On the Hatred of the Behavioral Genetics of Intelligence

How our Christian heritage gave rise to a doctrine of radical equality

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights…

— from the Declaration of Independence

A couple months ago I witnessed the online mobbing of a PhD student named Emily Willoughby on Twitter. Let me give a sample of the insightful critiques leveled at her:

“Go to hell you racist bitch”

“… just don’t be a racist”

“You are… either a nazi or a complete ignorant.”

“It turns out this person is a nazi…”

“How well are the white supremacists paying you?”

“How could someone be so shitty to their core?”

Most of her critics declared that she was a racist, nazi, white supremacist, or something along those lines. What had she done to deserve this? She had committed the unforgivable crime of conducting mainstream research on the behavioral genetics of intelligence. None of her research has anything to do with race, of course, but that doesn’t matter. Anybody who suggests that intelligence is measurable and heritable can be declared a racist by default. The fact that an overwhelming mountain of evidence unequivocally demonstrates that intelligence is measurable and heritable is irrelevant. Facts are optional for these self-righteous defenders of justice and equality.

Behavioral genetics by itself is pretty controversial. Intelligence research is too. But their combination, the behavioral genetics of intelligence, incites this kind of moralistic self-righteousness more than almost any other subject in science. And not just on Twitter. The National Institutes of Health, for example, has essentially barred many researchers from using their data to study the genetics of intelligence (and related subjects like educational outcomes). The behavioral geneticist James Lee, in a recent article, reports that:

… the National Institutes of Health now withholds access to an important database if it thinks a scientist’s research may wander into forbidden territory… My colleagues at other universities and I have run into problems involving applications to study the relationships among intelligence, education, and health outcomes. Sometimes, NIH denies access to some of the attributes that I have just mentioned, on the grounds that studying their genetic basis is “stigmatizing.” (Lee, 2022)

Why is the NIH scared of this kind of research? Shouldn’t a scientific organization be in the business of pursuing the truth, regardless of the subject matter?

Steven Pinker, in his 2003 book The Blank Slate documents the historical opposition to the idea that biological differences contribute to differences in intelligence. He recounts some of this history within academia:

In 1974, Leon Kamin wrote that "there exist no data which should lead a prudent man to accept the hypothesis that IQ test scores are in any degree heritable”, a conclusion he reiterated with Lewontin and Rose a decade later. Even in the 1970s the argument was tortuous, but by the 1980s, it was desperate and today it is a historical curiosity. As usual, the attacks have not always come in dispassionate scholarly analyses. Thomas Bouchard, who directed the first large-scale study of twins reared apart, is one of the pioneers of the study of the genetics of personality. Campus activists at the University of Minnesota distributed handouts calling him a racist and linking him to "German fascism," spray-painted slogans calling him a Nazi, and demanded that he be fired. The psychologist Barry Mehler accused him of "rehabilitating" the work of Josef Mengele, the doctor who tormented twins in the Nazi death camps under the guise of research. (p. 378)

Again we see that those who study heritable individual differences — especially intelligence and related concepts — are smeared in the worst possible way (as racists, Nazis, etc.). Where does this hostility come from? That is the question I aim to address in this essay.

What I am not going to do in this essay is attempt to convince you that intelligence is measurable and heritable. Much ink has been spilled on that topic and others have done it far better than I could. See, for example:

Stuart Ritchie’s Intelligence: All That Matters

Richard Haier’s The Neuroscience of Intelligence

Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate

and for a more technical discussion, see Arthur Jensen’s The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability

As Pinker argued above, even by the 1980s, attempts to discredit the heritability of intelligence were “desperate”. These desperate attempts are still occasionally made today, but they are mostly ignored by those doing the actual research on the topic. IQ tests do a good job of measuring what most people mean by intelligence. They predict all the things we would want an intelligence test to predict (e.g., educational attainment, performance at complex jobs, and a variety of long-term life outcomes). And scores on IQ tests are highly heritable, with heritability increasing with age. These are all well-established scientific findings and I will treat them as such.

The question I am dealing with here is a different one: Why do some people hate this research so much that they will accuse those who conduct it of heinous moral crimes and attempt to bar the research from being conducted when they have the power to do so? And, by extension, why do these people seem to be so common among Western intellectuals?

Most people don’t have a problem with behavioral genetics. Lay people, when asked to estimate the heritability of intelligence, give an answer that is remarkably close to the average value in the scientific literature. Mothers of multiple children are especially good at estimating heritabilities. For most people, it seems natural to assume that people innately vary in their observable characteristics, and intelligence is just one among many traits that are like this.

It is mainly a select group of intellectuals (and budding intellectuals) who have a problem with the findings of behavioral genetics. I don’t think there are that many of them, but they are extremely vocal and can often be found at prestigious institutions. And it is clear that their problem is not primarily an empirical issue, but a moral one (given the ease with which they accuse those who conduct genetic research of heinous moral crimes).

In this essay I am going to put forward a somewhat counter-intuitive hypothesis: The hostility towards the behavioral genetics of intelligence has religious roots. Specifically, it is a consequence of the 2,000 year Christian heritage in the Western world. This is counter-intuitive because it is mainly secular intellectuals who have displayed the most hostility towards the subject. I believe that my hypothesis can explain this apparent disconnect.

In addition to explaining this particular phenomenon, this essay is also meant to be a demonstration of the method of genealogy more generally. I think that Friedrich Nietzsche was correct in asserting that we often have moral values without understanding the origins of these values. I think he was also correct in asserting that the only way to uncover the origins of these moral values is through a genealogy, i.e., a historical analysis of their origins. As a demonstration of this methodology, this essay is a historical analysis of the origins of the moral opposition to behavioral genetic research on intelligence.

I will structure the essay into the following claims:

Jonathan Haidt’s moral intuitionist model can explain how people can have moral intuitions without knowing why they have them or where they came from.

Moral intuitions among Western people have been profoundly shaped by the long history of Christianity in the West, and this remains true even among people who are now secular.

Christian theology equated moral equality with an equality of souls, and associated the soul with one’s capacity for reasoning/rationality (thus implicitly equating moral equality with equality of reasoning/rationality).

The loss of the belief in Christian metaphysics (e.g., the soul, the afterlife) while retaining Christian moral intuitions (about moral equality) made Western intellectuals particularly susceptible to a moral doctrine of radical equality (and by extension, particularly averse to any notion of natural inequality, e.g., natural inequality of intelligence).

1. The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement

Jonathan Haidt’s most highly cited scientific paper is his 2001 article “The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment”. In it he puts forward a new understanding of how moral judgements occur, in opposition to the rationalist models that have dominated psychology since at least the cognitive revolution. Rationalist models suggest that people reason their way into moral judgements through a process of rational reflection. Moral emotions, like sympathy and empathy, may have an influence on this reasoning process, but they do not directly cause moral judgements.

