The Revaluation of All Values, Part 2

Master morality and slave morality in light of cultural group selection

*Note: See here for part 1

“War is father of all, and king of all. He renders some gods, others men; he makes some slaves, others free.”― Heraclitus

In the previous essay in this series I discussed Nietzsche’s account of the origin of moral values in light of the modern sciences of evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution. In this essay I will describe Nietzsche’s account of “master morality” and “slave morality” in light of cultural group selection (I described cultural group selection in more detail in the previous essay).

For the purposes of these essays, I hope that we can put aside our own moral prejudices and refrain from seeing either master or slave morality as being better or worse than the other. At least for the time being, it would be better to approach these issues with the attitude of a detached anthropologist. Value judgements will come later.

Contrary to popular belief, it was not Nietzsche’s intention to take the side of “master morality” over “slave morality”. Although it may seem as if Nietzsche is firmly on the side of master morality, this is largely because he thinks slave morality has so thoroughly dominated Western culture. The subtitle of his book The Genealogy of Morals: A Polemic indicates his purpose. He is engaging in an explicitly polemical exercise in order to undermine our own moral prejudices, which (as good Western people) inevitably lead us to side with slave morality. In reality, Nietzsche’s ideal was a synthesis of master and slave, what he once referred to as “The Roman Ceasar with Christ’s soul.” (Will to Power 983)

The Roman Ceasar with Christ’s soul represents, in Karl Jasper’s words, one of “the most amazing attempts to bring together again into a higher unity what [Nietzsche] has first separated and opposed to each other … Nietzsche imagines… the synthesis of the ultimate opposition.”

Nietzsche’s ideal — the synthesis of master and slave — is somebody who is capable of both sympathy and hardness, who has claws (i.e., the capacity for cruelty and aggression) but can choose not to use them.

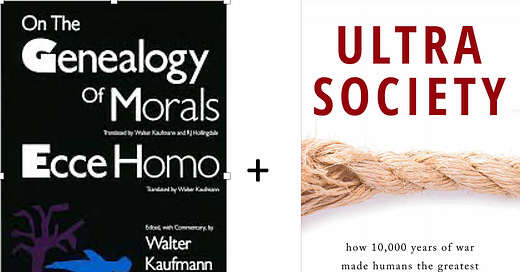

Peter Turchin’s 2016 book Ultrasociety: How 10,000 Years of Warfare Made Humans the Greatest Cooperators on Earth provides a framework that can explain why master morality was widely adopted after the advent of agriculture and why slave morality eventually replaced it across the ancient world during the Axial Age.

What is Master Morality?

Nietzsche has a rich description of the psychological underpinnings of both master and slave morality that I will explore in a future essay. In this essay I am mainly concerned with how these moralities manifest at the group level. In his 1996 book Nietzsche’s System, John Richardson summarizes Nietzsche’s conception of master morality, which is:

… when a warlike people or tribe subjugates a weaker one and forces it into a hierarchic or aristocratic society, sharply divided between the ruling and ruled castes. The achievements and situation of the ruling group encourage its members to value in a certain way: in their happiness and confidence in themselves and their success, the masters count themselves 'good', while with mild contempt they look down on the others as 'bad'. This way that they rank persons or lives is of course their 'master morality' (Nietzsche’s System 1.5.1)

Compare Richardson’s description of master morality with Peter Turchin’s description of the first complex societies to rise in the wake of the advent of agriculture:

The first large-scale complex societies that arose after the adoption of agriculture—“archaic states”—were much, much more unequal than either the societies of hunter-gatherers, or our own. Nobles in archaic states had many more rights than commoners, while commoners were weighed down with obligations and slavery was common. At the summit of the social hierarchy, a ruler could be “deified”—treated as a living god. Finally, the ultimate form of discrimination was human sacrifice—taking away from people not only their freedom and human rights, but their very lives. (Turchin, 2016 pp. 132-133)

Human beings lived for hundreds of thousands of years mainly in relatively egalitarian tribes of nomadic hunter-gatherers. What was it about the advent of agriculture that caused human groups to put aside the often-times fierce egalitarian ethos that characterizes pre-agricultural groups and adopt extremely hierarchical and even despotic forms of social organization? Turchin argues that the rise of hierarchical societies occurred mainly due to their advantage in warfare:

