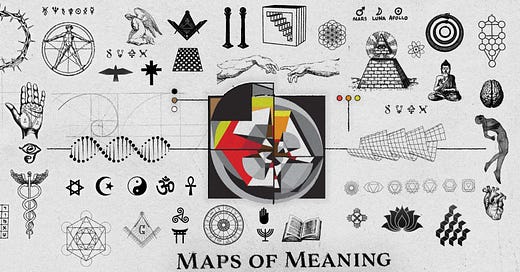

Decoding Jordan Peterson's Maps of Meaning, Part 1

The reconciliation of scientific and narrative conceptions of the world.

*Note: I will switch off between publishing in this series and my series on Nietzsche.

Jordan Peterson’s first book Maps of Meaning (henceforth MoM) is the most important book I’ve ever read. It is also one of the strangest and most difficult books I’ve ever read. In this series of essays I am going to attempt to explain what I think Jordan accomplished in MoM while updating his project by integrating it with scientific literatures he didn’t address. My goal is to simultaneously make MoM more understandable while updating and extending Jordan’s thesis in light of recent scientific advancements.

Some of this will involve discussion of things I’ve already talked about on this substack, including ideas from my essays on consciousness, relevance realization, and the biological function of dreams. I want this series to stand on its own, so you’ll have to forgive me if I repeat myself in places.

In this first essay I will describe the problem that Jordan was dealing with in MoM. On the one hand, Jordan was trying to solve the problem of war. He was intensely concerned — to the point of obsession — with the very real possibility of total nuclear destruction posed by the conflict between the USSR and the Western world:

My interest in the cold war transformed itself into a true obsession. I thought about the suicidal and murderous preparation of that war every minute of every day, from the moment I woke up until the second I went to bed. How could such a state of affairs come about? Who was responsible? (MoM p. 12)

This concern led Jordan to study psychology and eventually to find a new way to formulate his problem. This new formulation is equivalent to the problem of why humans go to war, although that won’t be obvious at first:

The world can be validly construed as a forum for action, as well as a place of things. We describe the world as a place of things, using the formal methods of science. The techniques of narrative, however – myth, literature, and drama – portray the world as a forum for action. The two forms of representation have been unnecessarily set at odds, because we have not yet formed a clear picture of their respective domains. The domain of the former is the “objective world” – what is, from the perspective of intersubjective perception. The domain of the latter is “the world of value” – what is and what should be, from the perspective of emotion and action. (MoM p. 13)

Jordan’s task in MoM is to reconcile these two forms of representation: that of the “objective” world of science and that of the value-laded world of myth, literature, and drama. Both of these forms of representation are conveying truths about the world, he claims, but they have been set at odds with each other because we have not properly conceptualized how they convey that truth. Narrative truth is not scientific truth and vice-versa.

David Hume famously said that you cannot derive an “ought” from an “is”. There is some important sense in which this is true. The particular facts of any situation do not tell you what you ought to do about those facts. Nevertheless, by reconciling the objective world of science with the value-laden world of narrative, Jordan bridges the gap between fact and value, making value judgements continuous with facts about the world.

Jordan does not, of course, demonstrate the value of particular objects. This would be impossible because the value of objects is highly context-dependent. Rather, Jordan demonstrates the objective value of the process by which we determine the value of particular objects. The process itself, which he calls the meta-mythology, is decidedly not context-dependent. Its general contours are the same, regardless of the particulars of the situation.

Jordan demonstrates that narrative representations (i.e., the hero-myths found cross-culturally) are implicitly conveying this process, which simultaneously represents the optimal pattern of behavior in the world. The optimality of this pattern of behavior is fully supported by relevant scientific literatures (e.g., see section 6 of my recent “Intimations” essay). The scientifically supported optimality of this pattern of behavior makes it objectively valuable. If the thesis outlined in this series of essays is correct, this pattern of behavior is optimal (and therefore valuable) regardless of the particulars of your situation and regardless of what you think about it. This pattern therefore serves as a bridge between the value-neutral world of science and the value-laden world of narrative.

The Problems of Communication and War

Jordan was concerned with the problem of war, but this problem is equally the problem of communication. When conflict arises (as it inevitably will), we can either negotiate and find some non-zero-sum solution or we can engage in the zero-sum game of (physical or cultural) warfare. In the evolutionary-developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello’s 2008 book The Origins of Human Communication, he argues that people cannot communicate properly without “shared intentionality”. In other words, we need some common ground (goals, beliefs, etc.) in order to communicate, and therefore we need common ground in order to engage in the kind of negotiation that could ultimately prevent our own nuclear destruction. The increasing political polarization in the Western world is one indicator that this kind of common ground no longer exists.

