream and Myth

Myth is the collective dream and dream the personalized myth. A comment on Erik Hoel’s recent theory of dreams.

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell said that “Dream is the personalized myth, myth the depersonalized dream…”. A recent theory from neuroscientist Erik Hoel about the biological function of dreams supports this connection. In this post I will argue that the mythological narratives by which we have organized our societies act as a kind of collective dream.

Erik Hoel’s 2021 paper is entitled “The overfitted brain: Dreams evolved to assist generalization”. Hoel argued that the phenomenological characteristics of dreams can tell us something about their function. Dreams, he argues, function to help us avoid overfitting our cognitive models of the world, thereby assisting in the generalization of learning. I’ll explain what that means below. Importantly, the three phenomenological characteristics of dreams that he points out are also characteristics of mythological narratives. Could it be that mythological narratives also help with generalization? I think so, and I will argue that this idea was implicit in Jordan Peterson’s first book Maps of Meaning.

Overfitting and the problem of generalization

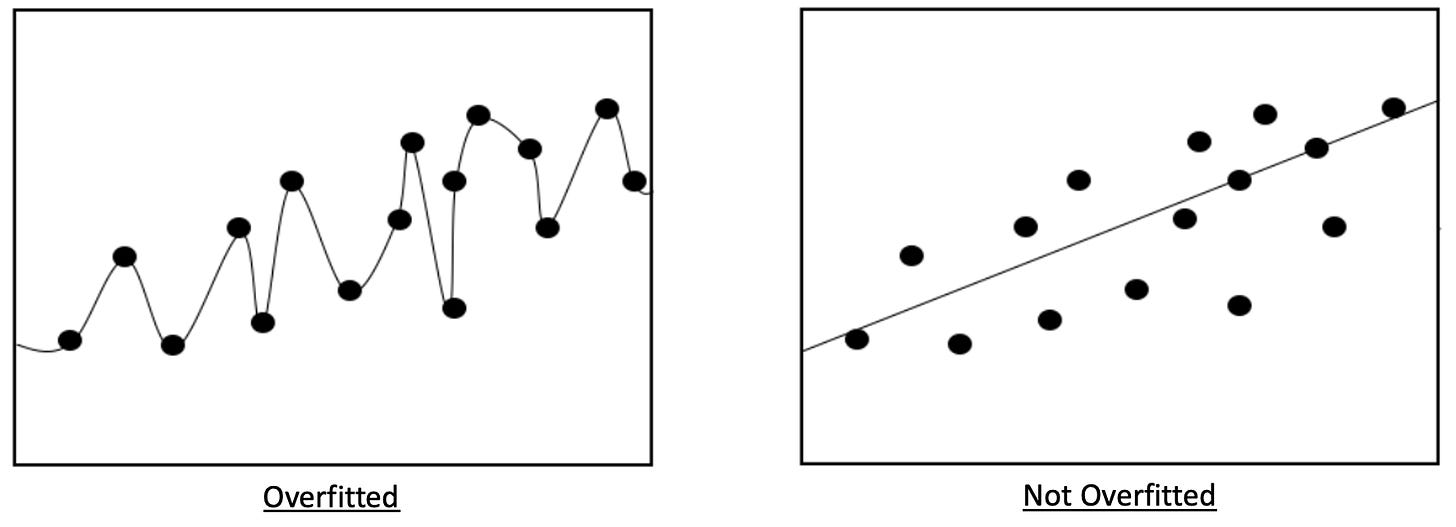

Every system that can learn — both organic and inorganic — faces a similar problem. How can that system take what it has learned in a particular situation and generalize that learning to many other situations, none of which will be precisely the same as the situation in which the learning occurred? This is a big problem in data analysis, where overfitting statistical models to the data is relatively common. Overfitting is what occurs when we try to fit our model too precisely to the data. If we try to incorporate every little deviation in the data into our model, we will likely create a model that doesn’t generalize very well. That’s because a lot of that deviation is noise, or unrepeatable measurement error. By fitting our model too precisely to the data, we will inevitably incorporate noise into our model, making it overfitted. The figure below shows the difference between an overfitted model and a model that is properly fitted to the data.