…the first leap in social complexity, from nonhierarchical, independent communities to centralized complex chiefdoms and the first states, was invariably associated with a dramatic increase in inequality. The question is, what was the specific evolutionary mechanism that allowed larger societies to outcompete smaller ones, despite the downside of despotism? And the most obvious candidate, it seems to me, is war. War is the reason why big states emerged. No other explanation really makes sense[…] we have seen that war was the chief preoccupation, to the point of tedium, of archaic kings like Tiglath Pileser. We don’t find boastful inscriptions from Ashurnasirpal about trading networks or well-maintained irrigation systems. In their own official statements, the first kings were all about war. Shouldn’t we pay attention to what they tell us? (p. 156)

Hierarchically organized societies were capable of scaling up in a way that more egalitarian ones were not. This allowed them to put more soldiers on a battlefield, which was a huge advantage in plains warfare involving mostly foot soldiers. Furthermore, hierarchical organization provided a clear chain of command that made military coordination more efficient and effective. There’s a reason that all militaries today still maintain a strict hierarchy of command. It’s because all of the militaries that aren’t organized that way lose. Although his explanation is slightly different from Turchin’s, Nietzsche also recognizes that war played a pivotal role in the formation of early states:

I employed the word “state”: it is obvious what is meant—some pack of blond beasts of prey, a conqueror and master race which, organized for war and with the ability to organize, unhesitatingly lays its terrible claws upon a populace perhaps tremendously superior in numbers but still formless and nomad. That is after all how the “state” began on earth… (Genealogy of Morals, II. 17)

It is clear that many archaic states did begin with a conquest like the one described above by Nietzsche. Many, however, did not. For example, Turchin argues that Egypt began with a drive for unification that came from within Egypt rather than being imposed upon it by an outside force. Either way, both Nietzsche and Turchin recognize the importance of warfare in the early formation of hierarchically organized despotic states. The “master morality” of those at the top of these societies served to justify their position and considered everyone at the bottom ‘bad’ or ‘low’ or ‘ignoble’, etc.

We now have compelling genetic evidence for despotism in early agricultural societies. About 10,000 years ago, right as agriculture was beginning to spread, there was a massive change in the operational sex ratio for many human groups (i.e., the number of reproducing women for every man). Under normal circumstances there have been about 2-3 reproducing women for every reproducing man. This reflects the facts that a) most women have some children, b) some men have a lot of children, and c) many men have no children. Genetic evidence suggests that during the early stages of the agricultural revolution, this ratio shot up to 17:1 (see here and here for the evidence). This means that during this time period there were 17 reproducing women for every reproducing man. If this evidence is reliable, that is an astonishing number. Most likely it means that either a) most men died very young, before they could have children, b) a small number of men amassed massive harems of women and excluded all the other men from reproducing, or c) some combination of the above.

Whatever was going on in these societies, it’s clear that some of the men became extremely powerful and successful while most men died before ever having children. Presumably this is related to the extreme shift towards hierarchical organization and inequality that happened around this time.

The men at the top of these societies justified their power with reference to religious and ideological claims that construed themselves as ‘good’ (noble, righteous, chosen by the gods, etc.) and everyone beneath them as ‘bad’ (ignoble, common, slavish, etc.). This is their “master morality”.

Those at the bottom of these societies, those subjugated by the “masters”, did not passively accept their subjugation. Their hatred for and resentment of the masters would eventually become creative and spawn a new kind of morality — one which would seek to temper the masters’ claims of superiority. This is the origin of “slave morality”.

What is Slave Morality?

During the time period known as the “Axial Age” (about 900-300 BC), there was a series of religious and philosophical revolutions across the ancient world. In Greece, this coincides with the time of Plato and Socrates. In Israel, this was the time of the Old Testament prophets. In India, Jainism and Buddhism. In China, Confucianism and Taoism.

Many of these religious revolutions represented a turn towards a more peaceful, compassionate, egalitarian form of morality:

The most remarkable feature of all the Axial religions is the sudden appearance of a universal egalitarian ethic, credited by Bellah to “prophet-like figures who, at great peril to themselves, held the existing power structures to a moral standard that they clearly did not meet.” Bellah calls these figures, who scorned riches and passed harsh judgment on existing social conditions, “renouncers” (and, in their fiercer strain, “denouncers”). Renouncers abandoned their worldly status as husbands and workers for a life of asceticism and travel. (Turchin, 2016 p. 191)

