Remain faithful to the earth, my brothers, with the power of your virtue. Let your gift-giving love and your knowledge serve the meaning of the earth. Thus I beg and beseech you. Do not let them fly away from earthly things and beat with their wings against eternal walls. Alas, there has always been so much virtue that has flown away. Lead back to the earth the virtue that flew away, as I do—back to the body, back to life, that it may give the earth a meaning, a human meaning…

Let your spirit and your virtue serve the sense of the earth, my brothers; and let the value of all things be posited newly by you. For that shall you be fighters! For that shall you be creators!

Nietzsche, Zarathustra, I. 2

This will be the final essay in this series in which I set up the problem (here are links for part 1 and part 2). After this essay I will shift towards putting forward a solution to it. To recap my argument so far in this series:

Human beings have two sources of moral values: our evolved nature (studied by evolutionary psychologists) and more recently evolved cultural norms (studied by cultural evolutionists).

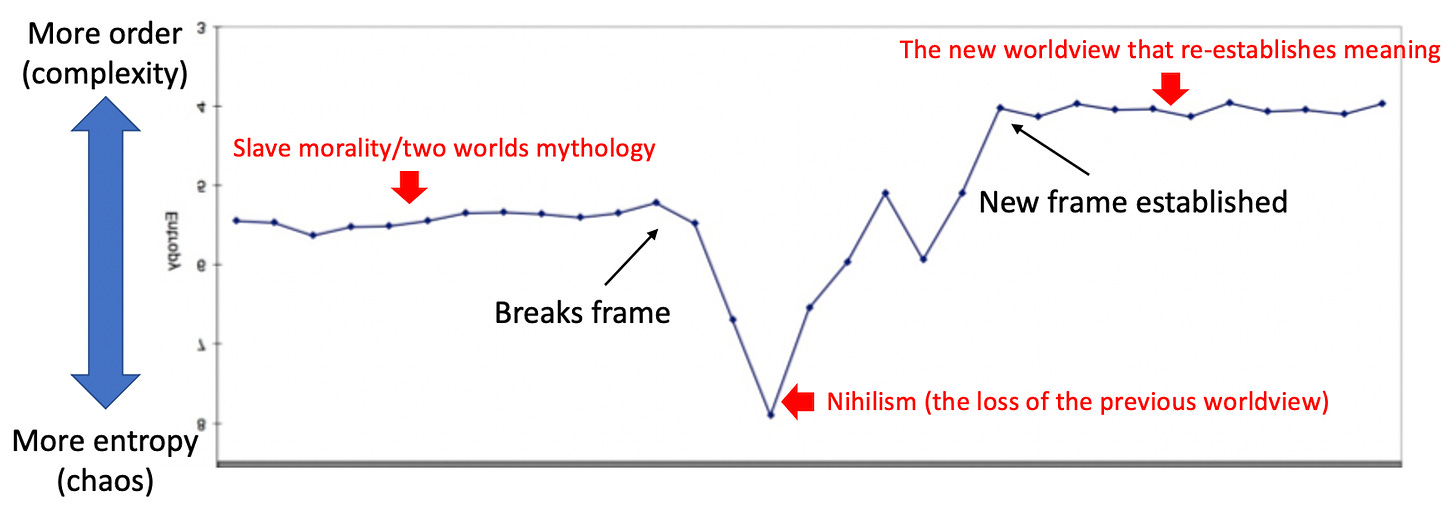

Across the ancient world, culturally evolved moral norms shifted from hierarchy-endorsing “master morality” to a more egalitarian “slave morality” during the Axial Age.

The shift to slave morality required a shift in the way one views the world at large. Unlike master morality, slave morality would require metaphysical justification for a “transcendental ethic”. Here is where we will pick up the argument.