The overfitted model on the left is attempting to take into account every little deviation in the data. The properly fitted model on the right ignores some of these deviations so that it can pick up on the “line of best fit”. You could say that the model on the right is picking up on the big picture while the model on the left is getting lost in the details. This means that to some extent a model must ignore the details in order to avoid overfitting.

Overfitting is not just a problem in data analysis. It is, in fact, a deep epistemological problem that faces any system capable of learning, including us. For example, a prominent theory argues that autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are primarily caused by a perceptual difference that causes people to overfit their cognitive models of the world. According to this theory, the strengths associated with autism, including systemizing and rote memorization, are due to the highly precise nature of their perceptual system. But the weaknesses, including those associated with social interactions, are also due to failures of generalization caused by this highly precise perceptual style. As Sander Van de Cruys and colleagues (2014) put it:

[People with ASD] often excel in rigid, exact associations (rote learning). Here, their overfitted predictions serve them perfectly well, precisely because they suffer less from interference from similar instances. They seem to trade off the ability to generalize with a more accurate memory. Hence[…] the core processing deficits in ASD become most evident when some disregard for details and some generalization are needed. Generalized inferences are required in situations where exact matches are not present, which is the rule rather than the exception in natural situations, especially those involving social interactions. (p. 652)

As can be seen in ASD, there are serious consequences if we fail to construct generalizable cognitive models of the world. We are a species that is capable of a great deal of learning over the course of a lifetime. We must therefore find a way to make sure that what we learn can be generalized to novel situations. In his 2021 paper, Erik Hoel argues that our capacity for dreaming helps us to construct more generalizable cognitive models.

Dreams help to avoid overfitting

Hoel makes his case by pointing to three phenomenological properties of dreams. These are:

1. “First, the sparseness of dreams in that they are generally less vivid than waking life in that they contain less sensory and conceptual information (i.e., less detail). This lack of detail in dreams is universal, and examples include the blurring of text causing an impossibility of reading, using phones, or calculations.”

2. “Second, the hallucinatory quality of dreams in that they are generally unusual in some way (i.e., not the simple repetition of daily events or specific memories). This includes the fact that in dreams, events and concepts often exist outside of normally strict categories (a person becomes another person, a house a spaceship, and so on).”

3. “Third, the narrative property of dreams, in that dreams in adult humans are generally sequences of events ordered such that they form a narrative, albeit a fabulist one.” (p. 3)

All of these properties, Hoel argues, reflect the function of dreams in reducing and preventing overfitting. The lack of detail in dreams is perhaps the most obvious because preventing overfitting requires ignoring the details of a situation. The unusual quality of dreams helps with generalization because we need our cognitive models to be capable of generalizing to situations that are outside of the norm. It is therefore necessary that they be capable of generalizing to unusual situations. The narrative structure of dreams helps with generalization because that is largely the purpose of a narrative. A narrative helps us to take a set of facts and order them in such a way that we can extract a big picture lesson from them. Stories usually have a “moral”, after all, which means that they are meant to convey some generalizable lesson about how to act in the world. While the “moral” of dreams is not always obvious, it is the case that they usually have a narrative structure.

The phenomenological overlap between dreams and myth

What does this have to do with mythological narratives? As Erik Hoel pointed out in a blog post, mythological narratives have these same three phenomenological properties: 1) they lack detail (e.g., we usually don’t know much about the exact personality or relationships of the characters involved), 2) they often use unusual concepts that defy normally strict categories (e.g., the world resting on the back of a turtle or people being made out of the dust of the earth), and 3) they have a narrative structure.

Could it be, then, that mythological narratives also serve to prevent overfitting and aid with generalization? Hoel thinks they do:

This hypothesized connection explains why humans find the directed dreams we call “fictions” so attractive and also reveals their purpose: they are artificial means of accomplishing the same thing naturally occurring dreams do. Just like dreams, fictions keep us from overfitting our model of the world… There is a sense in which something like the hero myth is actually more true than reality, since it offers a generalizability impossible for any true narrative to possess (Hoel, 2019).