By contrast, Haidt suggests that moral judgements are primarily intuitive and automatic. Reason comes along after the fact in order to justify one’s intuitions to other people, but reasoning does not play much of a causal role in determining one’s moral judgements. Haidt’s model suggests that our reasoning capacity primarily plays the role of a lawyer or a press secretary. It does not make decisions for us (since our moral decision-making is primarily intuitive), but rather is used to persuade other people of the validity of our decisions, and potentially to bring them to our side of an issue.

How is it that we come to form these moral intuitions, if not through a process of conscious deliberation? Haidt has some relevant quotes that explain this process:

… moral intuitions are developed and shaped as children behave, imitate, and otherwise take part in the practices and custom complexes of their culture. (p. 828)

The social intuitionist model presents people as intensely social creatures whose moral judgments are strongly shaped by the judgments of those around them. (p. 828)

Moral development is primarily a matter of the maturation and cultural shaping of endogenous intuitions. People can acquire explicit prepositional knowledge about right and wrong in adulthood, but it is primarily through participation in custom complexes involving sensory, motor, and other forms of implicit knowledge shared with one's peers during the sensitive period of late childhood and adolescence that one comes to feel, physically and emotionally, the self-evident truth of moral propositions. (p. 828)

We come into the world equipped with a natural propensity for moral aversion and approval. Although there will be differences in what people find morally averse due to differences in temperament, there are some moral universals. This natural propensity becomes attuned to our own culture as we observe and imitate those around us during development, especially our peer group. Through this combination of innate instinct and enculturation we develop quick, automatic aversions to and approvals of certain kinds of behavior (i.e., moral intuitions). Later on, we will attempt to justify these moral intuitions with verbal reasons, but for the most part these verbal reasons are post-hoc constructions. Verbal reasons are how we explain our moral intuitions to other people, but they are not the true cause of our morality. Haidt’s model therefore repudiates rationalist models of moral development.

Although brilliant, Haidt’s model is not entirely original. In one of his early books Daybreak, Friedrich Nietzsche almost precisely summarized the social intuitionist model 120 years before Haidt published it. If one were to change the phrasing to reflect a modern style, Nietzsche’s account could have almost been written by Haidt:

It is clear that moral feelings are transmitted in this way: children observe in adults inclinations for and aversions to certain actions and, as born apes, imitate these inclinations and aversions; in later life they find themselves full of these acquired and well-exercised affects and consider it only decent to try to account for and justify them. This `accounting', however, has nothing to do with either the origin or the degree of intensity of the feeling: all one is doing is complying with the rule that, as a rational being, one has to have reasons for one's For and Against, and that they have to be adducible and acceptable reasons. To this extent the history of moral feelings is quite different from the history of moral concepts. The former are powerful before the action, the latter especially after the action in face of the need to pronounce upon it. (Daybreak, 34)

Haidt and Nietzsche’s understanding of morality tells us why we need a genealogy of morals. We simply cannot trust people’s stated reasons if we want to understand where moral judgements come from. Their stated reasons are only post-hoc justifications while the true reasons may be hidden from them. This is just as true for ourselves as it is for other people. Our own stated reasons (which we may fervently believe in) may also have little to do with the actual causes of our moral judgements. Only by tracing the history of a moral judgment can we understand it. That being said, genealogies are inherently uncertain. They are immune to the experimental method because we cannot do a re-run of history. Because they are not experiments, determining the causal arrow is inherently difficult. Nevertheless, the attempt must be made if we are to have any hope of understanding the origins of our own moral values.

In this case, I will trace the historical roots of the moral aversion to natural inequality among people, especially intellectual inequality.

2. The Long Shadow of Christianity

It is a peculiar fact that cultural changes can have long-lasting effects on a group of people’s moral and social norms, even long after those norms have ceased to serve their original purpose. For example, many groups impose restrictions on women that are designed to curb their sexuality. These restrictions can include dress codes, restrictions on who they can interact with, and even female genital mutilation (which functions to make sex less pleasurable). These restrictions are usually accompanied by more restrictive attitudes towards female sexuality among people in the group. Scientists have recently shown that groups with a history of pastoralism have more restrictive norms around female sexuality. This makes a lot of sense from an evolutionary perspective. One of the most evolutionarily detrimental situations for men is to unknowingly raise another man’s children (i.e., to be cuckolded). In pastoral societies, men are often away from home for long periods of time. Since men are also the primary economic providers, being cuckolded is a huge risk:

In pastoralism, men are not only frequently absent from camp, but they are also the ones providing the economic basis for their families. Hence, being absent – increased paternity uncertainty – is particularly costly for them. Consequently, they have a particularly pronounced incentive to control or restrict female sexuality in order to increase the likelihood that they are genetically related to their children. (Becker, 2019 p. 9)

What Becker goes on to show in this paper is that people with an ancestral history of pastoralism have more restrictive norms around female sexuality even if those people’s ancestors gave up their pastoral way of life many years ago. The norms stick around even after the stimulus that induced them is no longer relevant. Culture is “sticky” in this way. Cultural norms can exert effects for a long time after the stimulus that evoked the norm is no longer relevant.

Three recent books have made a similar case about the influence of Christianity on Western moral intuitions. These are:

Joseph Henrich’s 2019 The WEIRDest People in the World

Tom Holland’s 2019 Dominion

Larry Siedentop’s 2014 Inventing the Individual

These authors present evidence that the influence of Christianity is “sticky”. It can be found even after people have ceased to believe in Christian propositions (about the existence of God, the resurrection, etc.). In all three books, the authors argue that Christianity has exerted a large influence on the Western psyche, even (and perhaps especially) among secular people. In my experience, many secular people, especially those who consider themselves atheists, do not like this idea. They tend to believe (in the spirit of Sam Harris) that their morality is the result of rational reflection. The idea that their morality has anything to do with Christianity, which they repudiate as dogmatic nonsense, is anathema. The evidence, however, tells a different story.

