The Revaluation of All Values, Part 1

How Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals foreshadowed the modern fields of evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution

Part 2: Master morality and slave morality in light of cultural group selection

Part 4: An introduction to the will to power

I know my fate. One day my name will be associated with the memory of something tremendous—a crisis without equal on earth, the most profound collision of conscience, a decision that was conjured up against everything that had been believed, demanded, hallowed so far. I am no man, I am dynamite.

(Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, IV. 1)

Although it was Jordan Peterson who woke me up from my nihilistic slumber, my greatest philosophical influence has undoubtedly been Friedrich Nietzsche. My contention is that modern scientific advancements have vindicated key aspects of Nietzsche’s project (e.g., his ‘will to power’ thesis, his rejection of ‘being’ in favor of ‘becoming’, his genealogy of morals, and his sketch of human psychology). I think that Nietzsche’s mature views got many things right, even if he wasn’t always able to clearly articulate his insights.

This is the first part of a multi-essay series in which I will update Nietzsche’s project in light of modern scientific advancements. My goal is to bring Nietzsche’s philosophical project to its logical conclusion. What was that project? He called it the revaluation (or transvaluation) of all values. Writing in the late 19th century, Nietzsche believed that there was a crisis brewing in Western culture:

What I relate is the history of the next two centuries. I describe what is coming, what can no longer come differently: the advent of nihilism. This history can be related even now; for necessity itself is at work here. This future speaks even now in a hundred signs, this destiny announces itself everywhere; for this music of the future all ears are cocked even now. For some time now, our whole European culture has been moving as toward a catastrophe, with a tortured tension that is growing from decade to decade: restlessly, violently, headlong, like a river that wants to reach the end, that no longer reflects, that is afraid to reflect. (Will to Power, 2)

Our great traditions in the West, spanning back to our Greek and Jewish origins, culminated in the scientific enterprise which, along with other cultural changes, undermined the presuppositions of those very same traditions. Properly understood, nihilism (i.e., the radical rejection of all meaning and value) was the only logical conclusion:

For why has the advent of nihilism become necessary? Because the values we have had hitherto thus draw their final consequence; because nihilism represents the ultimate logical conclusion of our great values and ideals—because we must experience nihilism before we can find out what value these “values” really had.— We require, sometime, new values. (Will to Power, 4)

When Nietzsche claims that we must ‘create new values’, this is sometimes interpreted as if Nietzsche thought we could just make up whatever values we want. But Nietzsche was far more subtle than that. He understood that we have a biological and cultural heritage to contend with and so we cannot simply make up whatever values we want. This is why Nietzsche believed that the creator of new values must be somebody with the capacity to bring many different points of view to bear on the problem. The creator of new values must be able to take many different perspectives so that he can see his problem in the most general possible light:

It may be necessary for the education of a genuine philosopher that he himself has also once stood on all these steps on which his servants, the scientific laborers of philosophy, remain standing — have to remain standing. Perhaps he himself must have been critic and skeptic and dogmatist and historian and also poet and collector and traveler and solver of riddles and moralist and seer and “free spirit” and almost everything in order to pass through the whole range of human values and value feelings and to be able to see with many different eyes and consciences, from a height and into every distance, from the depths into every height, from a nook into every expanse. But all these are merely preconditions of his task: this task itself demands something different — it demands that he create values. (Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 211)

The creator of new values cannot do so on a whim. It cannot be their mere opinion. They must be educated such that they can see through the eyes of all the other great systems of value that the Western moral tradition has passed through. Nietzsche’s revaluation project is not, in that sense, unmoored from the Western moral tradition. To the contrary, it is the logical conclusion of that tradition. The Western tradition (in both its Greek and Judeo-Christian origins) culminated in the crisis of nihilism, but that is only a transition:

Now that the shabby origin of these values is becoming clear, the universe seems to have lost value, seems “meaningless”—but that is only a transitional stage. (Will to Power, 7)

Nihilism as a transitional stage is necessary because it released us (at least those of us who have experienced it) from the dogmas and assumptions that had held the Western mind captive for thousands of years. Only after we have shaken off our previous assumptions is a revaluation possible. Nietzsche believed that the scientific enterprise would eventually be put to work in alleviating modern nihilism by helping to solve what he referred to as “the problem of value”. As he put it in The Genealogy of Morals:

All the sciences have now to pave the way for the future task of the philosopher; this task being understood to mean that he must solve the problem of value, that he must fix the hierarchy of values. (I. 17)

The problem of value is essentially the problem of bridging the Humean gap between “is” and “ought”, that is, to make value judgements fully continuous with factual statements about the world. This is what Nietzsche’s will to power thesis was attempting to do. I think he actually put forward a viable solution to the problem, though as a first pass it was somewhat vague and uncertain. This is, however, the problem he was working on at the end of his philosophical career. He supposedly had plans for a book called “The Will to Power: An Attempt at a Revaluation of All Values”. These plans never came to fruition, as Nietzsche went insane in 1889 and never worked again.

My goal in this series of essays is to bring Nietzsche’s project to its logical conclusion in light of modern scientific advancements. This means that I am not just attempting to interpret Nietzsche’s views, but rather to integrate his insights with modern scientific advancements in order to advance the project that Nietzsche was working on at the end of his life. In doing so, I will rely heavily on the secondary philosophical literature about Nietzsche rather than Nietzsche’s own writings. This is because Nietzsche’s own writing is often obscure and heavily dependent on the context in which it is written. Many insightful philosophers have spent their entire careers attempting to understand and interpret Nietzsche’s writing. I would be foolish not to take advantage of their hard work.

The Will to Power

In this series of essays I will put forward an understanding of Nietzsche’s “will to power” and “revaluation of all values” in light of modern evolutionary psychology, cultural evolution, cognitive science, and complexity science.

Until recently, I was of the opinion (which I inherited from Jordan Peterson) that Nietzsche had properly formulated the problem of nihilism and had done a good job of tracing its genealogy, but that his solution to the problem wasn’t viable. Nietzsche’s “revaluation of values” consisted of concepts like the will to power and the overman which have been subject to a variety of interpretations (and misinterpretations). It’s all very confusing.

