The Revaluation of All Values, Part 5

Nietzsche's will to power as a process of complexification

This is part 5 of a series that you should read in order.

And do you know what “the world” is to me? Shall I show it to you in my mirror? This world: a monster of energy, without beginning, without end… out of the simplest forms striving toward the most complex… and then again returning home to the simple out of this abundance, out of the play of contradictions back to the joy of concord, still affirming itself in this uniformity of its courses and its years, blessing itself as that which must return eternally, as a becoming that knows no satiety, no disgust, no weariness… my “beyond good and evil,” without goal, unless the joy of the circle is itself a goal; without will, unless a ring feels good will toward itself—do you want a name for this world? A solution for all its riddles? A light for you, too, you best-concealed, strongest, most intrepid, most midnightly men?— This world is the will to power—and nothing besides! And you yourselves are also this will to power—and nothing besides!

— Nietzsche, The Will to Power 1067

It is a strange coincidence that as I was working out the ideas for this series a graduate student in philosophy was working on a dissertation along very similar lines. Sometimes an idea really is just “in the air” and multiple people converge on it. Paul Curtis, in his 2022 dissertation entitled “Nietzsche’s Will to Power: A Naturalistic Account of Metaethics Based on Evolutionary Principles and Thermodynamic Laws” argued that Nietzsche’s will to power thesis is a metaphysical doctrine which provides a basis for making objective value judgements and that the will to power thesis is supported by modern scientific understandings of evolutionary theory and thermodynamics. I have some disagreements with Curtis, especially in his characterization of the dynamic between slave/master morality, but regardless of our differences, his thesis is an original and important contribution to Nietzsche scholarship. His is one of the only attempts I’ve seen to integrate Nietzsche’s “will to power” with modern scientific findings. Let me relay some quotes from his dissertation to give you an idea of what Curtis is claiming:

…in line with the laws of thermodynamics, the universe is always ‘trying’ to dissipate energy gradients, that is to say, bring about equilibrium. We might call this overarching necessity or ‘law’ the ‘will to equilibrium’. Where this is not immediately possible, such as in areas of continual energy release, such as our sun showering earth with energy and heating it, then in these non-equilibrium environments, where constraints allow, ‘nature’ will organise itself into ever-increasing complexities increasing the throughput of energy in the system. This involves an increase of power in the system, and I referred to this as the first manifestation of the will to power. (p. 254)

My evolutionary findings have revealed that the ‘drive’ toward more complex organisms is not a drive to fitness but a drive to power (after all, a unicellular life form is just as ‘fit’ if not ‘fitter’ than a human organism). This drive or will to power is compatible with the second law of thermodynamics, and the maximum power and entropy principles. (p. 255)

As mentioned, power can also be increased via co-operation and symbiosis as well as competition in nature… This leads us to an important finding of my research: the ‘synergy fractal’ in nature. This provides the meta-physical ‘power’ framework that links ‘co-operating’ atoms and molecules, through genes and cells to multi-cellular organisms such as apes and humans who co-operate to form groups, and so on, and it is in these groups that interdependence is realised and ‘morality’ is born. The interdependent group or social organism is a more powerful entity than an individual. (p. 255)

Curtis has argued that an increase in organization and complexity is equivalent to an increase in “power” (we’ll come back to this point later). He has also pointed out the importance of the concept of synergy for understanding increases in power and complexity. Because power is equivalent to complexity, Curtis argues that the greater levels of complexity that inevitably emerge over time can be said to result from an underlying ‘will to power’ that characterizes the evolutionary process.

It’s important not to take the word ‘will’ too literally here or to anthropomorphize. Nobody is claiming that some cosmic being has decided that he likes complexity and is now ‘willing’ the universe in that direction. My claim (echoing Nietzsche) is that the universe just is at bottom this drive, will, or process towards complexity/power. The universe just is most fundamentally that process by which particles became atoms, molecules, stars, galaxies, life, and culture. Everything that exists is a particular manifestation of that general process. The world is therefore the will to power, and nothing besides. You, too, are this will to power, and nothing besides. That is Nietzsche’s claim, and that will be my claim in this post, backed up by modern understandings of evolutionary theory and thermodynamics.