In his 2019 book The WEIRDest People in the World, Joseph Henrich presents evidence that Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic (WEIRD) people have some peculiar psychological traits that make them stand out in relation to the rest of the world. Some of the traits that make WEIRD people different consist of being relatively individualistic, nonconforming, patient, trusting, and focused on intentions in moral judgements. In his book, Henrich attributes Western WEIRDness primarily to the influence of Christianity, and especially the “marriage and family program” (MFP) of the Catholic church (e.g., restrictions on cousin marriage, enforcement of monogamy, etc.). Henrich’s argument is complex and I won’t rehash it here. Instead, what I want to focus on is the empirical evidence presented that an area’s exposure to the Catholic church is a strong predictor of that area’s WEIRDness today. Henrich states:

National populations that collectively experienced longer durations under the Western Church tend to be (A) less tightly bound by norms, (B) less conformist, (C) less enamored with tradition, (D) more individualistic, (E) less distrustful of strangers, (F) stronger on universalistic morality, (G) more cooperative in new groups with strangers, (H) more responsive to third-party punishment (greater contributions in the PGG with punishment), (I) more inclined to voluntarily donate blood, (J) more impersonally honest (toward faceless institutions), (K) less inclined to accumulate parking tickets under diplomatic immunity, and (L) more analytically minded. These effects are large. (p. 227)

A history of exposure to Christianity is correlated with a variety of psychological/behavioral outcomes. These differences are not trivial. For example, one millennium of exposure to the MFP is associated with a 30 percentile drop in conformity on the Asche conformity test (in which people are asked questions with obvious answers to see if they will conform with the answers of those around them). A millennium of exposure to the MFP also increases people’s propensity to donate blood (a form of impersonal prosociality) by a factor of five. Although these correlations cannot directly tell us about the causal basis underlying them, the sheer size of these effects indicates that something is having a major effect on these populations.

Importantly, these effects are just as strong in countries that have become more secular. WEIRD morality (i.e., individualism, universalism, impersonal prosocial norms) is predicted by a history of Christian influence but does not rely on Christian beliefs.

Two peculiar aspects of WEIRD morality are its focus on the individual (e.g., that individuals have inalienable rights) and its universality (e.g., the idea that moral norms apply equally to kings and peasants). I suspect it is hard for many Western people to imagine just how historically peculiar these moral precepts really are. For most of human history, the family was the fundamental moral unit and not the individual. It was perfectly reasonable, for example, to punish a father for the crimes of his son (or cousin, or whatever). As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz put it:

The Western conception of the person as a bounded, unique, more or less integrated motivational and cognitive universe; a dynamic center of awareness, emotion, judgment, and action organized into a distinctive whole and set contrastively both against other such wholes and against a social and natural background is, however incorrigible it may seem to us, a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world’s cultures. (1974, p. 31)

In other words, the Western conception of the individual as being relatively separate from his social and cultural context is peculiar. It probably developed in part because of the Catholic church’s marriage and family program, as was hypothesized by Henrich (though I suspect that there is more to the story, as I will discuss below).

WEIRD universalism is related to this individualism. We tend to think that the same rules apply to everyone, regardless of their status, sex, etc. Again, this is very peculiar in the context of human history more generally. For most of human history, commoners had very different rules to live by than nobles. This is as true of the Indian caste system as it is of the hierarchies of the ancient Greeks and Romans. The idea that a king was in any sense morally equivalent to a slave would have been laughable to them.

This was also more or less true for much of the history of Christianity, but the idea of moral equality was always festering in the background, eventually erupting in the protestant revolution (which equalized access to God) and in the conversions to democratic forms of government across the Western world. This is why the writers of the declaration of independence could unironically state that it was self-evident that all men are created equal. The idea that men were created equal would, again, have been laughable to the average Greek or Roman citizen. Even to us, it is mostly obvious that people are not equal on any observable dimension (athleticism, charisma, attractiveness, etc.). But for the authors of the declaration, it was moral equality that they were concerned with. People are equal before God, if not on earth. That people are morally equal was definitely not self-evident to our more ancient ancestors. Where did this self-evident moral equality come from?

3. The Equality of Souls

The historian Tom Holland argues that the idea of moral equality is inherent in the story of Jesus Christ, and most especially in the idea of a god (even the God) on a cross. In order to understand the impact of Christianity on the Western world, we must understand just how radical the story of Christ was in the context of the Roman world in which it emerged. For the Romans, death by crucifixion was a punishment usually reserved for disobedient slaves. It was considered one of the worst possible ways to die. Holland (2019) describes it as such:

Exposed to public view like slabs of meat hung from a market stall, troublesome slaves were nailed to crosses… To be hung naked, ‘long in agony, swelling with ugly weals on shoulders and chest’, helpless to beat away the clamorous birds: such a fate, Roman intellectuals agreed, was the worst imaginable. This in turn was what rendered it so suitable a punishment for slaves. (p. 2)

Conversely, the Roman gods were powerful entities, capable of inflicting suffering on their enemies. They were not victims of unfair treatment. For the Romans, divinity was intimately tied up with power. Those with more power were closer to divinity than those with less power. The idea that somebody with the kind of divine power attributed to a god would allow themselves to be strung up and tortured was ridiculous. Holland states:

Divinity, then, was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings. Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque. (p. 6)

It is against this backdrop that we must understand the effect that the Christian mythos had on the Western world. The god on a cross was a radical symbol that effectively inverted the morality of the Greeks and Romans. That a man from humble origins, condemned to a death reserved for disobedient slaves, might have been a manifestation of God sent a clear message to those who believed in it: Divinity and power are not equivalent. Paul of Tarsus eventually made this message more explicit in his letter to the Corinthians:

… God has chosen the foolish things of the world to shame the wise, and God has chosen the weak things of the world to shame the things which are strong, and the insignificant things of the world and the despised God has chosen, the things that are not, so that He may nullify the things that are, so that no human may boast before God. (Corinthians 1:27-29)

Again, we must recognize how radical this statement is in the context of the Roman world in which it emerged. Larry Siedentop, in his 2014 book Inventing the Individual describes how the Romans and Greeks perceived hierarchy in the world:

At the core of ancient thinking we have found the assumption of natural inequality. Whether in the domestic sphere, in public life or when contemplating the cosmos, Greeks and Romans did not see anything like a level playing field. Rather, they instinctively saw a hierarchy or pyramid. Different levels of social status reflected inherent differences of being[…] so entrenched was this vision of hierarchy that the processes of the physical world were also understood in terms of graduated essences and purposes – ‘the music of the spheres’. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 51)

He goes on to describe how Paul’s understanding of the Christ narrative overturned this hierarchical way of thinking:

Paul’s conception of the Christ overturns the assumption on which ancient thinking had hitherto rested, the assumption of natural inequality. Instead, Paul wagers on human equality. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 60)

A fundamental reversal of assumptions had taken place. Justice was no longer understood in terms of natural inequality, but rather of natural equality. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 205)

This reversal of ideas about justice will prove to be incredibly important in the following millenia. It will underlie the new-found assumptions of universal human rights and democratic governance. Tom Holland similarly describes how the Christian narrative was overturning assumptions about natural hierarchy:

Age-old presumptions were being decisively overturned: that custom was the ultimate authority; that the great were owed a different justice from the humble; that inequality was something natural, to be taken for granted. (Holland, 2019 p. 238)

Larry Siedentop suggests that Christianity put an especially important emphasis on the equality of souls. Although people may differ in their earthly characteristics and relations, the Christian ethos is that we are all equal before God. We may have social roles that make us unequal (e.g., the relation between a father and his children), but these identities are secondary to our true identity as equal children of God.