The philosopher John Richardson’s 1996 book Nietzsche’s System convinced me that Nietzsche did put forward a viable solution to the problem of nihilism. As it turns out, Nietzsche’s solution to the problem is extremely similar to the one I have been developing, which I laid out in my recent post “Intimations of a New Worldview”. Of course, Nietzsche uses a different vocabulary and different kinds of evidence than I do, but the general thrust of his argument is extremely similar.

I have a major disagreement with Richardson, however, which has to do with his tendency to downplay and regard as implausible Nietzsche’s metaphysical claims about the will to power. This is a common refrain among philosophical commentators on Nietzsche. Many commentators will say that Nietzsche had great psychological insights, but that his metaphysical claims were highly implausible. For example, philosopher Brian Leiter, in his 2014 book Nietzsche on Morality, referred to the will to power as a “crackpot metaphysics” and suggested that, as philosophers, we would be doing Nietzsche a favor by interpreting the will to power in purely psychological terms rather than as a metaphysical thesis.

Needless to say, I disagree. Nietzsche’s metaphysics of the will to power is not “crackpot”, nor is it separable from his response to nihilism. We will not be doing him any favors by downplaying it. His will to power thesis is, in fact, the crux of his mature response to the problem of nihilism (i.e., the views found in his later writings).

Regarding Nietzsche’s metaphysical claims, I will be referring mainly to philosopher Tsarina Doyle’s 2018 book Nietzsche’s Metaphysics of The Will to Power along with a 2022 dissertation by philosopher Paul Curtis entitled Nietzsche’s Will to Power: A Naturalistic Account of Metaethics Based on Evolutionary Principles and Thermodynamic Laws. These philosophers take Nietzsche’s metaphysical claims seriously and show how they are intimately tied up with Nietzsche’s project of the revaluation of all values. Paul Curtis shows how Nietzsche’s will to power thesis is connected to the modern scientific understanding of complexity in nature. Building off Curtis’ thesis, I will argue in a future essay in this series that cognitive neuroscientist Bobby Azarian, in his recent book The Romance of Reality, puts forward a set of metaphysical claims supported by the last 30 years of advancements in complexity science that are highly concordant with Nietzsche’s metaphysics of the will to power.

A Genealogy of Morals

Before we can discuss the will to power and its relation to Nietzsche’s solution to nihilism, we must first set up the problem. In this essay I will be discussing evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution as methods for uncovering the origins of our moral values.

Where did our moral values come from? Why do we have them? Whose interests do they really serve? These are the questions we will be asking from the point of view of the modern sciences of evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution.

Both Nietzsche and I are naturalists about moral values. We do not believe that moral values are somehow immune to scientific or naturalistic understandings. They are not, for example, handed down to us by a transcendent God that exists outside of nature. It is only by gaining a naturalistic understanding of where our values came from that we can judge them properly. This was the purpose of Nietzsche’s great book The Genealogy of Morals:

Under what conditions did Man invent for himself those judgements of values, "Good" and "Evil"? And what intrinsic value do they possess in themselves? Have they up to the present hindered or advanced human well-being? Are they a symptom of the distress, impoverishment, and degeneration of Human Life? Or, conversely, is it in them that is manifested the fullness, the strength, and the will of Life, its courage, its self-confidence, its future? (Nietzsche, Genealogy of Morals, Preface 3)

…we need a critique of moral values, for once the value of these values is itself to be put in question—and for this we need a knowledge of the conditions and circumstances out of which they have grown, under which they have developed and shifted. (Genealogy of Morals, Preface 6)

Despite his mistakes (which are understandable in light of the time he was writing), we will see how closely Nietzsche’s genealogy is to a modern scientific understanding of where moral values come from through the fields of evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution.

Nietzsche’s New Darwinism

In order to reconcile Nietzsche’s ideas with modern evolutionary psychology, he must first be reconciled with Darwinism more generally. This poses a slight problem, as Nietzsche made what John Richardson referred to as “a jumble of mistakes about Darwin and mistakes about biology.”

Often, Nietzsche misunderstands Darwin and attributes views to him that he didn’t actually hold, such as the idea that fitness is equivalent to physical strength. Nietzsche’s criticisms of Darwinism are often based on these kinds of misunderstandings. In his 2004 book Nietzsche’s New Darwinism, John Richardson argues that many of these disagreements and mistakes are superficial. They are easily peeled away from Nietzsche’s primary argument. Richardson argues that Nietzsche is, in fact, deeply Darwinian and that this Darwinism pervades his entire philosophy.

Although Nietzsche mentions Darwin only sporadically, and then usually to rebuke him, his thinking is deeply and pervasively Darwinian. He writes after and in the light of Darwin, in persisting awareness of the evolutionary scenario. Here, as often elsewhere, his seemingly dismissive remarks express his own sense of closeness: he sees it as his nature to repel where he most feels an affinity. (Richardson, 2004 ch. 1)

Before taking a closer look at Nietzsche’s Darwinism, we must first review some basic concepts from evolutionary biology and evolutionary psychology.

Inclusive Fitness

Ever since the modern synthesis of genetics and Darwinian evolution, evolution has been construed as being about changes in gene frequencies in a population. Genetic variants are selected based on their capacity to reproduce themselves into future generations. Besides random fluctuations (referred to as genetic drift), genetic variants can reproduce themselves into future generations in one of two ways:

By promoting the reproductive success of the organism they reside in.

By promoting the reproductive success of individuals who are statistically more likely than a random individual to contain a copy of the same genetic variant (i.e., kin/family).

Your parents and siblings have a 50% chance of having the same genetic variant as you because they share, on average, 50% of your genes. Your grandparents, half siblings, aunts, uncles, nieces, and nephews have a 25% chance. Your first cousin has a 12.5% chance, and so on.

Natural selection, therefore, does not maximize individual reproductive success. Instead, natural selection selects for adaptations that maximize an organism’s inclusive fitness. Inclusive fitness is technically defined as the sum of the contribution of an individual to its own reproductive success and its contribution to the reproductive success of other individuals, weighted by a coefficient of relatedness that summarizes the average genetic similarity between the former individual and the latter ones (Del Giudice, 2018 p. 7).

To put that in more familiar terms, we can maximize our own inclusive fitness by having lots of kids or by helping our close family members have lots of kids. Evolution hasn’t made us completely selfish, but it has made us nepotistic. In summarizing this idea, the biologist J.B.S. Haldane is reported to have jokingly said that he would lay down his life for two brothers or eight cousins (since these add up to the same coefficient of relatedness).