Across the world during the Axial Age, renouncers and denouncers spoke out against the despotic nature of the current rulers in their societies (the “masters”, as Nietzsche might call them). Turchin points out that this new morality was eventually adopted by the rulers in these societies. Across the ancient world, rulers began relating to their people in a new way. At least on the surface, they began to rule according to compassion and a sense of duty rather than the entitlement that characterized the “God-kings” of more archaic societies:

This is not to deny that there have been plenty of wicked kings in the past 2,500 years. Most likely they were in the majority. Nevertheless, the new trend was that rulers were at least supposed to be good. And many did try to govern in ways that benefited the common people, not just the ruling class. This remarkable turnaround happened virtually simultaneously in the Mediterranean, the Near East, India, and China. (Turchin, 2016 p. 187)

As Nietzsche pointed out, these new moralities represented an almost complete inversion of the morality of conquest and domination that preceded them. Although Christianity is not technically an Axial Age religion since it appeared about 300-400 years after the Axial Age, it is undoubtedly in the spirit of the other Axial Age religions with its focus on moral equality and neighborly love. In his 2014 book Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Individualism, Larry Siedentop argues that Christianity represented an inversion of the more hierarchical Greek and Roman view of the world:

At the core of ancient thinking we have found the assumption of natural inequality. Whether in the domestic sphere, in public life or when contemplating the cosmos, Greeks and Romans did not see anything like a level playing field. Rather, they instinctively saw a hierarchy or pyramid. Different levels of social status reflected inherent differences of being[…] so entrenched was this vision of hierarchy that the processes of the physical world were also understood in terms of graduated essences and purposes – ‘the music of the spheres’. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 51)

This hierarchical view of things is of course the “master morality” characterized by Nietzsche. These Greeks and Romans did not believe in moral equality. They saw a hierarchy of beings with themselves at the top. Christianity represents a radical inversion of this idea.

Paul’s conception of the Christ overturns the assumption on which ancient thinking had hitherto rested, the assumption of natural inequality. Instead, Paul wagers on human equality. It is a wager that turns on transparency, that we can and should see ourselves in others, and others in ourselves. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 60)

In reality, however, Paul’s conception isn’t really about equality. In fact, Paul is clear that the low, weak, and humble are better in the eyes of God than the powerful and prideful. This represents a complete reversal of the previous hierarchy of value judgements.

In a 2022 paper entitled “Nietzsche: Three Genealogies of Christianity”, Michael Forster points out the many ways in which Christianity represents a nearly exact inversion of the Homeric “master” morality of the ancient Greeks and Romans. It is worth laboring on this point because it tells us something about what slave morality actually is. Slave morality is a spiritual and moral rebellion against the masters. Nietzsche argued that slave morality does not really create new values (although it may be creative in other ways). Rather, it inverts the values of the masters. Slave morality is therefore always reactive:

While every noble morality develops from a triumphant affirmation of itself, slave morality from the outset says No to what is “outside,” what is “different,” what is “not itself”; and this No is its creative deed[…] in order to exist, slave morality always first needs a hostile external world; it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all—its action is fundamentally reaction. (Genealogy of Morals, I. 10)

The oppressed look to their oppressors and determine what they value. The masters value honor and glory? Then it is the honorless who will be exalted. The masters value power? Then it is the powerless who are good. The masters are warlike and brave? Then the weak and meek shall be praised. In this way, slave morality is an inversion of master morality. Michael Forster points out seven ways in which Christianity represents an inversion of Homeric Greek and Roman morality:

Homeric morality greatly values honor and renown. The New Testament inverts this valuation: “Blessed are ye when men shall hate you, and when they shall separate you from their company, and shall reproach you, and cast out your name as evil,” but “Woe unto you, when men shall speak well of you” (Luke, 6:22, 26).

Homeric morality admires the warlike and brave. The New Testament inverts this valuation: “Blessed are the peacemakers”; “Blessed are the poor in spirit ... Blessed are the meek” (Matthew, 5:9, 3–5).

Homeric morality admired the politically powerful and despised the politically powerless. The New Testament inverts this valuation: “Whosoever exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted”; “The kings of the gentiles exercise lordship over them; and they that exercise authority upon them are called doers of good. But ye shall not be so: but he that is greatest among you, let him be as the younger; and he that is chief, as he that does serve” (Luke, 14:11, 22:25–26).