This idea is in accordance with what Jordan Peterson wrote in Maps of Meaning. Peterson argued that over long periods of time, human beings have observed people who behave admirably and have told stories about them. We then try to extract the general pattern underlying the behavior of these admirable figures. That general pattern is encoded into a fictional story. These fictions are the “hero myths” that are found cross-culturally. These myths have a general pattern, which I discussed in a previous post. This is a pattern of action that generalizes to many different situations, thus helping us to avoid overfitting our cognitive models of the world. In this way, the hero myth serves the same function as dreams.

A return to the dream

The Christian mythos was the collective dream that guided Western civilization for 2,000 years. As John Vervaeke and colleagues pointed out in their 2017 book Zombies in the Western World, this mythos is no longer viable to many of us. It certainly no longer plays the same role at a cultural level as it once did.

If the worldview of Christianity is eclipsed by secularization, then there is no viable way to recapture its potency as a meta-meaning system. This means that we need to find alternative systems of meaning that provide similar combinations of symbolic provocation, ritual and social fluency. As it turns out, such systems are not easily recreated. You cannot breathe deeply, after all, without an adequate respiratory apparatus. Out from under the canopy, our culture is left gasping in a miasma; finding our bearings in the world, establishing our capacity for action, understanding what is expected of us―these are all Sisyphean tasks while the different arenas of life remain farraginous and uncoordinated to the eyes of the agents who navigate them. (Vervaeke et al., 2017 p. 47)

As Vervaeke and colleagues argue, there is no going back. We cannot recapture Christianity (at least not in its current form) as a meta-meaning system that will be viable to the culture at large. What, then, do we do? I suspect that we must find a way to make conscious and explicit that which was unconscious and implicit in Christianity. This, it seems, was what Jordan Peterson was trying to accomplish in Maps of Meaning. As he put it:

The New Testament… offers identification with the hero as the means by which the “fallen state” and the problems of group identity might both be “permanently” transcended. The New Testament has been traditionally read as a description of a historical event, which redeemed mankind, once and for all: it might more reasonably be considered the description of a process that, if enacted, could bring about the establishment of peace on earth. The problem is, however, that this process cannot yet really be said to be “consciously” – that is, explicitly – understood. Furthermore, if actually undertaken, it is extremely frightening, particularly in the initial stages. In consequence, the “imitation of Christ” – or the central culture-hero of other religious systems – tends to take the form of ritualistic “worship,” separated from other “non-religious” aspects of life. Voluntary participation in the heroic process, by contrast – which means courageous confrontation with the unknown – makes “worship” a matter of true identification. This means that the true “believer” rises above dogmatic adherence to realize the soul of the hero – to “incarnate that soul” – in every aspect of their day-to-day life. (p. 289)

How do we recapture the dream that we lost? We must come to consciously and explicitly understand the process that is implicit in the Christian (though not only Christian) narrative while aiming to enact and embody that process in our own lives. As I will discuss in a future post, enacting this process is equivalent to participating in the process of creation itself. My contention is that truly understanding this process and its ontological grounding re-enchants the world while simultaneously providing an objectively valuable ideal to aim at (both of which render the world meaningful). This new worldview represents a return to the dream from which we emerged, albeit with a greater and more differentiated understanding of it.

*Note: Thanks to John Vervaeke for pointing out Erik Hoel’s paper to me last year.

Thanks for that interesting article - My question/comment from a practical storytelling perspective would be: The christian narrative was so successful not obly because of implicit structures, but also because of the power of the Hero of that story. We all know how important the role of a hero is for identification etc.- if we cannot revitalize the christian mythos - who will be the hero in our new narrative and is not so as Jonathan Pageau out that Christ is in the end inevitable or without an alternative?

We live in a time at war with generalizations.

Without generalizations wisdom is impossible.

When someone articulates a general principle we fixate on rare exceptions.

It feels compassionate to denounce all generalizations but it's not compassionate to those who need wisdom.

And we need wisdom.

Now more than ever.

And I'm facinated by the role dreams may play in this kind of thinking.

Brett - I'd love to have a quick 30 minute convo with you on my podcast about the connection between dreams and wisdom if you're open to it. Reach out to me on Twitter if you'd be up for discussing this further and getting these ideas in front of another audience.

@jeremympryor