For Paul, belief in the Christ makes possible the emergence of a primary role shared equally by all (‘the equality of souls’), while conventional social roles – whether of father, daughter, official, priest or slave – become secondary in relation to that primary role. To this primary role an indefinite number of social roles may or may not be added as the attributes of a subject, but they no longer define the subject. That is the freedom which Paul’s conception of the Christ introduces into human identity. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 62)

What must be understood about this new-found moral assumption of equality is that it was a reaction to the oppression of the Romans and was therefore a reaction to Roman morality (which was heavily influenced by its Greek heritage). In part 2 of my “Revaluation of All Values” series I detailed the many ways in which Christian morality inverted the Homeric Roman/Greek morality. I won’t belabor the point here. Here I only want to make the point that Christianity took on some of the assumptions of Roman/Greek morality only in order to invert them. One of these assumptions was the association of reason with the divine soul. Reason (i.e., the capacity for rational contemplation and argumentation) took on an outsized role in Athenian and Roman life because of their democratic organization. As Siedentop put it:

Reason or rationality – logos, the power of words – became closely identified with the public sphere, with speaking in the assembly and with the political role of a superior class. Reason became the attribute of a class that commanded. At times reason was almost categorically fused with social superiority. (Siedentop, 2014 p. 35)

As Siedentop suggests, reasoning capacity and superiority (of power) were closely intertwined in Greek and Roman life. This shouldn’t be surprising. One’s capacity for rational decision-making and argumentation is a legitimate reason to be given more power and influence, especially in a democracy. People naturally defer to those with good decision-making abilities (and as I discussed in a previous essay, this has probably been true throughout most of human evolutionary history). Thus, reason/rationality’s association with power in the Greek and Roman world is unsurprising.

The elevation of reason among Greek philosophers reflected its importance in democratic life. Plato, for example, made it clear that reason was associated with divinity. As Jonathan Haidt put it:

Philosophers have frequently written about the conflict between reason and emotion as a conflict between divinity and animality. Plato's Timaeus (4th century B.C./1949) presents a charming myth in which the gods first created human heads, with their divine cargo of reason, and then found themselves forced to create seething, passionate bodies to help the heads move around in the world. The drama of human moral life was the struggle of the heads to control the bodies by channeling the bodies' passions toward virtuous ends. (Haidt, 2001 p. 815)

Plato’s association of reason with divinity is important because his writings had an outsized influence on early Christianity. As the theologian William Inge wrote:

Platonism is part of the vital structure of Christian theology . . . . [If people would read Plotinus, who worked to reconcile Platonism with Scripture,] they would understand better the real continuity between the old culture and the new religion, and they might realize the utter impossibility of excising Platonism from Christianity without tearing Christianity to pieces. (quoted here)

Now we are beginning to see how reasoning capacity came to be associated with moral equality. Tom Holland makes the connection explicit in contending that, in Christianity, “every human being had been made equally by God and endowed by him with the same spark of reason.” (Holland, 2019 p. 347)

That “spark of reason” was intimately tied up with notions of moral equality. The connection of ideas goes something like this, in the form of a syllogism:

If divine soul = reasoning capacity

And moral equality = equality of souls

Then moral equality = equality of reasoning capacity

And there we have a sketch of my basic argument. The association between reasoning capacity and moral equality is deeply ingrained in the Western psyche. If you suggest that people naturally differ in their capacity for reasoning and/or rational agency, you are directly attacking the underlying assumptions inherent to the idea of moral equality. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t think that the reasons above (e.g., the syllogistic argument about moral equality) are the cause of Christian moral intuitions. Rather, tracking the reasons is simply a way of tracking how those moral intuitions have developed over time. The actual causes are much more complicated (and likely involve cultural evolutionary processes that I described in the first part of my “Revaluation” series).

The ancient vision of a moral hierarchy was predicated on the idea that some humans were more endowed with reason than others. The new vision of moral equality was predicated on the idea that all humans were endowed with the capacity for rational agency. Siedentop makes this explicit:

Today when we see other humans, we see them first of all as individuals with rights… That is, we now see humans as rational agents whose ability to reason and choose makes it right to attribute to them an underlying equality of status, a moral equality. We are even inclined to see this moral equality as a fact of perception rather than a social valuation, so ingrained is our assumption that rational agency demands equal concern and respect. (Siedentop, 2014 pp. 13-14)

As demonstrated in the opening quotation, it is self-evident to many Westerners that people are created equal. The historical oddity of this statement cannot be overstated. For the majority of people throughout human history, it was self-evident that people were not equal. For Aristotle, for example, it was self-evident that slaves and women lacked the reasoning capacity inherent to citizens (i.e., adult, Greek, property-holding men).

The behavioral genetics of intelligence suggests that people are not equally endowed with the capacity for rational agency (although contra Aristotle, there is no real difference in IQ between men and women). Thus, the behavioral genetics of intelligence is implicitly seen as a challenge to moral equality. This is why it generates such strong reactions from people. We can surmise, however, that the findings of behavioral genetics would have been of no consequence at all to a Greek citizen or a Roman noble. They would have been totally unsurprised that people differ in their reasoning capacity. When they looked at the world, they naturally saw it as hierarchical, and this was as true for how they viewed people as for anything else. It is mainly WEIRD people, and their individualistic/universalistic moral assumptions, for whom the idea of natural inequality poses a moral threat.

Interestingly, behavioral genetics does not generate equally strong reactions from all people. It’s obvious that the most fanatical opposition to the behavioral genetics of intelligence (and other scientific findings that indicate natural inequalities) comes from secular left-wing intellectuals.

This may seem strange in light of the analysis I have just put forward. If the aversion to natural inequality stems from our history of Christianity, shouldn’t those who have moved furthest away from Christian beliefs be the most immune to its influence? Not so. In fact, I will argue that it is precisely because Western intellectuals have lost their Christian beliefs that their insistence on equality is so fervent.