This is a very basic overview of inclusive fitness, but it will help us in understanding the sometimes onerous concept of “adaptation” as it is used by modern evolutionary biologists and psychologists.

Psychological Adaptations

In evolutionary biology, adaptations are defined as inherited, reliably developing characteristics of organisms that have been selected for because of their causal role in enhancing the inclusive fitness of individuals that possess them. Not all characteristics of organisms are adaptations. Some characteristics can evolve through random genetic drift or as byproducts of adaptations. As the evolutionary psychologist Marco Del Giudice put it:

While adaptations are (by definition) a product of evolution, evolution does not always produce adaptations… traits may become fixated in a population by drift, a random process by which neutral or even deleterious characteristics become more prevalent due to chance fluctuations in the frequency of traits… In addition, many traits are not adaptations in themselves but rather byproducts of other adaptations.” (Del Giudice, 2018 p. 9)

The red color of blood is an example of a byproduct. Blood functions to transport oxygen throughout the body. It uses iron atoms to accomplish this. It turns out that oxygenated iron is red in color, but the redness does not itself contribute to the adaptive function of blood. It is simply a byproduct. Differentiating between byproducts and adaptations can sometimes be difficult and is a source of many criticisms of adaptationist biology.

In this essay we will mainly be focusing on psychological adaptations. These are mental or behavioral characteristics that reliably develop and were selected for because of their positive effect on the inclusive fitness of our ancestors. It is important to understand that psychological adaptations need not be consciously understood by the organism who possesses them:

The logic of adaptation through natural selection has an important implication: as evolution proceeds, individual organisms are selected to develop and behave in ways that maximize their (expected) inclusive fitness. One does not have to assume that individuals are intentionally or consciously maximizing their fitness; they only need to function as if they were attempting to do so… (Del Giudice, 2018 p. 10; my emphasis)

This is a source of constant confusion about evolutionary psychology and related fields. Evolutionary psychologists do not believe that organisms are consciously pursuing their own inclusive fitness. Instead, we are executing adaptations that were selected for because they reliably increased inclusive fitness in the past, relative to the alternatives.

Two of the founders of evolutionary psychology, John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, make the important point that inclusive fitness is the criteria by which adaptations are selected but cannot be the actual goal of adaptations themselves (e.g., see their 2015 chapter in The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology). As they cogently argue, it is simply impossible to strive for maximizing inclusive fitness in any domain-general way. This would require a kind of unbounded rationality that is impossible even in principle because of combinatorial explosion. Instead, evolution results in relatively domain-specific adaptations that, statistically speaking, increased inclusive fitness relative to the alternatives in the past. We do not “maximize fitness” but rather “execute adaptations” which we have because they statistically increased inclusive fitness in the past.

For example, we have a sex-drive because it promoted reproductive success throughout our lineage’s evolutionary history, but the sex-drive doesn’t explicitly aim at reproductive success, as demonstrated by the fact that people are still driven to have sex when they are on birth control, after vasectomies, etc., when reproduction is impossible. The sex-drive is a prime example of a psychological adaptation that would reliably increase inclusive fitness for most of our ancestors without requiring any conscious drive to maximize fitness.

Another important point made by Cosmides and Tooby (1994) is that psychological adaptations tend to be domain-specific (meaning that each adaptation deals with a relatively narrow problem related to inclusive fitness) rather than domain-general. Purely domain-general adaptations would require an unbounded rationality that is computationally intractable due to combinatorial explosion.

These adaptations can be extremely specific. For example, there is a large body of empirical evidence demonstrating that primates have domain-specific psychological adaptations for dealing with snakes due to primates’ long history of co-evolution with snakes. The primate brain shows faster, stronger neural responses to snakes than to other stimuli. Humans have been shown to pick up on visual patterns indicating snakes more easily than other animals.

On this point, however, I think that Tooby and Cosmides often overplay their hand. Although domain-specificity is a pervasive design feature of human and animal psychology, their focus on domain-specificity leads them to overlook the extent to which many human faculties are domain-general, despite the fact that pure domain-generality is impossible. For example, Tooby & Cosmides (2015) claim that autism is due to a domain-specific deficit in social cognition, but this is clearly wrong. Autism is an extremely domain-general phenomenon (e.g., Van de Cruys et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, there is overwhelming empirical evidence that the mind contains many domain-specific psychological adaptations that correspond to different adaptive problems. See, for example, the 2015 Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology edited by David Buss for many examples of domain-specific psychological adaptations. As we will see, this picture is very similar to how Nietzsche understood the structure of the mind.

Nietzsche’s Drive Psychology

In discussing Nietzsche’s drive psychology, I will be heavily relying on the philosopher John Richardson’s trio of books about Nietzsche. Nietzsche believed that the human psyche was not a unified entity, but rather a loose collection of semi-autonomous “drives”, each of which has a particular domain of activity by which it seeks to grow its own power. Nietzsche’s “drives” are, for all intents and purposes, equivalent to the “psychological adaptations” espoused by modern evolutionary psychologists. For evolutionary psychologists, psychological adaptations:

Are domain-specific

Generally function unconsciously, and

Were selected for because of the benefits they bestowed upon a lineage in the past.

All of these are characteristics of how Nietzsche describes the drives that make up the human psyche. There is at least one difference, however, in how drives are supposed to work and how psychological adaptations are sometimes said to work. Evolutionary psychologists sometimes construe psychological adaptations as primarily reacting to incoming stimuli, while for Nietzsche drives were fundamentally proactive.