Homeric morality admired the rich and despised the poor. The New Testament inverts this valuation: “Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal: But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven”; “Blessed be ye poor ... Blessed are ye that hunger,” but “Woe unto you that are rich! ... Woe unto you that are full!”; “It is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” (Matthew, 6:19–20; Luke, 6:20–25, 18:25)

Homeric morality admired the man who took revenge on those who transgressed against him but despised the man who failed to do so (e.g., the central plots of the Iliad and the Odyssey). The New Testament inverts this valuation: “Love your enemies, do good to them which hate you. Bless them that curse you, and pray for them which despitefully use you. And unto him that smiteth thee on the one cheek offer also the other” (Luke, 6:27–29)

Homeric morality admired having skill at deception and lying (e.g., Odysseus) but tended to despise those who lack this skill. The New Testament inverts this valuation, stating that we “have renounced the hidden things of dishonesty, not walking in craftiness, nor handling the word of God deceitfully; but by manifestation of the truth, commending ourselves to every man’s conscience in the sight of God” (2 Corinthians, 4:2).

Homeric morality admired the enjoyment of bodily pleasure, especially sexual pleasure, and despised the failure to achieve it. The New Testament inverts this valuation: “To be carnally minded is death; ... the carnal mind is enmity against God ...; they that are in the flesh cannot please God” (Romans, 8:6–8). (Forster, 2022)

This total inversion of Homeric master morality is largely why Nietzsche regarded Christianity as slave morality par excellence. He did not attribute this inversion to Jesus Christ (who he believed had been misunderstood by mainstream Christians), but rather to Paul. For Nietzsche, there is perhaps no better exemplar of slave morality than the famous words of Paul in Corinthians:

… God has chosen the foolish things of the world to shame the wise, and God has chosen the weak things of the world to shame the things which are strong, and the insignificant things of the world and the despised God has chosen, the things that are not, so that He may nullify the things that are, so that no human may boast before God. (Corinthians 1:27-29)

Paul, in other words, says that the losers are actually the winners, at least in God’s eyes. For Nietzsche, this is what slave morality represents. It is the morality of the losers, taking their imaginary revenge against the winners.

The Axial Age moralities of egalitarianism, compassion, and restraint of power were massively successful in the ancient world. Christianity eventually became the official religion of the Roman empire and went on to become the most popular religion in the world. As with the rise of master morality, we can also understand its usurpation by slave morality using the framework of cultural group selection.

The seeds of slave morality had been there ever since hierarchical social structures had arisen thousands of years before the Axial Age. Presumably, oppressed people had always been resentful about being oppressed. It was only, however, when the message “fell on good soil” during the Axial Age — when military conditions made it necessary for civilizations to scale up in size — that slave morality actually took hold and began to proliferate.

…the pattern of a universal empire administered in the name of a universal religion first emerged during the Axial Age. Achaemenid Persia promoted Zoroastrianism. Ashoka Maurya converted to Buddhism. Han China had Confucianism. The Roman Empire converted to Christianity. The rise of such religions was momentous enough. Even more crucial was the appearance of the egalitarian ethic associated with them. (Turchin, 2016 p. 203)

One of the best predictors of who would win in ancient warfare was simply the number of men one could put on a battlefield. Warfare was largely a numbers game. As it turns out, people don’t like to risk their lives for leaders who oppress them — oppressed peoples don’t flock to the battlefield to fight for their oppressors. It also turns out that voluntary soldiers make for much better warriors than conscripted slaves. Besides that, it’s generally a bad idea for a despotic emperor to give a bunch of weapons to the people he is oppressing. All of this meant that leaders who adopted a more egalitarian, compassionate ethic were better able to persuade their people to fight for them.

As the need for greater size became more pressing, the old style of leadership, in which God-kings ruled their people without compassion or any sense of duty, became less and less viable:

In short, the despotic states couldn’t survive in the new military environment. Many were simply wiped off the map. In others, there must have been unease among the elites that made them more receptive to the message preached by the denouncers. In such states, the new egalitarian message fell (as one of the later denouncers might have put it) on good soil. (Turchin, 2016 p. 204)

And so we see, as Peter Turchin has pointed out, a zig-zag pattern in levels of inequality throughout human history. We started off as relatively egalitarian nomads. We then transitioned to the massive hierarchy and inequality of early agricultural states. We then experienced the more egalitarian Axial Age revolutions which tempered the power of despotic rulers. In each case, the transition was driven by the need to scale up in size in order to compete with neighboring groups. Turchin refers to this as a process of “destructive creation”, which is quite interesting given that the idea of destructive creation was introduced to the social sciences via the writings of Nietzsche (see here for a detailed account of this idea).

Thus, although different in detail, Turchin’s ideas about destructive creation are quite Nietzschean in spirit.