Metaphysics and Value

On the surface, Nietzsche showed nothing but disdain for metaphysics. How, then, could I (or anyone else) claim to uncover Nietzsche’s own metaphysical beliefs? This apparent contradiction is only due to the vagueness of language. The word metaphysics literally means ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the physical. Nietzsche’s criticism of metaphysics was mostly directed at the proposition that there exists some other world beyond the physical world that is more valuable than the physical world. Since I won’t be making any such claim, Nietzsche’s critique of metaphysics won’t apply here.

As I am using the term, metaphysics can be understood as the attempt to frame general laws or principles that will account for the totality of human experience. Unlike scientific research, metaphysics doesn’t add to our body of knowledge. Rather, metaphysics is the attempt to extract the most general principles from our existing body of knowledge. Metaphysics therefore goes above or beyond the physical not by claiming the existence of a realm outside of the physical, but by framing laws or principles that go beyond any particular physical event or object.

The title of this series of articles is “The Revaluation of All Values”. You may reasonably ask what obscure metaphysical claims about complexity and power have to do with human values. The answer to that question won’t become totally clear until later in this series when I will attempt to show that human cognition and social life is continuous with the process of complexification that I will describe in this post. Nevertheless, it’s worth fleshing out why Nietzsche believed that metaphysics was relevant before getting into the the metaphysical claim itself. In part 1 of this series I said that I will attempt to address the problem of nihilism, or the rejection of all meaning and value. In an unpublished note, Nietzsche described three different kinds of nihilism, all of which are related to metaphysical claims:

Nihilism as a psychological state will have to be reached, first, when we have sought a “meaning” in all events that is not there: so the seeker eventually becomes discouraged. Nihilism, then, is the recognition of the long waste of strength, the agony of the “in vain,” insecurity, the lack of any opportunity to recover and to regain composure—being ashamed in front of oneself, as if one had deceived oneself all too long.— This meaning could have been: the “fulfillment” of some highest ethical canon in all events, the moral world order; or the growth of love and harmony in the intercourse of beings; or the gradual approximation of a state of universal happiness; or even the development toward a state of universal annihilation—any goal at least constitutes some meaning…

Nihilism as a psychological state is reached, secondly, when one has posited a totality, a systematization, indeed any organization in all events, and underneath all events… Some sort of unity, some form of “monism”: this faith suffices to give man a deep feeling of standing in the context of, and being dependent on, some whole that is infinitely superior to him, and he sees himself as a mode of the deity…

Nihilism as psychological state has yet a third and last form. Given these two insights, that becoming has no goal and that underneath all becoming there is no grand unity in which the individual could immerse himself completely as in an element of supreme value, an escape remains: to pass sentence on this whole world of becoming as a deception and to invent a world beyond it, a true world. But as soon as man finds out how that world is fabricated solely from psychological needs, and how he has absolutely no right to it, the last form of nihilism comes into being: it includes disbelief in any metaphysical world and forbids itself any belief in a true world. Having reached this standpoint, one grants the reality of becoming as the only reality, forbids oneself every kind of clandestine access to afterworlds and false divinities—but cannot endure this world though one does not want to deny it. What has happened, at bottom?… Briefly: the categories “aim,” “unity,” “being” which we used to project some value into the world—we pull out again; so the world looks valueless. (Will to Power 12)

The first kind of nihilism is reached when we have posited a goal that is inherent in all events (which is a metaphysical claim) and have discovered that this goal is illusory. The second kind of nihilism is reached when we have posited a unity inherent in all events (which is also a metaphysical claim) and have discovered that this unity is illusory. The third kind of nihilism is reached when we have posited another world outside of the physical realm, which gives value to the physical realm (another metaphysical claim), and have discovered that this other world is illusory.