As John Vervaeke and colleagues suggested in their 2017 book Zombies in Western Culture, Christianity once provided Western people the kind of common ground that facilitates cooperative communication. Religion in general has historically provided cultures with a “sacred canopy” that renders the world meaningful and coherent. The sacred canopy tells us who we are, where we are, and what we are doing here. In the Judeo-Christian model, we are children of God living in a world that is an atonement and preparation for everlasting life in paradise. But the sacred canopy provided by the Judeo-Christian worldview is gone for most people. This not only renders our lives as individuals less meaningful, but also takes away the common ground of Christian identity that made cooperation and communication possible for people across a vast and complex civilization. Nietzsche famously recognized what a great crisis — and opportunity — this loss represented. In his famous parable of the madman, he was trying to convey the gravity of our situation:

The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his eyes. “Whither is God?” he cried; “I will tell you. We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us? Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning? Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. (The Gay Science 125)

In the absence of the “sacred canopy” provided by Christianity (and the shared worldview that came along with it), we are left in a state of chaos. Which way is up? Which way is down? The Christian-Aristotelian worldview provided clear answers to these questions (i.e., transcendence upwards towards the kingdom of God or falling downwards towards the bottomless pit of hell). In the absence of these clear answers, we find ourselves beset by what John Vervaeke has labelled “the meaning crisis”.

This state of chaos is not to be lamented. As with all chaos, it represents a great opportunity as well as a great crisis. It represents the opportunity to create something better — more complex and stable — out of the morass. This is what I see people like Iain McGilchrist, John Vervaeke, and Jordan Peterson attempting to do. I tried to bring many of these strands together in my recent essay “Intimations of a New Worldview”.

There is no going back to what was lost. The Christian-Aristotelian worldview that dominated Western culture for a thousand years is no longer viable to us and never will be again. As Vervaeke and colleagues (2017) put it:

If the worldview of Christianity is eclipsed by secularization, then there is no viable way to recapture its potency as a meta-meaning system. This means that we need to find alternative systems of meaning that provide similar combinations of symbolic provocation, ritual and social fluency. As it turns out, such systems are not easily recreated. You cannot breathe deeply, after all, without an adequate respiratory apparatus. Out from under the canopy, our culture is left gasping in a miasma; finding our bearings in the world, establishing our capacity for action, understanding what is expected of us―these are all Sisyphean tasks… (ch. 5.1)

I see the Sisyphean task of re-establishing meaning in the wake of the loss of the Christian-Aristotelian worldview as the task that Jordan Peterson took on in MoM. He was attempting to solve the problem of war. This is the same as the problem of communication I outlined above, since the only real alternative to communication is war. In order to solve this problem, it would be necessary to re-establish meaning in the wake of Nietzsche’s declaration of the death of God. This would necessarily involve bridging the gap between scientific and narrative conceptions of the world.

And the amazing thing is that I think he succeeded. That is, I think MoM actually provided an outline of a viable solution to the problem. Jordan was fully aware of the importance of this accomplishment, which is presumably why he began the book by quoting the gospel of Matthew: “I will utter things which have been kept secret from the foundation of the world.” (Matthew 13:35)

The first time I read MoM I thought he was being a little bit dramatic by starting with that quote. But the second time I read it, when I really got it, I understood exactly what he meant. He was well aware of what he accomplished in that book. Hopefully when this series of essays is complete, you will be aware of it too.

"There's no going back..." I agree with Peter below....I'm actually not sure that we won't go back. It seems that Christianity has waxed and waned many times over the past 2k years, and we may just be emerging from one of the down cycles. Christianity has integrated many, many scientific breakthroughs which seemed to threaten its very foundations.

Or maybe you're right, and something has irrevocably changed. If so, as much as I admire Vervake, McGilchrist, and Peterson, I'm skeptical that their project will create a new "worldview" that can replace the Christian-Aristotelian frame. Their project is only available to the select few who have cross-cutting knowledge of evolution, cognitive psych, anthropology, philosophy, etc.

Very few people are in the "us" that you speak of. Even most secularists I know have very little understanding of how evolution works. It's both a black box to them and an article of faith. And evolution itself doesn't have the mythical element that's necessary for the emergence of a new worldview. Peterson, Vervaeke, and McGilchrist are wonderful at helping us understand the importance of myth....but they don't have an alternative myth to offer.

I'm sufficiently influenced by Girard that I'd think any new myth would almost certainly arise out of some public act of violence. And it's not at all clear to me that what would come next would be an improvement on the Christian/Aristotelian worldview.

Thanks for these reflections.

Regarding: “There is no going back to what was lost. The Christian-Aristotelian worldview that dominated Western culture for a thousand years is no longer viable to us and never will be again.”

That is certainly one possibility. But demographics and population changes suggest that religious belief (particularly Christian, Islamic, and Jewish) may in fact play an increasing, not decreasing role, both in the West and globally. I have explored that in more detail here: https://peterofbasilea.substack.com/p/cab-crusaders

Separate from that, even if one assumes God is dead (I don’t, but for sake of argument), the underlying problem, which will never quite go away, is whether there is any absolute reference point, beyond our own subjectivity or inter-subjectivity, that gives objective significance to our science and our narratives. Without that, nihilism is always a whisper away.