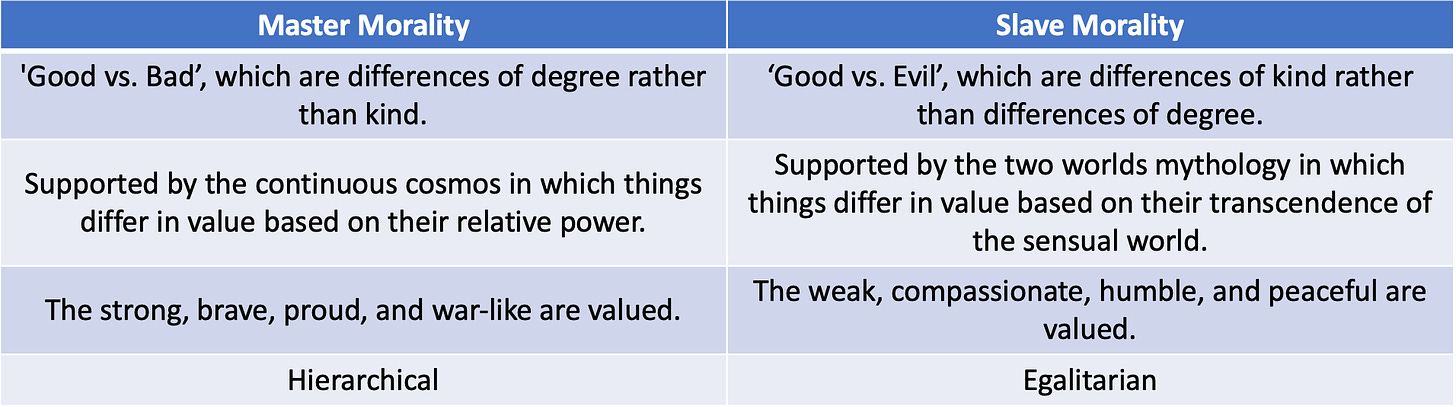

The adoption of slave morality (i.e., egalitarian, compassion-based morality) during the Axial Age radically changed the way human beings construed not only morality, but the world at large. Master morality understood the difference between the masters and the slaves as being one of ‘good vs. bad’. We (the masters) are good while they (the subjugated) are bad. Good and bad are continuous with each other. They indicate a difference of degree and not a difference of kind. The goodness of the masters was demonstrated by their power. The badness of the subjugated was demonstrated by their lack of power.

Slave morality, however, understood the difference between the oppressed and the oppressor as one of ‘good vs. evil’. Good and evil are not relative terms like good and bad. Good and evil constitute a metaphysical difference in kind rather than a difference of degree. Good and evil are also universalist, unlike good and bad. They apply equally to everyone and so must appeal to a kind of transcendental ethic (i.e., an authority that transcends the physical world). Furthermore, good and evil cannot be justified by power, since slave morality was created by the powerless and often construes the powerless as good and the powerful as evil. Good and evil must have some other kind of origin.

In order to conceptualize where good and evil come from (i.e., what their ontological basis is), one must re-conceptualize the metaphysical basis of the world at large. The re-conceptualization of the world during the Axial Age has consequences that are still relevant for us today. In this essay I will attempt to show how and why this re-conceptualization occurred during the Axial Age and what the consequences of this metaphysical turn would be for the current meaning crisis in the Western world. If you have read my previous essays on “The Illusion of Morality” (part 1 and part 2) some of this will be familiar. The story that I tell here will, by necessity, be a simplification. There is clearly more to the story than I could convey in an essay like this but I want to focus only on those aspects that are necessary to set up the problem.

I will structure the essay into three claims:

In order for morality to play its proper role, it must be construed as “objective” or as “externally imposed”. That is, it must be the kind of thing we cannot disagree about without somebody necessarily being wrong.

Master morality and slave morality had very different ways of construing themselves as objective. The objectivity of master morality was demonstrated by the power of the masters. For master morality, might made right. Because slave morality was invented by those who lacked power, it had to invent the two-worlds mythology in order to justify its objectivity.

For at least the last 2,000 years in the Western world, morality and meaning were dependent on some version of a two-worlds mythology. But now the scientific revolution has revealed the poverty of the two-worlds mythology. As such, the world seems to have lost its meaning and value for us, the inheritors of slave morality.

1. The Perceived Objectivity of Morality

What is the difference between ice cream and Nazis? That was the question asked by Kyle Stanford in his 2018 Behavioral and Brain Sciences paper entitled “The difference between ice cream and Nazis: Moral externalization and the evolution of human cooperation”. If you were to tell me that you prefer pistachio ice cream over chocolate, I would accept your opinion and move on with my life. I don’t like pistachio ice cream, but if you like it, who am I to judge? The same goes for preference in music, movies, and fashion choices. I may think you have bad taste, but I also think that we can reasonably disagree about these things without anyone necessarily being wrong. On the other hand, if you were to tell me that you would have preferred that the Nazis won WW2 over the allies, I might not be so cordial. In fact, I might act as if your preference for Nazis was objectively wrong.