For many modern people, it is no longer possible to believe that the universe has an inherent goal, that the universe is characterized by an underlying unity, or that there exists another world outside of the physical world that is more valuable than the physical world. Because the value of the world, and our own part in it, was tied up with these metaphysical claims for so long, the logical result of our disbelief in them is that the world is without any inherent meaning or value. In this view, Nihilism results from two steps:

1) the dependence of meaning and value on a metaphysical claim, and

2) the discovery that the metaphysical claim is false

Nietzsche’s will to power thesis is a response to the cultural sickness of nihilism, which is why he considers himself to be a cultural physician. I will argue that Nietzsche responds to the problem of nihilism by putting forward an alternative metaphysics (i.e., the will to power) that isn’t subject to the same problems as the metaphysical claims that came before it. This interpretation, however, is pretty controversial among modern Nietzsche scholars.

The Metaphysics of the Will to Power

Some Nietzschean scholars claim that Nietzsche only put his metaphysical claims forward ironically, meaning that he never really believed them (Clark, 1998). I don’t take this idea seriously. I don’t know how anybody can read Nietzsche’s discussions of the will to power and seriously come to the conclusion that he was being ironic. I think this is just a way for scholars who don’t like Nietzsche’s metaphysics to dismiss them without implying that Nietzsche ever had a bad idea. When Nietzsche explicitly wrote about the metaphysics of the will to power, these scholars expect us to believe that he was just kidding around. I’m confident that this is incorrect.

Other Nietzschean scholars claim that Nietzsche was serious about his metaphysical claims but that they are implausible or even “crackpot”. Perhaps the most forceful example comes from Brian Leiter’s 2015 book Nietzsche on Morality:

If it turns out that Nietzsche, the man, really is committed to what seems entailed by the most flat-footed literalism about a bare handful of published “will to power” passages (such as GM II: 12), then so much the worse for Nietzsche we might say. We may do Nietzsche the philosopher a favour, however, if we reconstruct his Humean project in terms that are both recognizably his in significant part, and yet, at the same time, far more plausible once the crackpot metaphysics of will to power (that all organic matter “is will to power”) is expunged… Perhaps Nietzsche really did believe he had some deep insight into the correct metaphysics of nature, one missed by the empirical sciences. If he had that thought—one wholly inconsistent with the rest of his naturalism – so much the worse for him. Those of us reading him more than a century later should concentrate on his fruitful ideas, not the silly ones, especially when they are not central to his important work in moral psychology. (Leiter, 2015, pp. 260-261)

According to Leiter, Nietzsche may have been serious about his metaphysics, but nonetheless it is a “crackpot” and “silly” metaphysics. We would be doing him a favor to ignore or downplay the metaphysics of the will to power because of how implausible it is. Needless to say, I take the third option. I believe that Nietzsche was serious about his metaphysics and that his metaphysics is plausible given modern scientific theory and evidence.

The Metaphysics of Complexity

In order to make my case for the plausibility of the will to power as metaphysics, I will need to establish four points:

Complexity, defined as the simultaneous integration and differentiation of a system, is equivalent to a system’s power.

The universe is characterized by a “drive” towards increasing complexity that can be fully understood through modern thermodynamics.

This drive towards complexity underlies everything that exists.

The drive towards complexity is therefore equivalent to Nietzsche’s will to power.

The next two sections are going to be almost identical to sections 1 and 2 from my “Intimations of a New Worldview” essay because I need to cover the same information for this argument. I’m not going to extensively reword those sections for aesthetic purposes so if you’ve read that essay the following sections will be a little bit repetitive.

What is Complexity?

In his 1997 book The Life of the Cosmos, physicist Lee Smolin argued that the new-found understanding of complexity in physics would forever change the way we understand the world and our place in it. The old Newtonian physics, which led to an understanding of life as an accidental occurrence in an otherwise uninteresting universe, gave way to a new understanding in which life and other complex phenomena were understood as necessary conditions of existence. As Smolin put it:

From the point of view of the old, Newtonian-style physics, the structure of the world is accidental…. But… from the point of view of the new physics, complexity must be an essential aspect of the organization of the world. Indeed, it is not only that a world with life must necessarily be complex… in the twentieth century our very understanding of space and time, of what it means to say where something is or when something happened, requires a complex world. This means that the picture of the universe in which life, variety and structure are improbable accidents must be an outmoded relic of nineteenth-century science. Twentieth-century physics must lead instead towards the understanding that the universe is hospitable to life because, if the world is to exist at all, then it must be full of structure and variety. (p. 16)

Smolin is claiming that complexity — including life — is not an accident or byproduct because complexity is a precondition for any existence at all. What this means is that an explanation of the emergence of complexity is in some sense an explanation of how anything exists at all.