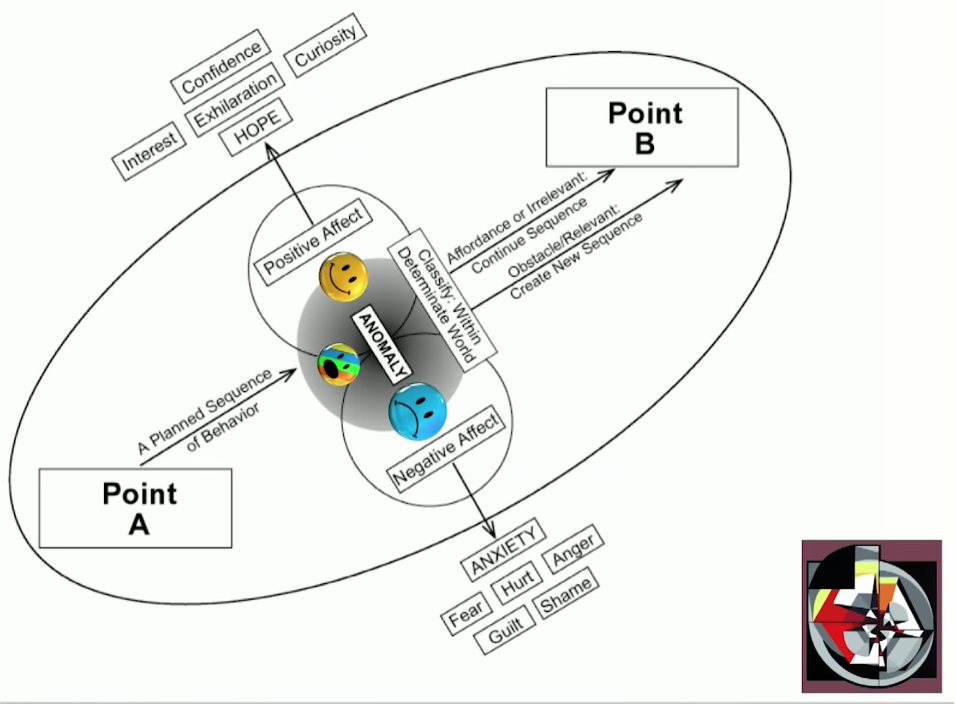

For example, the evolutionary psychologist David Buss, in his 2019 textbook on evolutionary psychology, said that “The input of an evolved psychological mechanism is transformed through decision rules or procedures into output.” He demonstrates what he means with a figure resembling the figure below.

The idea here is that a domain-specific psychological adaptation takes in a particular kind of sensory input (e.g., visual input indicating the presence of a snake), then computes some evolved decision rules about how you should act in relation to that input, which then results in a particular behavioral output.

While this simplified model can work in some circumstances, it is a poor general model of how the mind works. Organisms are not input-output machines. We don’t use if-then decision rules (behavioral outputs are much more complex than that), and psychological adaptations are fundamentally proactive rather than reactive. By proactive I mean that they tend to be goal-oriented. We proactively seek certain kinds of input and don’t just passively receive input and react to it as Buss’s model seems to suggest.

We are always actively pursuing adaptive goals, including those related to exploration/curiosity, hunger, affiliation, sex, etc. Input is not merely given to us but is largely determined by what we encounter in our active pursuit of goals. We do, of course, react to environmental stimuli/perturbations, but we largely react to things that either disrupt our goal pursuit or represent opportunities to further the pursuit of goals we already have.

We will have characteristic reactions to different kinds of input (e.g., cues indicating snakes, disease, sexual infidelity, etc.), which evolutionary psychologists have done a good job of studying. But those reactions are not really based on if-then decision rules and they are built into a psychological architecture that is fundamentally proactive. Rather than if-then decision rules, we should think of organisms as adjusting their aims towards biologically relevant targets in a quasi-Bayesian manner (which we will discuss more in a future essay in this series on predictive processing).

The figure below from Jordan Peterson’s biblical series is a better (and more complicated) representation of the basic structure of the mind.

We are always moving towards an aim of some kind (from point A to point B). We react to inputs in relation to how they affect our aims (is this input an affordance, an obstacle, or irrelevant?). Indeed, this is why Nietzsche calls them “drives”. They are not primarily reactive, but rather they drive us forward towards biologically relevant aims:

…neither the drives nor the affects, for Nietzsche, are primarily responding to external pre-existing objects. That our evaluative drives are not primarily responses to actually existent objects can be discerned from Nietzsche’s claim that such objects should be understood as either facilitators or obstacles to the drive’s aim to manifest its irreducibly particular quantum of power optimally. (Doyle, 2018 p. 153)

Objects in the world, as Tsarina Doyle points out, should be thought of as being either facilitators or obstacles in relation to our drive’s aims. Objects are classified according to their motivational relevance, or their implication for action in relation to our drives, as Jordan Peterson suggests in the figure above.

We will come back to these ideas in a future essay when I discuss predictive processing, which is a cognitive science paradigm that conceptualizes organisms as having reliably developing “adaptive priors” which are biologically relevant targets that we are predisposed to move towards in a relatively plastic manner (e.g., Badcock et al., 2019).

Fundamental Motivations

Considering that psychological adaptations (i.e., drives) are fundamentally proactive, what kinds of goals do they aim at? Evolutionary psychologists Vlad Griskevicius and Douglas Kenrick (2013) put forward a nice framework for thinking about this from an evolutionary perspective. They posit seven adaptive motivational domains:

1.Self-protection

2.Disease-avoidance

3.Affiliation

4.Status-seeking

5.Mate acquisition

6.Mate retention

7.Caring for family

I think this may leave out some important domains, (e.g., self-transcendence or self-improvement, which is different from status-seeking) but it’s still a decent list. Each of these domains will contain multiple psychological adaptations (or “drives”), so this is not meant to be an exhaustive list of human drives, only a list of some relevant categories that drives will fall under.

Drives exist because of past selection pressures

John Richardson argues that for Nietzsche, drives are the way they are because of the selective advantages they gave the organism’s ancestors:

…for Nietzsche the crucial further point is supplied by Darwin: due to natural selection, these dispositions were one and all “designed”—and fixed in the organism’s ancestral line—due to some way(s) that they served the preservation or growth of its kind… A drive is crucially the sign, then, of the selective advantages it served at the times it was formed and modified. (Richardson, 2020 p. 87)

As recognized by evolutionary psychologists, drives are the way they are because of past selection pressures rather than current ones.