The word “objective” is a slippery term. Here I am using it to refer to a statement that we cannot disagree about without somebody necessarily being wrong. The sky either is or is not lime green. If you think it’s lime green and I think it’s blue, only one of us can be correct. That means there is an objectively correct answer to the question. Similarly, the battle of Waterloo either did or did not take place. If you say it did and I say it didn’t, only one of us can be correct. Thus, “the sky is lime green” and “the battle of Waterloo took place” are objective statements. They are either right or wrong, regardless of anybody’s opinion. Whether or not chocolate is the best flavor of ice cream is not like that. Chocolate ice cream might be the best flavor for me, but pistachio might be the best flavor for you. There is no objectively best flavor of ice cream. We can disagree about it without anybody necessarily being wrong.

I am not going to attempt to answer the question of whether morality is actually objective in this essay. My answer to this question (which I will argue is actually the same as Nietzsche’s answer, properly understood) is not a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Regardless of whether morality is actually objective, however, it is clear that many people act as if morality is objective. As Stanford (2018) put it:

… we experience prototypical moral norms, demands, and obligations as imposed unconditionally, irrespective of not only our own preferences and desires, but also those of any and all agents whatsoever, including those of any social group or arrangement to which we belong: We apply them not only to ourselves and our fellow community members, but also to absolutely any candidate social partner with whom we might interact, no authority is capable of suspending the demands they impose, and we regard violations of them as more serious and more deserving of punishment than violations of the merely conventional rules that we collectively self-impose. There is correspondingly less room for intersubjective disagreement without error concerning them, indeed nearly as little as in the case of empirical or scientific fact. (p. 9)

In other words, people often treat moral preferences as if they are the kind of thing that one can be objectively wrong about. If you say that Hitler was a good guy, most people will act as if you have said that the sky is lime green. Psychologists Geoffrey Goodwin and John Darley carried out three experiments to determine when and why people treat moral norms as objective. They use the same definition of objectivity as I do here (i.e., whether or not it is possible to disagree without anybody being wrong). Some key findings from their studies are that:

Ethical statements (e.g., about the morality of committing murder or robbing a bank) were rated almost as objective as factual statements (e.g., about geography) and much more objective than statements about taste or preference (e.g., music preferences).

The degree to which somebody finds an ethical claim to be objective is predicted by how strongly they hold that ethical belief.

The most consistent predictor of whether people generally hold ethical beliefs to be objective was whether or not they grounded these beliefs in the existence of God.

In his 2018 paper, Kyle Stanford puts forward an explanation of this phenomenon. Why do people so often treat moral statements as objective? In short, it’s because morality only works when nearly everyone in a group agrees about it. As Jonathan Haidt has argued, one of the functions of morality is to bind groups of people together. This binding function doesn’t work if half of the group disagrees with the other half about some important moral norm. Construing morality as being externally imposed or as being objective makes disagreement much more difficult. The person who would disagree about the sky being blue is a madman. And this is not far off from how we treat those who disagree with us about morality. To disagree with a well-established moral norm, one must be either evil, stupid, or insane. Is this not how we would treat someone who said that Hitler was on the right side of history? And does this not make it easier to ostracize that person? Thus, construing morality as objective makes it easier to enforce moral norms.

This does not mean that morality is actually objective. It just means that treating it as such is a useful strategy for enforcing the moral norms that bind groups of people together.

From Continuous Master Morality to Disembedded Slave Morality

In the third video of John Vervaeke’s Awakening From the Meaning Crisis YouTube series, he discusses an important shift in worldview that occurred during the Axial Age. Vervaeke suggests that there was a “great disembedding” where we moved from a “continuous cosmos” to a “two-worlds mythology”.

In pre-Axial societies like ancient Greece, human beings thought of themselves as being continuous with both the rest of nature and with divinity. Differences between things were differences of degree rather than of kind. The most important difference between entities was the amount of power they had. The difference between human beings and gods was not a moral or metaphysical difference, but rather consisted of the fact that the gods were more powerful than regular people. The gods of the ancient Greeks might be morally flawed from our perspective, but they are still considered gods because of their great power.