4. The Vision of the Elect

Why can’t they allow other views? Remember, this is religion, not political science, and specifically a religion eerily akin to devout Christianity. (McWhorter, 2020 p. 47)

In the quotation above from John McWhorter’s recent book Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America, he is describing what he believes is literally a new religion emerging among the intelligentsia (mainly academics, journalists, and the political class). At the core of this new religion is a particular ethos, which McWhorter suggests goes something like this:

Battling power relations and their discriminatory effects must be the central focus of all human endeavor, be it intellectual, moral, civic, or artistic. Those who resist this focus, or even evidence insufficient adherence to it, must be sharply condemned, deprived of influence, and ostracized. (p. 11)

What does it mean to ‘battle power relations’? By power relations, he is referring to the unequal distribution of power. The central value of the new religion is therefore equality. Not necessarily moral equality (as the founding fathers were referring to in the declaration of independence), but equality of power.

Interestingly, McWhorter suggests that the new religion is “eerily akin to devout Christianity”. He is not the first to notice this connection. McWhorter calls the members of this new religion “the Elect”. He describes the fervor of the Elect as such:

The Elect consider it imperative to not only critique those who disagree with their creed, but to seek their punishment and elimination to whatever degree real-life conditions can accommodate. There is an overriding sense that unbelievers must be not just spoken out against, but called out, isolated, and banned…

The reality is that what the Elect call problematic is what a Christian means by blasphemous. The Elect do not ban people out of temper; they do it calmly, between sips of coffee as they surf Twitter, because they consider it a higher wisdom to burn witches. Not literally, but the sentiment is the same. The Elect are members of a religion, of a kind within which the dissenter is not just someone in disagreement but is a kind of environmental pollution. (McWhorter, 2020 pp. 43-44)

As we saw in the opening example with Emily Willoughby (who is only one of many who have been attacked by the Elect for studying the wrong subject), blasphemy is met with harsh condemnation. I think McWhorter is right to call this ideology a religion. With the exception of supernatural beliefs, it has all the trappings of a religion and its adherents show the same fervor and dogmatism we have come to expect from religious fanatics. McWhorter is wrong, however, to suggest that this religion is something new. McWhorter mistakes superficial changes in vocabulary and beliefs with the emergence of an entirely new worldview. To the contrary, the modern tenets of the Elect are simply permutations of an older worldview, described by Thomas Sowell in his 1995 book The Vision of the Anointed. Those who McWhorter calls the Elect are the intellectual descendants of those who Sowell calls the Anointed.

In both cases, McWhorter and Sowell are referring to people in academia, journalism, law, and politics with a very particular worldview, who treat their detractors not as opponents to be debated but as heretics to be morally condemned. Sowell argues that the vision of the anointed emerged about 200 years ago at the end of the 18th century. It is no coincidence that this coincides with the beginning of the decline of Christian beliefs among Western intellectuals.

At the heart of the vision of the anointed is the presumption that they have superior wisdom and virtue while their detractors are morally tainted, stupid, or both. This is why they don’t really need arguments or facts (though they will selectively call upon them when necessary). They can just call you a racist (or any other relevant insult; classist, sexist, transphobe, nazi, etc.) and be done with it. In the context of the behavioral genetics of intelligence, the fact that you would even consider natural differences in intelligence a worthwhile subject to look into is evidence enough of your moral perversion.

Sowell contrasts the vision of the anointed with the tragic vision. I am going to take some liberties in describing these contrasting visions. My description will be a little different from Sowell’s, but this is mainly because we are focused on different issues. Sowell was focused on public policy while I am focused on empirical beliefs. If you are familiar with Sowell’s work I suspect you will agree that my differences in description do not contradict his, but are simply differences in emphasis.

The vision of the anointed goes something like this:

All humans are basically equal (if given equal circumstances)

All humans are basically good (if given good circumstances)

All social ills are due to unequal/bad circumstances (given the right circumstances, all people will flourish)

It is our job to make circumstances better and more equal

Then we will bring about the kingdom of God on earth

Ok, 5 is meant to be tongue-in-cheek, but the point is that the vision of the anointed is implicitly or explicitly utopian. If only we can enact the right policies, they seem to think, then we will put an end to crime, poverty, and inequality once and for all. As Sowell repeatedly demonstrates, the anointed think that there are solutions to perennial problems. In reality, there are only trade-offs. Compare this to the tragic vision, which goes something like this:

Humans are not equal (and any attempt to make them so will be an authoritarian nightmare)

Humans are not basically good (pretending otherwise is naive and will lead to bad policy)

Social ills may or may not be due to bad policy (some social ills are perennial and the misguided attempt to eradicate them will be worse than the illness)

There are no solutions to social problems, only trade-offs (messing with complex systems always has unintended consequences)

Utopia is not for this world

Each of these visions is more complicated than my descriptions of them, so I regard these as useful simplifications. In the tragic vision, the line between good and evil runs through the heart of every man (as Solzhenitsyn put it). In the vision of the anointed, we are the good, just, and wise, and they (the unwashed masses) are the ignorant and/or evil people getting in our way. If only they would get out of the way so we could enact our preferred policies, we could eliminate all the injustices of the world (or so the Elect seem to think).