In the late 1980s and 90s, the physicist Per Bak was trying to solve the problem of complexity. The problem can be stated simply. The laws of physics are relatively simple and deterministic. You can write them all down on a single sheet of paper. Given these relatively simple, deterministic laws, why is the universe so interesting? If the laws of physics are so simple, why is everything so complex?

In his 1996 book How Nature Works: The Science of Self-Organized Criticality, Bak put forward a theory on the emergence of complexity in nature. He reasoned that complexity must emerge at the narrow border between order and chaos. A crystal is an example of an ordered system. A crystal is not complex because if you know what one part of the system looks like, then you know what the whole thing looks like. That means an infinitely large crystal can be precisely described with very little information. That’s not complexity. A gas is a chaotic system (keeping in mind that I am not using ‘chaos’ in the technical mathematical sense here). A gas is also not complex. Even though a gas does not have the regularity of a crystal, it is still uniform throughout its entire structure. It looks the same everywhere, and therefore is not complex.

The narrow window between order and chaos at which complexity emerges is referred to as the critical state or criticality. The question, for Bak, was how systems in nature could get to this narrow window without any tuning from an outside agent. We can fine-tune a system to criticality by, for example, precisely adjusting the temperature or other variables. But there is no external agent fine-tuning systems in nature. They must achieve criticality from the bottom-up, through the interactions of the parts of the system and their environment. This is the origin of the term self-organized criticality. Systems in nature self-organize to the narrow window between order and chaos, which is where they become more complex.

Complexity science has made a great deal of progress since Bak discovered self-organized criticality. A 2022 book by Bobby Azarian entitled The Romance of Reality: How the Universe Organizes Itself to Create Life, Consciousness, and Cosmic Complexity brings much of this research together into a coherent narrative. From basic particles to atoms, molecules, stars, galaxies, life, and culture, the universe has clearly become more complex over time. Azarian argues that this process of complexification is not accidental. It is inevitable. As Azarian puts it:

Through a series of hierarchical emergences—a nested sequence of parts coming together to form ever-greater wholes—the universe is undergoing a grand and majestic self-organizing process, and at this moment in time, in this corner of the universe, we are the stars of the show. As cosmic evolution proceeds, the world is becoming increasingly organized, increasingly functional, and, because life and consciousness emerge from sufficient complexity and information integration, increasingly sentient. (p. 5)