Drives do not consciously aim at fitness

Drives do not aim at maximizing fitness. Rather, they flexibly seek to achieve proximate goals that would have been correlated with fitness in the past. As Richardson put it:

A drive is a behavioral disposition that is “plastic” toward its distinguishing outcome… The drive is sensitive and responsive to conditions insofar as they help or hinder its pursuit of that outcome. By contrast the drive is not thus responsive to the “imposed” end of reproductive success; [the eat-drive] does not adjust its eating in the light of what (in particular conditions) serves that success.(Richardson, 2020 p. 88)

A drive’s “ultimate” aim is inclusive fitness (i.e., reproductive success), but it achieves this through a different but related “proximate” aim (e.g., eating, sex, nepotism, disease avoidance, etc.). Neither the ultimate or proximate aim needs to be consciously available to the organism.

A community of drives

Nietzsche’s recognition of the human as being a collection of drives, each with their own (sometimes conflicting) interests leads him to a proposition that will be familiar to many evolutionary psychologists. He claims that our experience of being a unified subject is a kind of illusion:

The ‘subject’ is only a fiction; the ego [Ego] of which one speaks when one censures egoism does not exist at all. (Will to Power, 370)

The assumption of one subject is perhaps not necessary: perhaps it is just as allowable to assume a multiplicity of subjects, whose interplay and struggle lie at the basis of our thinking and of our consciousness generally? (Will to Power, 490)

This is not to say that Nietzsche totally rejects any notion of there being a ‘self’, only that we must conceptualize the self as a tentative unity of other ‘selves’ (i.e., drives, affects, habits, etc.). As individuals, we are a community rather than a unity, although there are ways that we can become more unified.

Compare Nietzsche’s views about subjectivity with what the evolutionary psychologist Robert Kurzban said in his 2010 book Why Everyone (Else) is a Hypocrite:

The modular view of the mind makes one wonder if there’s such a thing as “me” or “the self.” In the end, the mind is just a bunch of modules doing their jobs. (p. 45)

It’s easy to think that the conscious I is “in charge,” originates decisions, and, basically, is every single module. But it’s not. (p. 52)

What Kurzban calls modules, Nietzsche would call drives. As with Nietzsche, Kurzban is recognizing that the mind is a community rather than a unity so that there really is no unified “self” or “I”. I do think there is a way of understanding the “self” as a higher-level synthesis of the drives/modules, but I won’t be talking about that here.

Unconscious motivations

I want to point out one more area of overlap between Nietzsche and Robert Kurzban that follows straight-forwardly from seeing the mind as a collection of loosely unified drives or modules. Jason Weeden and Robert Kurzban coauthored a 2014 book called The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind in which they showed that people’s moral and political opinions were largely determined by self-interest. For example, people’s opinions about abortion were predicted by their own propensity for non-marital sexual encounters (i.e., their potential need for an abortion). Furthermore, those who are more likely to benefit from social safety nets (which is not entirely predicted by income) are more likely to support those policies. People’s opinions on group-based issues (e.g., affirmative action) largely depend on how they would benefit from group-based policies.

Weeden and Kurzban have convincing data showing that people’s moral/political opinions reliably (although not perfectly) track self-interest, and yet people virtually never construe their opinions on these issues as being self-interested. Instead, they construe their opinions in abstract, moralistic, “objective” terms. Moreover, people genuinely do not believe they are motivated by self-interest on these kinds of issues. They see their opinions as being due to moral/ethical concerns, etc. In other words, morality often conceals self-interested motivations, even to ourselves. In Kurzban’s terms, this is because the modules that determine our moral intuitions are different from the modules that determine how to communicate them.

Nietzsche famously holds a very similar position. For Nietzsche, people’s moral claims are often reflections of their own unconscious drives. We are more likely to adopt and promote moral norms that ultimately benefit us, but we are largely unconscious of this. In his most famous example, he argues that the weakest among us are the most likely to promote a morality primarily based on compassion because the weak are the most likely to benefit from other people’s compassion. Bernard Reginster, in his 2006 book The Affirmation of Life summarizes Nietzsche’s position:

…when the physiologically weak individual claims that compassion is good, he is in reality… pointing to the fact that a compassionate world favors the thriving of individuals of his physiological condition [although this is not necessarily his own understanding of what he is doing]. (p. 76)

These overlaps between Nietzsche’s views and Kurzban’s simply reflect the fact that certain ideas become logically obvious when you construe the mind as a collection of semi-autonomous drives (for Nietzsche) or modules (for Kurzban).

Drives and Human Values

Evolved drives are one source of human values. If the evolutionary psychologists are right, we value sex, food, friendship, family, reputation, social status, and a host of other things because valuing them served the inclusive fitness interests of our ancestors. Although Nietzsche was not privy to modern understandings of evolutionary theory or behavioral genetics, his view about drives is highly concordant with today’s evolutionary psychologists. Drives are the way they are because of how they affected the growth of lineages in the past.

Furthermore, we have drives (or psychological adaptations) that are specifically moral in nature. Evolutionary developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello, in his 2016 book A Natural History of Human Morality argues that human morality is partially determined by species-typical adaptations that lead us to value fairness, reciprocity, and social conformity because of selection pressures that affected our lineage in the distant past. These aspects of our evolved psychology are an important determinant of moral values today.

It is only, then, by studying our evolutionary history and its implications that we can gain an understanding of the origins of human values — moral or otherwise. Besides evolved drives, however, Nietzsche recognized another important source of human values. These are values that do not result from our deep evolutionary history, but rather from more recent cultural forces. John Richardson refers to this Nietzschean idea as the “social selection” of norms and values. Nietzsche’s ideas about this are very similar to the modern scientific understanding of cultural evolution.

Cultural Evolution and Social Selection

Apart from the naturally selected drives, Nietzsche recognized a second source of human values in cultural evolution (which John Richardson refers to as social selection). Cultural evolution is a scientific field that treats cultural changes as being analogous to Darwinian evolution. Cultural evolutionist Joseph Henrich, in his 2016 book The Secret to Our Success, suggests that the capacity for cumulative cultural evolution is largely what sets humans apart from other animals:

The key to understanding how humans evolved and why we are so different from other animals is to recognize that we are a cultural species. Probably over a million years ago, members of our evolutionary lineage began learning from each other in such a way that culture became cumulative. That is, hunting practices, tool-making skills, tracking know-how, and edible-plant knowledge began to improve and aggregate—by learning from others—so that one generation could build on and hone the skills and know-how gleaned from the previous generation. After several generations, this process produced a sufficiently large and complex toolkit of practices and techniques that individuals, relying only on their own ingenuity and personal experience, could not get anywhere close to figuring out over their lifetime. (p. 3)

In order to understand the origins of culturally evolved values, we must first gain a basic understanding of the processes by which cumulative cultural evolution occurs. One of the most important of these processes is referred to by scientists as “cultural ratcheting”. As we will see, Nietzsche intuitively picked up on the contours of this process long before we began to study it scientifically.