The Metaphysics of Slave Morality

Historical sociologist Garry Runciman (in his chapter entitled “Righteous Rebels” in this 2012 book) suggests that ancient Greek and Roman morality (which correspond to Nietzsche’s “master morality”) were similar in that they both centered on respecting tradition and maintaining the integrity of the state. He suggests that these moralities did not appeal to a “transcendental ethic” but rather to the authority of tradition, conformity, and the maintenance of order. Axial Age “slave” moralities were rather different from this:

Whatever disagreements there may be among historians about the provenance, nature, and scope of the intellectual innovations originating in Israel, Greece, Iran, China, and India during Karl Jaspers’ “Axial Age,” the emergence of critical reflection on the source and use of political power by reference to some transcendental ethical standard marks a major transition in human cultural evolution. (Runciman, 2012 p. 317)

As Runciman points out, there are a variety of ways in which Axial Age religions can appeal to a transcendental ethic:

The appeal to a transcendental ethic may be bound up with a variety of answers to the question of the origin of evil as such: the Zoroastrian conception of Ahura Mazda as the beneficent creator confronted by Angra Mainyu as the personification of evil is only one among others. But once rulers are seen not merely as impious, or untrustworthy, or alien, but as allies or servants of evil against good, then whatever the explanation given of the existence of evil in the world, the allies or servants of the good are morally in the right if they rise up against them. (ibid., p. 323)

The appeal to a transcendental ethic took on particular forms in Greece and Israel (largely via Plato and the Old Testament prophets). Christianity eventually synthesized these two traditions. In a future essay I will look at the strategies used during the Axial Age that allowed reformers to appeal to a transcendental ethic. We will see how these strategies worked at the time, and were perhaps highly functional and necessary, but eventually culminated in what Nietzsche called the “death of God” and the advent of the meaning crisis in the Western world.

In anthropology, there is an interesting literature on some necessary conditions for the emergence of hierarchical societies (as opposed to egalitarian societies). From what I've understood so far, it seems that one of the major determinants of dominance hierarchy (not prestige, but hierarchical and extractive relationships, and, to be efficient, rationalized / legitimides) is whether resources are monopolizable, which in turn depends on the predictability, density and defensibility of resources - which is why societies with delaued economies such as agriculture tend to be more hierarchical than societies with immediate economies such as hunter-gatherers. When resources are monopolisable, the necessary conditions for social domination are present:

1) Group A / dominus has no other source of resources better than the submission, obedience, or "forced cooperation" of group B / servus (when group A has better sources of resources than group B's extraction, group B is ignored, is a competitor for the same resources, or is eliminated/exterminated by group A);

2) Group A controls the resources that group B needs (and here comes the question of the monopoly of resources exercised by group A);

3) Group B has no other source of resources better than submitting to the hierarchy (cooperate, obey) imposed by group A (if group B has better sources of resources, such as simply leaving where group A is, it does not exist reason for group B to benefit group A through its own losses).

There is social dominance in both nomadic hunter-gatherer societies and agricultural societies, but about 10,000 years ago (domestication of plants and animals), we started to see a predominance of hierarchical societies, particularly in societies that grew grain (an extremely monopolisable resource). For most of human history, however, most societies were egalitarian through "reverse dominance hierarchy" practices (Boehm, 1999) that were enabled by resources not being monopolisable (being more likely, dispersed, not defensible) by a group.

Morality also varies greatly according to these material conditions. The same conditions that give rise and maintenance to egalitarian practices also give rise to egalitarian moralities, while the conditions that give rise and maintenance to hierarchical practices also give rise to hierarchical moralities.

I think Nietzsche had a very valuable insight about morality reflecting the conditions of life (his "physiopsychology"), but the concept of morality of masters is much closer to Foucault's care of the self (expansion, life affirmation, art of living, aesthetics of existence) than practices of social domination (which include oppression, exploitation, marginalization, symbolic domination and so on, that can be seen as forces of conservation, decay and resentment). Furthermore, Nietzsche, in his time, could not have access to the anthropological and sociological knowledge that we have today.

By the way, thank you very much for your articles. Evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution bring great knowledge to complement Nietzsche.

Thanks for this super clear synthesis. My thought is that big states emerged as a byproduct of the switch-over from hunting/gathering food to growing it. Endless food = endless people. So war as an evolutionary mechanism was downstream from the population explosion, or a necessary outcome of plants peopling the earth so rapidly.