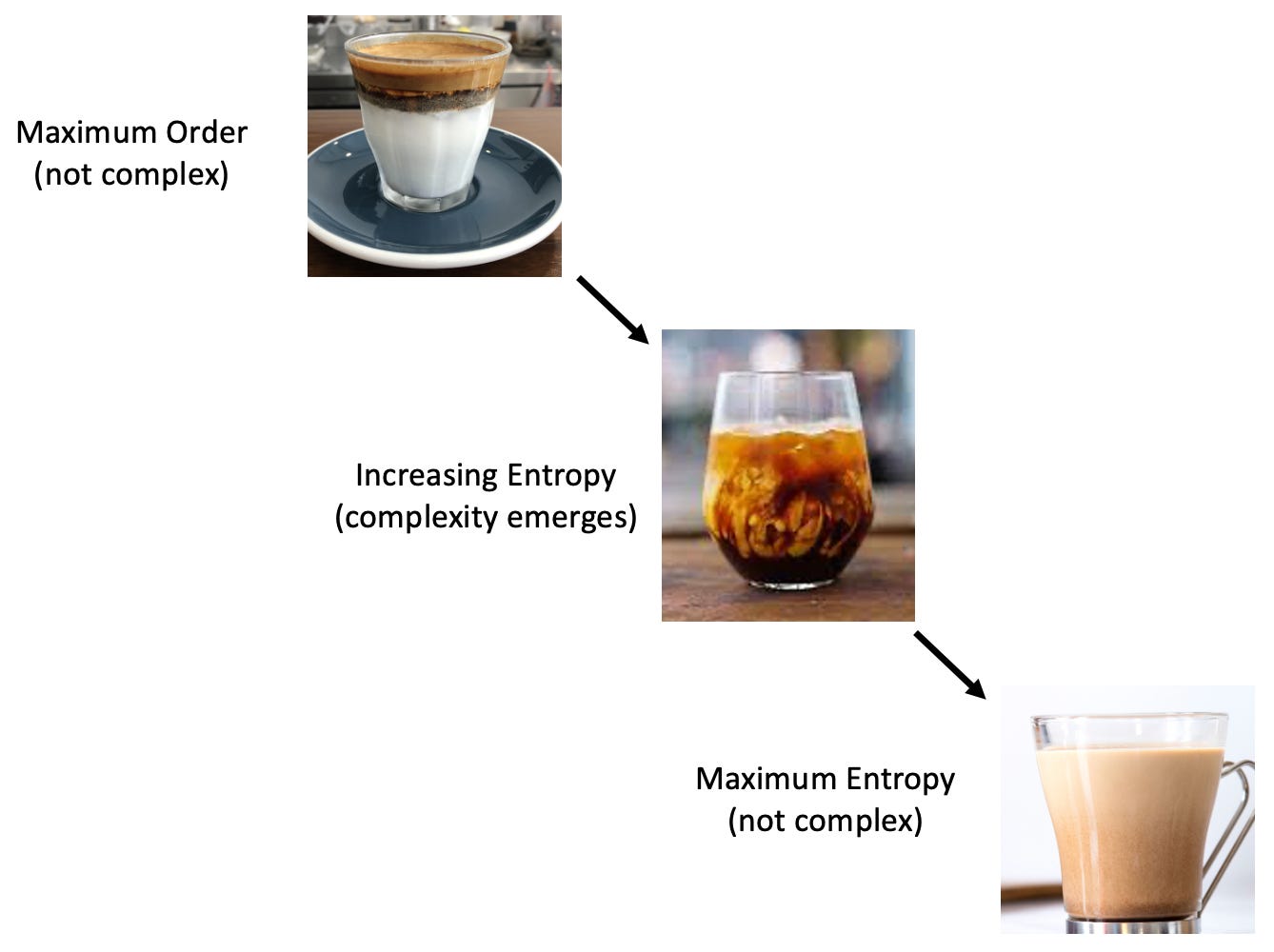

On the surface, this idea may seem as if it somehow violates the second law of thermodynamics. Isn’t the universe becoming increasingly disordered through the inevitable increase in entropy? This seeming contradiction involves a misunderstanding of the relationship between entropy and complexity. Increasing entropy is not opposed to complexity — it is necessary for it. How so?

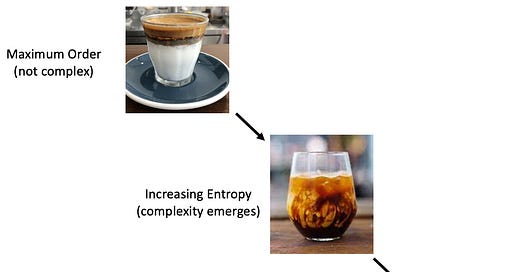

Imagine that you have a cup of coffee with milk in it such that the milk and coffee are totally separated with milk on the bottom and coffee on top. This is a state of perfect order. There is no entropy in this state. It is also not complex because the location of the coffee and milk is perfectly predictable. Now you begin to stir the coffee. This stirring is equivalent to an increase in entropy. As you stir, fractal patterns of swirls appear and it becomes impossible to predict where you will find coffee or milk at any point in time. In other words, the coffee/milk mixture becomes complex. Complexity emerges only while entropy is increasing. Once the mixture is completely stirred, however, there is now a state of perfect disorder (i.e., perfect entropy) and there is no longer any complexity. The position of milk and coffee becomes completely predictable again because they are now evenly distributed through the cup. See the figure below for a representation of this process.