Cultural Ratcheting

Michael Tomasello (the developmental psychologist mentioned earlier), in his 1999 book The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition, describes the “ratcheting” process by which cumulative cultural evolution occurs. This process requires, in the first place, a kind of blind imitation, in which people imitate their cultural models without any rational explanation for their actions. This is referred to in the literature as “overimitation”. Chimpanzees don’t do this. If you show a chimpanzee how to perform a certain task, they will only imitate actions that are causally relevant to the task at hand. Human beings will imitate even irrelevant actions. This may seem irrational, but it is absolutely necessary for the cultural ratcheting process.

This blind, seemingly irrational imitation is necessary for cultural ratcheting because individuals aren’t smart enough (or don’t have access to enough information) to figure out how or why many culturally evolved processes works. Joseph Henrich (2016) gives an example of how blind imitation like this is adaptive.

Some hunter-gatherers eat a plant called manioc that is toxic in its natural form and therefore requires processing. Sometimes the toxin takes weeks or even years to have an effect, meaning that it’s almost impossible to identify the source of the toxicity. Nevertheless, groups that eat these plants engage in complex processes that detoxify them.

As Henrich points out, the individuals who engage in this process often have no idea what they are doing from a mechanistic, causal perspective. They don’t really understand that they are detoxifying the plant and they definitely don’t understand why (from a mechanistic perspective) the process they engage in makes the plant safer to eat.

This is because the detoxification process did not result from rational contemplation or causal analysis. Rather, it evolved through a ratcheting process that is causally opaque to those who engage in it. This causal opacity is common with culturally evolved technologies and institutions. We often engage in adaptive practices that are the products of cultural evolution without having a causal understanding of why the practice is functional.

Many human institutions are like this: we didn’t invent them so much as evolve them, we don’t really know how or why they work, and they are preserved through blind imitation rather than rational reflection. As Joseph Henrich put it in his 2016 book The Secret of Our Success:

The point here is that cultural evolution is often much smarter than we are. Operating over generations as individuals unconsciously attend to and learn from more successful, prestigious, and healthier members of their communities, this evolutionary process generates cultural adaptations. Though these complex repertoires appear well designed to meet local challenges, they are not primarily the products of individuals applying causal models, rational thinking, or cost-benefit analyses. Often, most or all of the people skilled in deploying such adaptive practices do not understand how or why they work, or even that they “do” anything at all. Such complex adaptations can emerge precisely because natural selection has favored individuals who often place their faith in cultural inheritance—in the accumulated wisdom implicit in the practices and beliefs derived from their forbearers—over their own intuitions and personal experiences. In many crucial situations, intuitions and personal experiences can lead one astray… (pp. 99-100)

Imitation, however, is not enough for the cultural ratcheting process to work. The other side of the coin is innovation, or the propensity to tinker with culturally evolved products. Without some level of innovation, cultural products would not change over time. And so, as Tomasello (1999) says:

The argument is that cumulative cultural evolution depends on two processes, innovation and imitation (possibly supplemented by instruction), that must take place in a dialectical process over time such that one step in the process enables the next. (p.39)

Cumulative cultural evolution requires both the conservative impulse to imitate and the progressive impulse to tinker. These two processes — imitation and innovation — make up the ratcheting effect by which complex cultural products (e.g., institutions, practices, technologies, etc.) evolve over time. Tomasello suggests that this ratcheting effect underlies most of the complex cultural products we enjoy today:

Basically none of the most complex human artifacts or social practices—including tool industries, symbolic communication, and social institutions—were invented once and for all at a single moment by any one individual or group of individuals. Rather, what happened was that some individual or group of individuals first invented a primitive version of the artifact or practice, and then some later user or users made a modification, an “improvement,” that others then adopted perhaps without change for many generations, at which point some other individual or group of individuals made another modification, which was then learned and used by others, and so on over historical time in what has sometimes been dubbed “the ratchet effect” (Tomasello, 1999 p. 5)

Nietzsche was also picking up on this dynamic. See how closely John Richardson’s description of Nietzsche’s views comes to describing the cultural ratcheting process:

[Cultural practices] are founded, on the one hand, by human’s powerful ability and will to share—to have the same values others do. But human also has the capacity, in moments of crisis especially, to remake these practices by revising the norms that guide them. So human’s remarkable development depends on a general and usual will to copy, but also on members who periodically innovate and change the content copied. (Richardson, 2020 p. 426)

According to Richardson’s interpretation of Nietzsche, our cultural norms evolve over time because of our capacity to share/copy them (i.e., imitate) and to innovate in times of crisis. This is the same process that has been outlined by modern cultural evolutionists.

Social Norms and the Herd Instinct

Understanding the cultural ratcheting process — and especially the necessity of blind imitation and copying — is necessary for understanding Nietzsche’s views about the cultural evolution of social norms. The instinct to imitate social norms is what Nietzsche refers to as the herd instinct. Although Nietzsche sometimes speaks disparagingly about this instinct, he is fully aware of how necessary it is for the human capacity for cultural evolution. As Richardson suggests:

When we see this full extent of the herd we see how thoroughly society depends on it—indeed is it. There only are societies by the power of norms, so that herding belongs to the very structure of human community. Practices can only be transmitted if there is a powerful tendency to copy: the transmission is a copying. Societies hold together and persist through generations only by the readiness of members to accept norms as their ultimate standards. Every community—every group whose members take themselves to belong to it—is a herd. (Richardson, 2020 p. 446)

Indeed, Richardson argues that Nietzsche is well aware of how totally dependent we are on this blind copying. Although Nietzsche ultimately wants us to break from the herd in order to become creative agents, it is obvious that this can only be a local break in a highly particular domain and that we must remain conformist in most aspects of our lives:

… Nietzsche can’t want or hope for anyone to give up this sharing, copying, merging tendency altogether. Although the individual is defined by his or her break from the herd, this can only ever be a “focused” or “localized” break: a refusal to copy in this and that, while continuing to accept a great background of other norms—and trying to align with groups in these. (Richardson, 2020 p. 446)

Nietzsche’s understanding of how the herd instinct originally evolved is very similar to modern cultural evolutionist’s understanding of how our innate “norm-psychology” evolved.