The Axial Age, as it manifested in both Greece and Israel (to be focused on because these are the two main influences on Western civilization), disrupted this worldview. Vervaeke refers to this disruption as the great disembedding. We went from a continuous cosmos to one in which there are two worlds: the everyday world of sensory experience and the transcendent world of divinity. This happened in both Greece (largely via Plato) and Israel, with these strands later being synthesized through Plato’s influence on Christianity. At the same time, we transitioned from a morality in which continuous ‘good vs. bad’ became dichotomous ‘good vs. evil’.

Nietzsche believed that (especially in Israel) the shift from a continuous cosmos to the two worlds mythology was driven by the change in morality that was occurring at the same time. This argument can be summarized as such:

The objectivity of master morality was grounded in power differentials. The masters were more powerful than the subjugated and therefore their preferences were right and good. The power of the masters was self-evident justification for the rightness of their moral preferences.

Because slave morality was created by people who lacked power, the objectivity of slave morality would need a different kind of justification. An unobservable transcendent world from which moral norms emanated would serve to justify the objectivity of slave morality.

This is a simplified story, of course, and there are differences in how this occurred in Greece and Israel, but it serves to make my point: the continuous cosmos was compatible with master morality but was incompatible with slave morality. As such, the “great disembedding” was a necessary consequence of the shift from a morality based on ‘good vs. bad’ to one based on ‘good vs. evil’. I reviewed the origins of this shift in the previous essay in this series.

What does good mean in slave morality? In a nutshell, the ‘good’ of slave morality is everything that benefits others at the expense of yourself. You should be humble, charitable, and compassionate. To be prideful, greedy, or cruel is to be evil. The dichotomy here is between the “egoistic” and the “unegoistic”, as Nietzsche put it. That which stems from egoistic concern is evil, while that which stems from pure concern for others is good. The objectivity of this morality was backed up in a variety of ways, but in Christianity it was basically because God wanted you to act that way. As such, the fact that people who believe in God are more likely to construe their moral values as objective (as was found by Goodwin & Darley) is unsurprising.

The table below reviews the relevant differences between master and slave morality.

The Meaning Crisis

Slave morality and the two worlds mythology are intimately connected. The two worlds mythology provides the metaphysical foundation for slave morality to make claims about the nature of good and evil. In the last 400 years or so, this connection has been disrupted in a variety of ways. Scientific findings have disrupted the foundations of the two worlds mythology, including the discovery that the earth is not at the center of the cosmos, the discovery of gravity (which made the forces acting in the heavens continuous with those on earth), and perhaps most importantly the discovery of the process of Darwinian evolution.

Darwinian evolution disrupted the two worlds mythology in two major ways: in the first place, it made it harder to believe in some kind of transcendent creator God, since the forms of organisms could now be explained via their history of selection. In the second place, it made human beings continuous with the rest of nature. There is no metaphysical difference between human beings and other animals. In a variety of ways, the scientific worldview is returning us to the continuous cosmos.

Darwinian evolution also disrupted one of the precepts of slave morality by making it more difficult to believe in the possibility of unegoistic actions. Even though cooperation and some kinds of altruism are common in nature, they can all be explained through the benefits they provide for the “selfish genes” of the organisms that display them. In a 2001 book chapter on mutualistic hunting, Michael Alvard said that:

Altruism has proven to be an essential concept within the evolutionary study of social behavior, but in many ways it has been a strawman. Altruism is a behavior that increases the fitness of others and decreases the fitness of the actor—and by definition will be selected out of a population… In fact, none of the hypotheses current in the literature evoke genuine altruism to explain cooperative behavior… Altruism is a behavior that favors others over self and, as a result, will not evolve. (p. 263)

The Darwinian view of life suggests that apparently altruistic acts are ultimately motivated by “selfish” motivations, i.e., the organism’s inclusive fitness interests (I discussed inclusive fitness in more detail in the first essay in this series). Since slave morality has been predicated on the possibility of unegoistic motivations, this constitutes a blow to a major precept of slave morality.

Another blow to slave morality was that the new scientific conceptions of the world made it harder to believe in free will. Slave morality held people responsible for their “evil” acts because it construed those acts as being produced by somebody who could have chosen otherwise. In other words, moral responsibility depended on some kind of free will. But the Darwinian revolution, in addition to the Newtonian revolution in physics, both painted a picture of a deterministic, causally closed world in which unconstrained free will had no role to play.