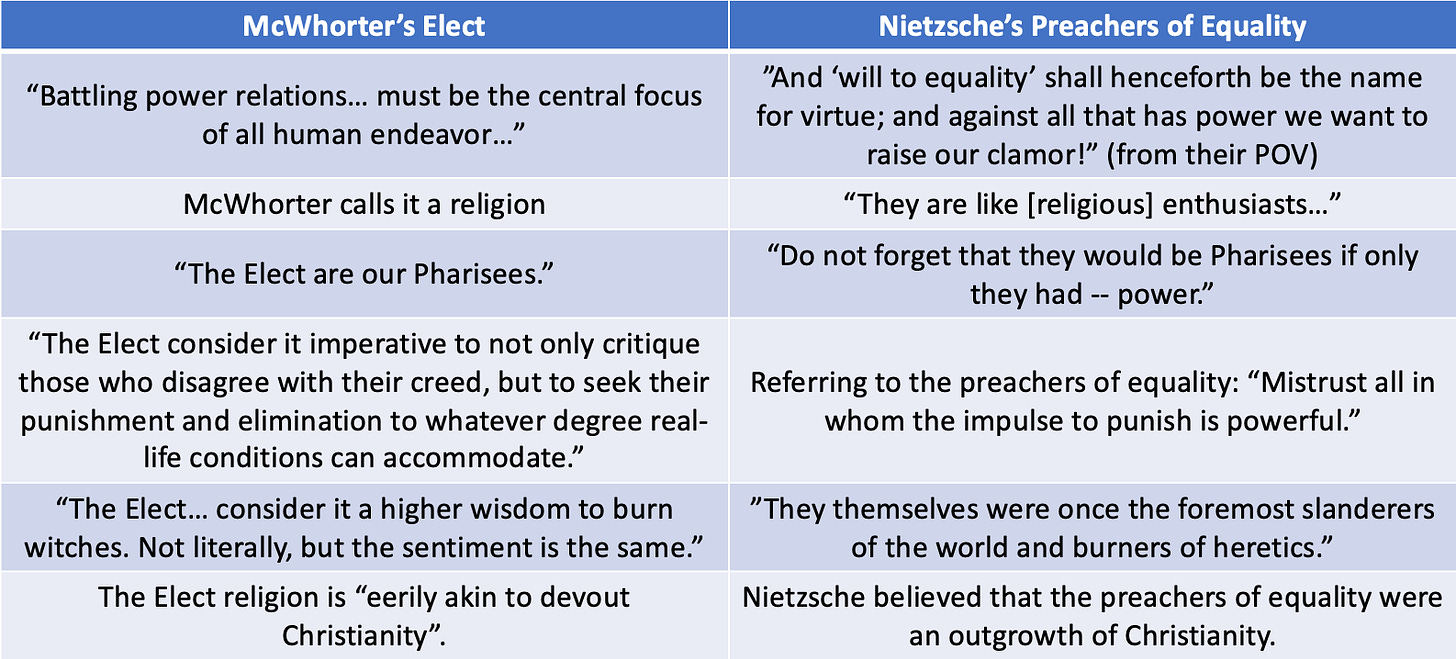

Much earlier than McWhorter and Sowell, the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was describing those whom he referred to as “the preachers of equality” and “the good and the just”. My contention is that Nietzsche’s “preachers of equality” are the exact same kind of person being described by McWhorter and Sowell. The overlaps between Nietzsche’s description of the preachers of equality and McWhorter’s description of the Elect are uncanny. These overlaps are described in the table below:

The particular ideas have changed over the years, but the underlying ethos has remained the same, as demonstrated by the overlap between Nietzsche’s description (written in the late 19th century) and McWhorter’s (written around 2020). Interestingly, Nietzsche (in concert with Thomas Sowell) also describes his own vision as “tragic” in contrast to the preachers of equality. My contention is that McWhorter, Sowell, and Nietzsche are all describing the same phenomenon but using different vocabulary. For the purposes of this essay I will mainly use McWhorter’s language (the Elect) since his is the most recent and intuitive.

According to Sowell, the vision of the Elect emerged in the late 18th century, which coincides with the time period that Christianity was losing its influence among the intelligentsia. This is no coincidence. I believe, as Nietzsche did, that the vision of the Elect is an outgrowth of Christianity. To put it simply, Electism is what can happen when people with Christian moral intuitions lose their belief in Christian metaphysics.

As described by Siedentop and Holland, Christianity put forward a particular vision of justice and equality. Although injustice may reign today, justice would be had after the resurrection, when God separates the sinners from the believers.

They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away… Those who are victorious will inherit all this, and I will be their God and they will be my children. But the cowardly, the unbelieving, the vile, the murderers, the sexually immoral, those who practice magic arts, the idolaters and all liars—they will be consigned to the fiery lake of burning sulfur. (Revelation 21)

The Christians will have their justice. Maybe not in this life, but at least in the next. Similarly, if you believe in an immortal soul then empirical findings about natural inequality are totally irrelevant to the assumption of moral equality. As the bioethicist Erik Parens put it:

The idea of moral equality has deep roots in Western religious traditions, which teach that human beings are equal before God. If you think that the moral equality of humans derives from the existence of a God-given immortal soul, then what behavioral genetics has to say is utterly irrelevant to moral equality. (2004, pp. 27-28)

This is true. Even if there is an implicit association between reasoning capacity and moral equality, that association will be tempered if you also believe in the existence of an immortal, immaterial soul. But what if you no longer believe in the resurrection, where God will mete out justice at the end of time? And what if you no longer believe in the immortal, immaterial soul? What if you no longer believe these things but you still believe, deep in your bones, in the value of justice and equality? In this case, justice cannot be reserved for some future promised world. Justice must be had here and now. Similarly, the equality of souls must be replaced with substantial equality here on earth (and the assumption of equal reasoning capacity will therefore become more important). And here we have the birth of what Thomas Sowell calls the pursuit of “cosmic justice”, which is central to the vision of the Elect:

In a sense, proponents of "social justice" are unduly modest. What they are seeking to correct are not merely the deficiencies of society, but of the cosmos. What they call social justice encompasses far more than any given society is causally responsible for. Crusaders for social justice seek to correct not merely the sins of man but the oversights of God or the accidents of history. What they are really seeking is a universe tailor-made to their vision of equality. They are seeking cosmic justice. (Sowell, from a speech on cosmic justice)

The pursuit of cosmic justice is the pursuit of perfect justice and equality here and now. What must be understood about this, however, is that the Elect do not use the words justice and equality in the same way that everyone else uses those words. For the average person, justice is had when everyone is made to play by the same rules. When the process works the same for every person there is justice. Thus, many people feel that justice is violated when Harvard university uses a different set of rules for people of different racial groups in its admission standards (meaning that an Asian American must meet much higher standards than other people in order to get into Harvard). To the Elect, however, it would be unjust if there were a disproportionate number of Asian and white people at Harvard, regardless of the standards used for admission. Most people are concerned about processes. The Elect are concerned about outcomes. This is the fundamental difference between traditional justice and cosmic justice.

My contention is that the pursuit of cosmic justice is what can happen when people with Christian moral intuitions lose their belief in Christian metaphysics. This is the origin of the Elect. This is why the ideology is so common among secular intellectuals. It is for this group that the “death of God” (i.e., the loss of belief in Christian metaphysics) has been the most complete. Nietzsche began to see this transformation in his own time. In The Twilight of the Idols he said that:

They are rid of the Christian God and now believe all the more firmly that they must cling to Christian morality… When the English actually believe that they know “intuitively” what is good and evil, when they therefore suppose that they no longer require Christianity as the guarantee of morality, we merely witness the effects of the dominion of the Christian value judgment and an expression of the strength and depth of this dominion: such that the origin of English morality has been forgotten, such that the very conditional character of its right to existence is no longer felt. (TI, Skirmishes of an Untimely Man 5)

Here Nietzsche is mainly referring to people like Jeremy Bentham who believe that their utilitarian morality is “self-evident” (though really it is a mask for Christian moral intuitions). But his point is that the loss of Christian belief did not necessitate the loss of Christian morality. In his book The Antichrist, Nietzsche makes clear that the “preachers of equality” emerged from Christian morality.

And let us not underestimate the calamity which crept out of Christianity into politics. Today nobody has the courage any longer for privileges, for masters’ rights, for a sense of respect for oneself and one’s peers —for a pathos of distance. Our politics is sick from this lack of courage.