The above figure and explanation of complexity is, not coincidentally, highly reminiscent of Nietzsche’s description of the will to power quoted at the beginning of this post.

Complexity is Power

Complexity is notoriously difficult to define and there are a variety of definitions floating around, many of which are specific to a particular scientific discipline. A general definition of complexity that is used across multiple disciplines is Giulio Tononi’s 1994 definition, which states that a system is more complex to the degree that it is simultaneously differentiated and integrated. For example, a multi-cellular organism is both more differentiated than a single-celled organism (i.e., has more functionally segregated parts) and more integrated (i.e., brings those parts together into a larger functional whole). Thus, a multi-cellular organism is more complex than a single-celled organism. It is that definition of complexity that I will generally use in this essay. To put it simply, integration is order and differentiation is chaos. Complexity requires both. Without integration or differentiation we are left with bland predictability.

An increase in this kind of complexity can be understood as an increase in the power of a system. More complex systems are typically more powerful than less complex systems in the sense that they have more behavioral options available to them and suffer from less internal conflict. For example, as we become more cognitively complex over the course of development (through the insights we achieve), we end up with more behavioral options available to us while simultaneously decreasing internal conflict between competing beliefs and goals (e.g., the goal of losing weight and the goal of having some delicious ice cream). Similarly, as civilizations become more complex through greater specialization of labor (i.e., differentiation) and internal cohesiveness (i.e., integration), they also become more powerful.

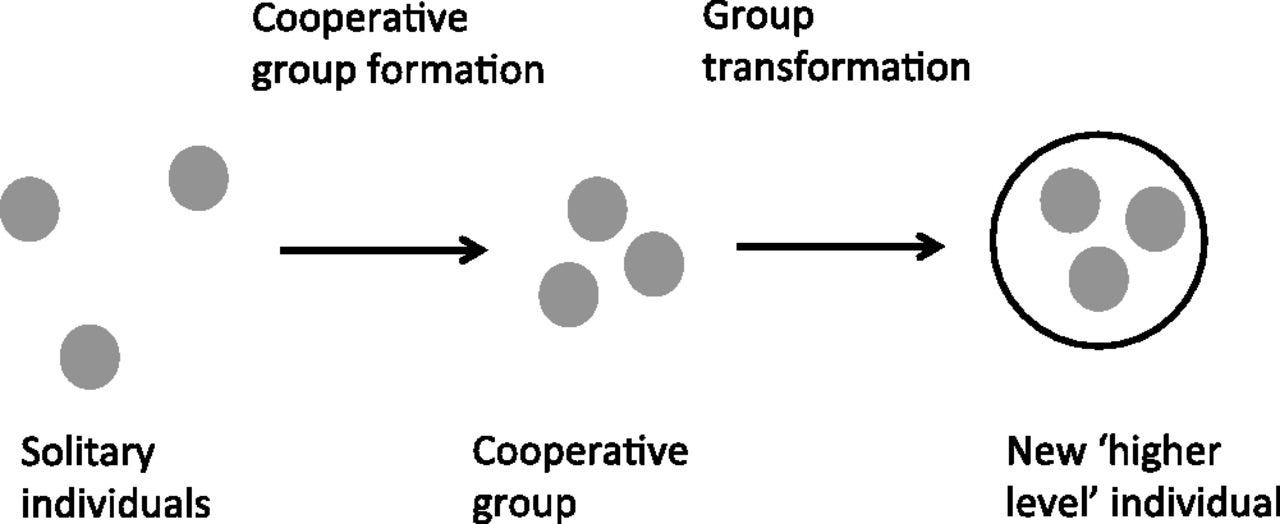

Complexification in biology often manifests as individual entities coming together into groups, which eventually evolve into their own separate entities (e.g., single-celled organisms evolving into multi-cellular organisms), as depicted in the figure below.