The Evolutionary Origins of the Herd Instinct

Maciej Chudek and Joseph Henrich, in their 2011 paper entitled “Culture–gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality” argue that humans have evolved a sophisticated norm-psychology that strongly compels us to conform to the social norms of our particular group. This drive for conformity is essentially identical to Nietzsche’s “herd instinct”. How did this norm-psychology/herd instinct evolve?

Chudek and Henrich argue that as soon as cumulative cultural evolution got off the ground sometime in the last million years or so, it would have become beneficial for groups to enforce conformity to social norms through punishment, reputation, and other social mechanisms. They cite empirical evidence that conformist tendencies arise early in childhood and persist throughout the lifespan:

Young children show motivations to conform in front of peers , spontaneously infer the existence of social rules by observing them just once, react negatively to deviations by others to a rule they learned from just one observation, spontaneously sanction norm violators and selectively learn norms (that they later enforce) from older and more reliable informants. (p. 223)

Groups with more functional social norms would have out-competed groups with less functional norms. Thus, groups had an incentive to enforce conformity to social norms within the group. As Chudek and Henrich put it:

The central theoretical insight stemming from the norm-psychology account is that once individuals can culturally learn social behavior with sufficient fidelity, self-enforcing stable states will spontaneously emerge in social groups. The self-re-enforcing nature of norms will lead to competition among groups with different norms (varying in prosociality) and to selection pressures within groups to avoid deviations. (p. 224)

This is the evolutionary origin of what Nietzsche refers to as the herd instinct. Not only do we instinctually conform to the social norms of our group, we also instinctually punish — mainly through social rejection — people who flout those norms. In this way, groups enforce conformity among their members. This is not absolute, as groups also have an interest in their members becoming individuals who are capable of transcending norms when necessary, but the necessity of individuality is always in a state of tension with the necessity of conformity.

Nietzsche, ever the observant psychologist, comments on how the herd instinct manifests in us as our fear of the disapproval of our fellow group members:

The reproach of conscience is, in even the most conscientious, weak against the feeling: “This and that is against the good custom of your society.” A cold look, a wry mouth on the part of those among whom and for whom one was raised, is still feared even by the strongest. What is really feared here? Isolation! as the argument that refutes even the best arguments for a person or cause.—So speaks the herd instinct out of us. (Nietzsche, quoted in Richardson, 2020 p. 427)

To be isolated from the group was a death sentence throughout most of human evolutionary history. Socially ostracizing a deviant group member was a relatively common punishment among pre-agricultural groups. Erik Hoel’s recent award-winning essay “The Gossip Trap” argues that “cancel culture” is the natural state of governance for human beings and that social media simply allowed it to flourish again. Our long history of this kind of punishment has instilled within us a fear of being “cancelled” by our group.

Chudek and Henrich provide an adequate explanation for the evolution of our innate “norm-psychology”, or what Nietzsche refers to as the “herd instinct”. But why do social norms differ so much among societies? And what is the process by which particular social norms proliferate over time? To answer these questions, we must refer to the concept of cultural group selection.

Cultural Group Selection and the Proliferation of Social Norms

Group selection is the idea that it is not only individuals that evolve in a Darwinian sense, but also the groups they are a part of. The idea originated with Darwin himself, who said that:

A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection. (Darwin, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex)

However, group selection as an explanation of altruism, in humans or other animals, was essentially banished from evolutionary biology in the 1960s and 70s. The 1966 monograph by biologist George Williams entitled Adaptation and Natural Selection: A Critique of Some Current Evolutionary Thought put forward a devastating critique of group selection that basically sealed the deal for most biologists. Williams convincingly argued that group selection is an implausible process and that the altruistic traits we observe in nature can be adequately explained by selection at the level of individuals.

Ever since then, the dogma in evolutionary biology has been that group selection did not play an important role in the evolution of prosociality, in humans or other species. I am in agreement with this dogma when it comes to genetic evolution. Genetic evolution is most effective at the level of the individual. Cultural evolution, however, changes the calculus in a way that invites us to re-consider the role of group selection.

As biologist Adrian Bell argued in a 2010 paper, cultural group selection is not subject to the same critiques as genetic group selection. As Bell points out, a big problem with genetic group selection is that between-group genetic differences are difficult to maintain and are easily washed out by even a small amount of migration between groups. This same problem, however, does not apply to cultural differences between groups because migrants (especially after the second generation) tend to conform to the norms and institutions of their host group. This natural conformity maintains between-group cultural differences in a way that allows for a group selection process to take place.

This process of cultural group selection does not involve genetic evolution but rather the evolution of social norms and institutions over time. W.R. Scott provides a formal definition of institutions:

Institutions are social structures that have attained a high degree of resilience. [They] are composed of cultural-cognitive, normative, and regulative elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life. (quoted in Richerson, 2016 p. 10)

Institutions like monogamous marriage, democracy, monarchy, etc., function to increase between-group differences and reduce within-group differences, thus making them a prime target for cultural group selection.

If a complex institution gives the group that adopts it an advantage in group competition, then that institution will be more likely to proliferate over time. This is how cultural group selection works. Peter Turchin, in his 2016 book Ultrasociety: How 10,000 Years of War Made Humans the Greatest Cooperator on Earth, argued that one of the major factors deciding which groups would proliferate over the last 10,000 years was simply size. All else equal, larger groups outcompeted smaller groups. This poses a problem, however, because under normal (i.e., pre-agricultural) conditions human groups fracture after they reach a certain size because of internal conflict.

Erik Hoel’s recent essay “The Gossip Trap” argues that it was this problem — the inability of groups to exceed sizes in large excess of “Dunbar’s number” (about 150 people) — that kept human beings stuck in pre-civilization for the tens of thousands of years that make up pre-history. The invention of new institutions was necessary in order for human groups to escape what Hoel calls the gossip trap:

A “gossip trap” is when your whole world doesn’t exceed Dunbar’s number and to organize your society you are forced to discuss mostly people… Being in the gossip trap means reputational management imposes such a steep slope you can’t climb out of it, and essentially prevents the development of anything interesting, like art or culture or new ideas or new developments or anything at all. Everyone just lives like crabs in a bucket, pulling each other down. All cognitive resources go to reputation management in the group, to being popular, leaving nothing left in the tank for invention or creativity or art or engineering. Again, much like high school.