The aristocratic outlook was undermined from the deepest underworld through the lie of the equality of souls; and if faith in the “prerogative of the majority” makes and will make revolutions—it is Christianity, beyond a doubt, it is Christian value judgments, that every revolution simply translates into blood and crime. (Antichrist 43)

I have my disagreements with Nietzsche about Christianity (at some point I will write an essay detailing what I believe to be the central truth within the Christian ethos), but on this point I think he is as prescient as usual. Christian value judgements (i.e., moral intuitions) represented by the idea of an “equality of souls” underlaid the ideology of equality that was coming to the fore in Nietzsche’s time, and which has now completely overtaken intellectual life. And since the soul was implicitly associated with “reason”, the behavioral genetics of intelligence keeps producing stubborn facts that are anathema to this ideology. The bioethicist Erik Parens mentioned above nicely summarizes the moral opposition to this research.

… by investigating the causes of human differences, people worry, behavioral genetics will undermine our concept of moral equality… Unfortunately, there is an old and perhaps permanent danger that inquiries into the genetic differences among us will be appropriated to justify inequalities in the distribution of social power. (2004, p. 31)

The evolution of ideas which led to this kind of reasoning might be summed up like this:

Christian moral intuitions + Christian metaphysics = justice (in the afterlife) and equality (of souls)

Christian moral intuitions - Christian metaphysics = justice (here and now) and equality (of outcomes rather than processes)

Justice and equality (as outcomes rather than processes) = the vision of the Elect

What is important to understand about the vision of the Elect — and what Sowell goes to great lengths to demonstrate — is that, in judging the validity of their vision, evidence is irrelevant. Their vision, whatever it may be, is simply immune to any amount of evidence against it. And this is what we see in the realm of intelligence research and behavioral genetics. The evidence that intelligence is highly heritable is overwhelming. The Elect, however, will go to great lengths to deny that this evidence is evidence, mostly by accusing its purveyors of moral perversions of one kind or another (usually by calling them racists or some other term of abuse). When they have the power to do so, the Elect will simply not allow the evidence to be collected at all, as they have done at the NIH (as described by James Lee in the introduction). They will, of course, make some arguments in their favor, but these arguments are uniformly “tortuous” and “desperate” as Pinker described them. What must be understood is that, for the Elect, natural equality is not a scientific question to be debated, but a moral necessity to be asserted without regard for the evidence.

In fact, the kind of cosmic justice that the Elect seek is only attainable if people are basically equal by nature and basically good by nature. This is because the vision of the Elect only works if inequality and human suffering can be attributed to “society” rather than nature. For the Elect, human nature is relatively unconstrained and can be changed and adapted so that desired outcomes can be achieved, if only those ignorant and/or evil detractors would get out of the way. By positing that people naturally differ in their potential and talents, you are saying that society is not the cause of all inequality. This is unacceptable to the Elect.

By contradicting natural equality, you are therefore implicitly contradicting their vision of cosmic justice. And they will do anything to protect that vision. This is why, even though the behavioral geneticist Kathryn Harden shares the vision of cosmic justice inherent to the Elect, her recent book The Genetic Lottery was still smeared by some reviewers as being overly simplistic and, yes, even “racist”. Harden is a smart scientist who was confronted with the overwhelming evidence for genetically caused differences in intelligence (and other socially desirable traits). Her book represents the (misguided) attempt to maintain the vision of the Elect (i.e., the pursuit of cosmic justice) in the face of this evidence. Despite her adherence to the values of the Elect, and despite the fact that her book has nothing to do with race (except insofar as she makes sure to mouth the right shibboleths about racism), she was still smeared as a racist because she dared to posit the existence of natural intellectual inequality. Natural inequality is incompatible with the vision of the Elect, even if Harden doesn’t realize it.

To address the political elephant in the room, the vision of the Elect is clearly associated with the political left. But it is far from identical to it. There are plenty of people who identify with the political left (or liberalism in the United States) who do not actively try to punish, censor, and exclude anyone with a different worldview. By the Elect, I am only referring to those with a particular vision of the world within which it makes sense for them to shut down dialogue or scientific inquiry that violates their moral assumptions.

Once upon a time it was Christian fundamentalists who posed the greatest threat to the scientific enterprise. They lost that culture war, and thank God (sic) for that. Today a different kind of fundamentalism poses a far greater threat because it comes from within the academy.

The censors and gatekeepers simply assume—without evidence—that human population research is malign and must be shut down. The costs of this kind of censorship, both self-imposed and ideologically based, are profound. Student learning is impaired and important research is never done. The dangers of closing off so many avenues of inquiry is that science itself becomes an extension of ideology and is no longer an endeavor predicated on pursuing knowledge and truth. (Maroja, 2022)

These preachers of equality would bar any research that violated their moral precepts if they could get away with it. This is obviously the case, because when they can get away with it, this is exactly what they do. And this is what is so important to understand. Time and again, the Elect have demonstrated that they will do whatever they can get away with in the service of their moral vision.

Conclusion: The Religion of Revenge

O my brothers, who represents the greatest danger for all of man’s future? Is it not the good and the just? Inasmuch as they say and feel in their hearts, “We already know what is good and just, and we have it too; woe unto those who still seek here!” And whatever harm the evil may do, the harm done by the good is the most harmful harm. And whatever harm those do who slander the world, the harm done by the good is the most harmful harm. (Nietzsche, Zarathustra, III. 12. 26)

Not every ideology appeals to every person. Behavioral genetic research has shown that ideological stances are themselves a heritable trait. Some people will find the religion of the Elect more appealing than others, just as some more than others found Trump to be an appealing presidential candidate. A full analysis of the psychology of the Elect will have to be reserved for another time, but here I want to conclude by briefly describing what Nietzsche believed motivated the preachers of equality.

McWhorter and Sowell describe the behavior of the Elect but they do not do much by way of a psychological analysis. Nietzsche, however, was clear about what he believed to be the underlying psychological motivation of those who were most drawn to the ideology of equality. Time and again throughout history, the attempt has been made to sanctify the desire for revenge as the desire for justice. The anti-semites want justice (but they really mean revenge against the Jews). The anarchists want justice (but they really mean revenge against the powerful). And today too, the Elect say that they want justice. In his 2022 book The War On the West, Douglas Murray suggests that they too (at least the most devout among them) are really after revenge. They, too, disguise this desire for revenge with noble-sounding words like “equality” and “justice”.