In the year 2000 two books were published about the increase in complexity over the course of biological and cultural evolution. These were Evolution’s Arrow by biologist John Stewart and Nonzero by the journalist Robert Wright. Stewart focused on biological evolution and Wright focused on cultural evolution, but both were making a very similar argument. Over the course of biological evolution we have gone from RNA to single-celled organisms to multi-cellular organisms to complex nervous systems, societies, etc. Complexity has clearly increased. Similarly, the last 10,000 years of cultural evolution has seen a massive increase in the complexity of human civilization, from small groups of hunter-gatherers without much division of labor to much larger groups with massive specialization and division of labor.

Both Stewart and Wright claim that biological and cultural evolution have a direction and that direction is towards the increasing scope of non-zero-sum games. The term non-zero-sum comes from game theory and refers to an interaction in which all parties involved have the opportunity to benefit (or experience loss) together. For example, a team of big game hunters in a pre-agricultural group is engaged in a non-zero-sum game. They will either bring down some game for their group or they won’t. And if one of them wins (by having a successful hunt) they all win by receiving meat from that hunt.

As Robert Wright argues in Nonzero, an increase in the scale of a non-zero-sum game is equivalent to an increase in complexity. Why? Because a non-zero-sum game brings entities together (integrates them) and also causes them to specialize (differentiates them). Consider what happens when single-celled organisms come together in the non-zero-sum game that consists of being a multicellular organism. Not only are they more integrated, but over time the different cells of the organism inevitably become more specialized by becoming different kinds of tissues and organs (e.g., muscle cells, nerve cells, etc.). The same thing happens when people come together into larger groups. They inevitably become more specialized (e.g., farmers, blacksmiths, soldiers, etc.). And so an increase in the scope of a non-zero-sum game is equally an increase in both integration and differentiation, i.e., complexity.

In both biological and cultural evolution, we see an increase in the scale and scope of non-zero-sum games over the course of evolution, which is equivalent to an increase in complexity. This brings us back to Paul Curtis’ 2022 disseration on the Will to Power as a basis for morality.

Synergy = Complexity = Power

Paul Curtis does not explicitly discuss non-zero-sum games in his dissertation. Instead, he relies on the concept of synergy to understand the increase in complexity over time. For our purposes, however, the increase in the scope of non-zero-sum games (as discussed by Robert Wright in Nonzero) and the increase in synergy over time are equivalent. They are different ways of talking about the same process of complexification.

To get a grip on what is meant by synergy, we can think about the concept of the division of labor. The most skilled pencil-makers in the world would never be able to compete with the efficiency of many (relatively) unskilled workers performing simple tasks that all add up to a pencil. The division of labor creates a synergistic relationship so that unskilled workers using a division of labor are able to be more efficient than the same number of skilled individuals working separately. Organisms that are able to harness the power of synergy outcompete organisms that can’t. Societies that can harness the power of synergy outcompete societies that can’t. This principle, however, can even be applied to pre-biological entities. The organization of atoms into molecules can also be understood as a synergistic relationship with the ‘goal’ of dissipating energy gradients to bring about equilibrium. Curtis explains:

… in line with the laws of thermodynamics, the universe is always ‘trying’ to dissipate energy gradients, that is to say, bring about equilibrium. We might call this overarching necessity or ‘law’ the ‘will to equilibrium’. Where this is not immediately possible, such as in areas of continual energy release, such as our sun showering earth with energy and heating it, then in these non-equilibrium environments, where constraints allow, ‘nature’ will organise itself into ever-increasing complexities increasing the throughput of energy in the system. This involves an increase of power in the system, and I referred to this as the first manifestation of the will to power. In physics it is known as the Maximum Power Principle, but it is now usually referred to as the Maximum Entropy Production Principle (MEPP). This reveals that, where possible, ‘nature’ will try to organise itself to maximize the power in the system and entropy production. This system of organisation includes the ordering of atoms into constructions of greater complexity—a complexity that I have called a ‘synergy fractal’. (Curtis, 2022 p. 254)

The synergy fractal refers to the fact that as we move up the hierarchy of complexity in nature we see more synergistic relationships. This is the same as the increase in the scope of non-zero-sum games that was pointed out by Robert Wright in Nonzero. It is also the same as an increase in power over the course of evolutionary history. All else being equal, more synergistic systems are also more powerful, as Curtis pointed out in his dissertation:

My evolutionary findings have revealed that the ‘drive’ toward more complex organisms is not a drive to fitness but a drive to power (after all, a unicellular life form is just as ‘fit’ if not ‘fitter’ than a human organism). This drive or will to power is compatible with the second law of thermodynamics, and the maximum power and entropy principles. (p. 255)

We see, then, that the universe is characterized by a drive towards greater levels of synergy/complexity. This drive is not a “goal” per se, but is rather a necessary consequence of the fact that the total amount of entropy in the universe is always increasing.