And this explains why violating the Dunbar number forces you to invent civilization—at a certain size (possibly a lot larger than the actual Dunbar number) you simply can’t organize society using the non-ordinal natural social hierarchy of humans. Eventually, you need to create formal structures, which at first are seasonal and changeable and theatrical, and take all sorts of diverse forms, since the initial condition is just who’s popular. But then these formal systems slowly become real. (Erik Hoel, The Gossip Trap)

Institutions that facilitated a group’s ability to scale up in size would have been strongly selected for via cultural evolutionary processes. These institutions would have largely consisted of moral, religious, and legal structures that helped people to scale up into larger groups. For example, the anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse argues that the way human beings do religion changed dramatically after the advent of agriculture (and especially after we became literate) in such a way that religions were able to scale up to civilizations in the hundreds of thousands rather than being only applicable to a small group of familiar individuals. Any group that adopted this new form of religion (which he calls “doctrinal” as opposed to the “imagistic” religion of pre-agricultural groups) would have had a competitive advantage over other groups.

Cultural Group Selection Creates Norms and Institutions at Odds With Our Evolved Psychology

Because the proliferation of social norms and institutions due to cultural group selection occurs because of how those norms and institutions benefits the group, norms and institutions can spread over time even if they are actually bad for many of the individuals that make up the group.

For example, Peter Turchin argued in Ultrasociety that the massive increase in hierarchical organization that occurred after the advent of agriculture was basically a group-level cultural adaptation. Strict hierarchical organization was necessary at that time to scale groups up to a size that would be competitive in warfare. This hierarchical organization, however, was clearly bad for most of the people making up the society:

The first large-scale complex societies that arose after the adoption of agriculture—“archaic states”—were much, much more unequal than either the societies of hunter-gatherers, or our own. Nobles in archaic states had many more rights than commoners, while commoners were weighed down with obligations and slavery was common. At the summit of the social hierarchy, a ruler could be “deified”—treated as a living god. Finally, the ultimate form of discrimination was human sacrifice—taking away from people not only their freedom and human rights, but their very lives. (Turchin, 2016 pp. 132-133)

Hierarchical social organization proliferated because it was good for the group, not because it was good for most of the individuals making up that group. This is true of many or most culturally group selected norms and institutions, a dynamic that Nietzsche intuitively picked up on:

These valuings and rank-orders [of a morality] are always the expression of needs of a community and herd: that which benefits it first—and second and third—, that is also the highest measure for the value of all individuals. With morality, the individual is trained to be a function of the herd, and to ascribe value to itself only as function. (Nietsche, The Gay Science, 116)

A tablet of the good hangs over every people. Behold, it is the tablet of their overcomings; behold, it is the voice of their will to power. Praiseworthy is whatever seems difficult to a people; whatever seems indispensable and difficult is called good; and whatever liberates even out of the deepest need, the rarest, the most difficult—that they call holy. Whatever makes them rule and triumph and shine, to the awe and envy of their neighbors, that is to them the high, the first, the measure, the meaning of all things. (Nietzsche, Zarathustra, I. 15)

Where Do Moral Values Come From?

Now we are ready to put forward a basic idea of where our moral values come from. To put it simply, there are two sources: our genetically evolved human nature and our culturally evolved social norms and institutions. The former is the way it is because of biological selection pressures in the deep past. The latter are the way they are because of cultural selection pressures in the more recent past.

These two sources of moral values can come into conflict with each other. Sometimes social norms proliferate that conflict with our evolved nature. Both men and women, for example, have sexual instincts that evolved in the context of small-scale group life. These sexual instincts can conflict with more recent social norms around monogamy and sexual restraint. This conflict can be so pervasive that some cultures enforce strict rules that, for example, keep men and women separated most of the time or require women to dress in an extremely conservative way.

Michael Tomasello, in his 2016 book A Natural History of Morality, recognizes both of these sources of moral values. We have a natural sense of morality that largely evolved in the way that other forms of altruism evolve in nature (i.e., kin altruism, reciprocity, mutualism). On top of this, we have a uniquely human way of doing morality that involves our unique capacity to create norms and institutions.

Understanding these two sources of morality is necessary in order to understand Nietzsche’s diagnosis of modern nihilism. It was the tension created by these two (often conflicting) sources of moral values that ultimately culminated in the crisis of nihilism. Nietzsche’s argument about this, however, requires an understanding of what he meant by “master morality” and “slave morality”. The modern scientific understanding of cultural group selection can shed light on these issues.

That discussion must be reserved for the next part in this series. In part 2 I will show how Peter Turchin’s ideas about cultural group selection can explain the emergence of “master morality” in post-agricultural groups and the subsequent adoption of “slave morality” in different parts of the world during the axial age. I will argue that the dialectic between these different kinds of morality (in combination with the conflict they cause with our evolved human nature) culminated in the nihilism that characterizes the modern Western world.

Thank you for the well-written, informative, and thought-provoking post, Brett.

Great piece Brett!

I have, based on your recommendation, read John Richardson's Nietzsche's Values and I truly enjoyed it. It is pretty accessible but still enormously rich in detail, and -I agree with you- Nietzsche got a lot of things right. I was wondering whether you can recommend any other book on Nietzsche or Jung that are similar to the one I just mentioned?

Secondly, I am truly fascinated by the opponent processing that is already present in Nietzsche's thinking between, on the one hand, the agential values imposed on us by society, and -on the other- our own intrinsic values, which sometimes leads to conflicts but Nietzsche wants to align.

It reminded me of a talk that David Sloan Wilson once gave at my school here in Norway, in which he mentioned the opponent processing going on in populations of water striders. At the level of the organism, aggressive males are more successful because they get access to more mates. At the population level, however, there is selection for harmony because these groups will be more successful than others (please check the paper here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2962763/). In one of your previous posts, you mention exactly this mechanism as a driver towards more complexity. Nietzsche furthermore also holds the position that within us the drives may have conflicting goals, hence opponent processing again.