It was these two realizations: the realization of the impossibility of pure altruism and the realization of the impossibility of unconstrained free will, that were among the most important precursors of modern nihilism. As Nietzsche put it:

The nihilistic consequence (the belief in valuelessness) as a consequence of moral valuation: everything egoistic has come to disgust us (even though we realize the impossibility of the un-egoistic); what is necessary has come to disgust us (even though we realize the impossibility of any liberum arbitrium or “intelligible freedom”). We see that we cannot reach the sphere in which we have placed our values; but this does not by any means confer any value on that other sphere in which we live… (Will to Power 8)

Nietzsche also recognized the advent of modern nihilism as being a result of the loss of the two worlds mythology. As he put it:

The supreme values in whose service man should live, especially when they were very hard on him and exacted a high price—these social values were erected over man to strengthen their voice, as if they were commands of God, as “reality,” as the “true” world, as a hope and future world. Now that the shabby origin of these values is becoming clear, the universe seems to have lost value, seems “meaningless”—but that is only a transitional stage. (Will to Power 7)

So we can summarize the advent of modern nihilism as such:

We grounded our values in a two worlds mythology, in the possibility of unegoistic actions, and in an unconstrained free will.

The scientific revolution has made it difficult or impossible for us to believe (at least in the same way that we once did) in the two worlds mythology, in the possibility of unegoistic actions, or in an unconstrained free will.

As such, our moral values, from which we derived great meaning in life, are found to be groundless. Consequently, the world appears to have been drained of meaning and value.

If we ground our values in premises that we no longer believe in, this can only lead to one of two possible results, which have been called passive nihilism and radical nihilism. We can either stop valuing what we valued before (even though we have nothing to replace it with; i.e., passive nihilism) or we can accept that our highest values are unrealizable in the world as it actually exists, and therefore cast moral judgement upon the world (i.e., radical nihilism). Passive nihilism corresponds to a lack of values. Radical nihilism corresponds to the idea that the world is inherently evil.

Passive nihilism: The belief that nothing is of value. In action, this tends to manifest as the pursuit of values that are vulgar, low, or common, since nobody can actually live (or act) without implicit or explicit values. Passive nihilism is therefore the devaluation of the highest values.

Radical nihilism: The feeling that one’s highest values are unrealizable in the world, such that the world is inherently evil or unfair. In the extreme, this can result in a desire to destroy the world (or society).

The refrain of passive nihilism is something like: “Nothing matters, so why bother doing anything?”. The refrain of radical nihilism is something like: “The world is inherently evil, so it shouldn’t even exist”. Both passive and radical nihilism result from the fact that our values were grounded in presuppositions about the world that we can no longer believe in. Nietzsche, despite being often labelled as a nihilist, believed that nihilism was a pathology to be overcome. Nihilism is a pathology that results from a false generalization:

Nihilism represents a pathological transitional stage (what is pathological is the tremendous generalization, the inference that there is no meaning at all)… (Will to Power 13)

One meaning (grounded in slave morality and its presuppositions) has been falsified, but does that mean that there is no meaning at all? This is a false generalization. Past peoples have grounded their values and their meaning in different presuppositions. There is no reason to think that the meaning which was lost is the only possible meaning that we can aspire to.

Science and the Continuous Cosmos

The scientific revolution has disrupted the worldview in which our meaning and values were previously grounded. As John Vervaeke pointed out, the scientific worldview, perhaps especially Darwinian evolution, is returning us back to the continuous cosmos. Nietzsche’s recognition of this disruption motivated him to put forward a new understanding of the world. In his 1950 book on Nietzsche’s philosophy, Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche’s greatest translator, said that:

Nietzsche was aroused from his dogmatic slumber by Darwin… [Darwin’s theory indicated that] The ancient theological picture of man is gone… The problem is whether it is possible to give man a new image of himself without introducing supernatural assumptions that experience does not warrant and that we cannot, with integrity, fail to question. (p. 167)

As John Vervaeke has put it, the task here is to find the sacred (i.e., that which is objectively valuable) outside of the supernatural. Science disrupted the coherency of the worldview of Western people and therefore disrupted our grounding of values and our sense of meaning. Could it be that science can also help us to put the world back together? Nietzsche believed that it could:

All the sciences have now to pave the way for the future task of the philosopher; this task being understood to mean that he must solve the problem of value, that he must fix the hierarchy of values. (Genealogy of Morals, I. 17)