… just as the men of resentment talk about “justice” while meaning “revenge,” so it is that something is disguised within their talk of “equality.” For anyone who talks of “equality” will find an inbuilt problem. Only a person who “fears he will lose” will demand equality as a “universal principle.” It is a speculation [on a falling market]…

For all talk of “equality,” like the talk of “justice,” presents itself in one light—not least a disinterested light, as though its proponents only want an abstract thing and hardly notice whether or not this thing will ever benefit themselves. But very often it is no such thing. A set of far more fundamental issues are working themselves out[…] For just as we are not up against justice but rather up against vengeance, so we are not truly up only against proponents of equality but also against those who hold a pathological desire for destruction. (p. 206)

This interpretation may seem like it is profoundly uncharitable. But when I observe the glee that these preachers of equality exhibit when they have found a new victim to slander, I don’t see embodiments of justice, love, or wisdom (as they would like you to see). I see what Nietzsche saw: resentment and revenge disguised as morality.

What I see are people who will inflict precisely as much suffering upon their victims (i.e., the heretics like Emily Willoughby) as they have the means to inflict. If they can get you fired, they will do that. If they can get your license for practicing your profession taken away, they will do that. If they can use lies and slander to make you a social pariah, they will do that. They have demonstrated their propensity for punishing heretics over and over again. And if they had more power, they would do more. They are limited by their means, not by their resolve. The only reason they don’t burn you is because they can’t get away with it.

I want to be clear that I do not believe that all or even most of the Elect are primarily motivated by resentment and revenge. Most are simply motivated by careerism and conformity (since giving lip service to the new religion will pay dividends in academia and mainstream journalism; the whole purpose of “diversity statements” in academia is to exclude heretics). Some of the Elect are highly agreeable people who have been convinced that this view of things is the “compassionate” way of viewing the world. In my experience, this latter type is the most apt to leave the faith when they realize that the compassion of the Elect is often a mask for less noble motivations (see, e.g., the intellectual journey of YouTuber Laci Green). In other words, most of the Elect are just regular people who have been drawn to the ideology because of either social incentives or its surface-level compassionate stance.

But at the core of the new religion are a small number of true believers; the ones who are the most censorious and venomous in their attacks on heretics. Although these true believers would like to represent themselves as embodiments of wisdom and virtue, I see something different.

What do they really want? At least to represent justice, love, wisdom, superiority—that is the ambition of the “lowest,” the sick. And how skillfull such an ambition makes them! Admire above all the forger’s skill with which the stamp of virtue, even the ring, the golden-sounding ring of virtue, is here counterfeited. They monopolize virtue, these weak, hopelessly sick people, there is no doubt of it: “we alone are the good and just,” they say, “we alone are [men of good will].” They walk among us as embodied reproaches, as warnings to us—as if health, well-constitutedness, strength, pride, and the sense of power were in themselves necessarily vicious things for which one must pay some day, and pay bitterly: how ready they themselves are at bottom to make one pay; how they crave to be hangmen. There is among them an abundance of the vengeful disguised as judges, who constantly bear the word “justice” in their mouths like poisonous spittle… (Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals, III. 14)

Against whom do they seek vengeance? Against anyone with “health, well-constitutedness, strength, pride, and a sense of power”. In other words, anyone who is not a victim.

We shall wreak vengeance and abuse on all whose equals we are not. Thus do the tarantula hearts vow. (Zarathustra, I. 12)

But they call that justice.

In my opinion the scientific enterprise is the greatest achievement of Western culture. I fear for its longevity and integrity. From within the academy, there is now “an existential threat to doing good science” as Luana Moroja recently put it. The enemies of open scientific inquiry have gained a foothold in our institutions, including some of the most prestigious scientific organizations such as the journal Nature and the NIH.

The unpleasant reality that we must face today is that there is a small subset of intolerant ideologues who oppose open discourse altogether[…] This fanatical minority is tiny in size but has successfully cowed university administrators, corporate leaders, and large swathes of thoughtful people into silence. They have even created climates of fear in institutions that were established with the explicit purpose of defending free thought. (Lehmann, 2020 p. 217)

I do think that the true believers are a small minority. We have allowed these hopelessly weak, resentful, vengeful individuals to exercise an outsized amount of influence on the scientific enterprise. We have done this for multiple reasons, but mostly out of fear of being labeled all of the most terrible things if we resist: racist, sexist, transphobic, etc. This fear is not unfounded. To be labeled these things in our culture is to risk losing your job (or future career prospects) and your social standing.

Some believe that the Elect have good intentions, but are only misguided in their methods. Although their attempts to punish and silence everyone who disagrees with them may be misguided, some charitable individuals will suggest that the Elect are “well-intentioned” in their pursuit of justice and equality. I think that people who believe that must be terribly naive. The fact that someone presents themselves in a self-righteous light is no evidence of their actual righteousness. I think we should all take Nietzsche’s advice, to:

Mistrust all in whom the impulse to punish is powerful. They are people of a low sort and stock. The hangman and the bloodhound look out of their faces. Mistrust all who talk much of their justice! Verily, their souls lack more than honey. And when they call themselves the good and the just, do not forget that they would be pharisees, if only they had—power. (Zarathustra, I. 12)

Now they do have some power, and we have seen what they do with it. As John McWhorter rightly pointed out, they act like pharisees. They use their power to punish, silence, and exclude anyone who disagrees with them. When I see the vitriol of the Elect, I don’t see good intentions. I see vengeance.

Thus I speak to you in a parable—you who make souls whirl, you preachers of equality. To me you are tarantulas, and secretly vengeful. But I shall bring your secrets to light; therefore I laugh in your faces with my laughter of the heights. Therefore I tear at your webs, that your rage may lure you out of your lie-holes and your revenge may leap out from behind your word justice. For that man be delivered from revenge, that is for me the bridge to the highest hope, and a rainbow after long storms. (Zarathustra, I. 12)

Point #4 is so accurate. Equality of inherent worth & dignity never meant denying individual distinctions for earliest Christians. The Apostle Paul uses the analogy of a body functioning in cohesive unity but acknowledging the distinct differences between a hand and a foot in performing distinct functions as part of a shared telos.

Because our hyper-capitalism attaches worth to output, our bizarro-world secular Christendom is focused (at least performatively) on equality of outcomes. Something as obvious as genetic heritability of intelligence is seen as heresy because it denies that each person can achieve equal outcomes. But historic Christianity denies accumulation of material wealth and possessions as a marker of higher worth. Worth is in inherent and God-given. Talents, responsibilities, "giftings", etc are not equally distributed.

Thank you for writing this out so clearly and thoroughly. Makes a ton of sense + clarifies my own intuitions.

As a followup, I'm curious about whether you have any writing where you elaborate on this, ideally from a similarly genealogical point of view:

> In my opinion the scientific enterprise is the greatest achievement of Western culture

Mainly because it strikes me as interesting how the early adherents of the scientific enterprise were also working from deeply Christian moral positions, which similarly became lost to time as science transformed into a secular enterprise. Would love to know more!