That is the task that I will be addressing for the rest of this series. Whereas for the last 2,000 years or more, the objectivity of value judgements was grounded in the two worlds mythology, we must now find a way to ground value judgements in the continuous cosmos revealed to us by the scientific enterprise. This is what Nietzsche means when he enjoins us to be “faithful to the earth” in the opening quotation. For too long have we believed that the true value of things is to be found in an other-worldly realm, a “true” world, a heaven, or whatever it may be. To argue that true value can only be obtained by positing a transcendent world is to commit slander against the only world that actually exists. Value is to be found in the world, or nowhere.

The trick here is to avoid two different kinds of mistakes: We can avoid nihilism by pretending that the old ways of thinking are still viable. This is what the religious fundamentalists of all stripes do. They have not incorporated the Darwinian revolution (and other scientific disruptions to their worldview) because they know what it will do to their cherished beliefs and values. But stasis is death. The world has changed and our conceptions of it must either change too or be rendered obsolete.

The other mistake is to wallow in, or even celebrate, nihilism — to accept it as an end state and as the necessary consequence of the scientific revolution. Nietzsche believed that the correct path was not to avoid nihilism or to accept it as an end state, but rather to pass through nihilism as a necessary stepping stone on the way to something better. Nietzsche believed that we must allow our previous conception of the world to die off, but we should not wallow in or celebrate this death as an end point. Rather, we must find a new conception of the world that once again re-establishes meaning. I will quote Nietzsche at length on this point:

He that speaks here… has found his advantage in standing aside and outside, in patience, in procrastination, in staying behind; as a spirit of daring and experiment that has already lost its way once in every labyrinth of the future; as a soothsayer-bird spirit who looks back when relating what will come; as the first perfect nihilist of Europe who, however, has even now lived through the whole of nihilism, to the end, leaving it behind, outside himself.

For one should make no mistake about the meaning of the title that this gospel of the future wants to bear. “The Will to Power: Attempt at a Revaluation of All Values”—in this formulation a countermovement finds expression, regarding both principle and task; a movement that in some future will take the place of this perfect nihilism—but presupposes it, logically and psychologically, and certainly can come only after and out of it. For why has the advent of nihilism become necessary? Because the values we have had hitherto thus draw their final consequence; because nihilism represents the ultimate logical conclusion of our great values and ideals—because we must experience nihilism before we can find out what value these “values” really had.— We require, sometime, new values. (Will to Power 3-4)

Any attempt at a revaluation of values presupposes nihilism and can only grow out of it. This is because nihilism represents the loss of the previous structure of meaning. Only when we have emptied the cup can we fill it with a new drink. This is the same process as that which underlies an insight that I have described in previous essays (e.g., here). Nihilism represents the “descent into chaos” or the increase in entropy that precedes the insight, i.e., the adoption of a new frame. As such, nihilism is a necessary step in the process. The figure below is meant to show the overlap between this process and the structure of an insight, which is the same as the structure of any phase change in a complex system.

In the following essays, we will see how scientific advancements in complexity science, cognitive science, evolutionary psychology, the scientific study of consciousness, and more can help us to solve the problem of value described by Nietzsche above. I will also show how Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ thesis foreshadowed all of this.

Knowing this is somewhat tangential to the point you were making regarding determinism and enlightenment physics; later advances in math and physics may not have overturned determinism but did essentially make deterministic understanding of the universe impossible. Godel’s incompleteness theorem, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, quantum physics in general. Some do take uncertainty as fundamental rather than a lack of knowledge, but that weakens the determinism aspect as breaking down the old world view. Plenty of ‘room for god’ when there are boundaries to knowability.

I think attention is the key to unlocking new values. In addition to inheriting two-worlds mythology, the arena of information (and especially visual information) has outpaced and overwhelmed agents of biological evolution. To keep up, we break everything down into atomized bits. To glue the continuum back together we need to balance the sensorium again, and attention is the finger on the scale. We have to unupholster objects with a piercing inner gaze, to get at empty fruit inside that nourishes.

But maybe this is one of the "mistakes" you laid out, as seems to hearken to a tribal everything-all-at-once consciousness. Or perhaps a mix of tribal sensory equanimity with modern meta awareness of big history to instill a base of gratitude.

Looking forward to next installments!