Back to Metaphysics

Nietzsche’s will to power thesis is a metaphysical claim in the sense that it is an attempt to characterize the most general principle underlying the emergence of everything. As Paul Curtis demonstrated in his dissertation, the claim that everything emerges from an underlying process of complexification is the same as the claim that everything is a manifestation of the will to power. The will to power thesis does, therefore, posit a kind of unity that is inherent in all events (since all particular events are manifestations of the will to power). Nevertheless, it is very different from the metaphysical claims that were undermined to produce modern nihilism. In the first place, the will to power is not the product of divine revelation (as with religious metaphysics) or pure logic (as with the early rationalists). The will to power is instead a generalization of empirical findings. Contrary to Brian Leiter and some other Nietzschean scholars, the metaphysics of the will to power is perfectly compatible with modern scientific understandings of the world. As discussed in part 4, Nietzsche was well aware of the scientific work taking place during his life (e.g., advancements in the knowledge of organic development and the discovery of Darwinian evolution) and this awareness influenced his characterization of the will to power.

Of equal importance is the fact that the will to power is a metaphysical thesis that is totally amoral in the sense that it doesn’t suggest that the universe is headed towards greater levels of peace, love, harmony, or goodness. The synergy fractal discussed by Paul Curtis is driven by war, suffering, death, and competition as much as it is driven by cooperation. Increasing complexity does not imply that the world is becoming more peaceful or that there will be less suffering in the future. In fact, the opposite may be true.

In part 4 I argued that Nietzsche’s will to power thesis was in part a repudiation of Schopenhauer. For Schopenhauer, the suffering and evil inherent to existence are so great that we would all be better off if nothing existed at all. According to Schopenhauer our best option is to extinguish our own will so that we won’t suffer as much. Nietzsche’s mature philosophy could not be more different:

I assess a man by the quantum of power and abundance of his will: not by its enfeeblement and extinction; I regard a philosophy which teaches denial of the will as a teaching of defamation and slander— I assess the power of a will by how much resistance, pain, torture it endures and knows how to turn to its advantage; I do not account the evil and painful character of existence a reproach to it, but hope rather that it will one day be more evil and painful than hitherto… (Will to Power 382)

Here we see a direct repudiation of Schopenhauer’s nihilism. Schopenhauer recognizes “the evil and painful character of existence” and therefore concludes that existence is no good. Nietzsche recognizes the same evil and painful character of existence and hopes that it should become even more evil and painful. But why? Is Nietzsche some kind of sadistic sociopath who enjoys torturing kittens and children? Of course not. Rather, Nietzsche is fully aware of the fact that chaos is both painful and necessary for becoming more powerful (i.e., complexification). Complexity cannot emerge without pain and conflict, and because Nietzsche values the emergence of more complex (i.e., powerful forms he also values the pain and conflict required to produce them.

I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star. I say unto you: you still have chaos in yourselves. (Zarathustra, Prologue. 5)

Creation—that is the great redemption from suffering, and life’s growing light. But that the creator may be, suffering is needed and much change. Indeed, there must be much bitter dying in your life, you creators. Thus are you advocates and justifiers of all impermanence. To be the child who is newly born, the creator must also want to be the mother who gives birth and the pangs of the birth-giver. (Zarathustra, II. 2)

The necessity of chaos for creativity is supported by modern scholarship. For example, there is evidence that a “descent into chaos” (i.e., an increase in entropy) precedes an insight. Stephen and Dixon have shown that insights are preceded by an increase in behavioral entropy and result in a decrease in behavioral entropy such that there is even less entropy than there was before the insight

In the next posts in this series I’ll discuss some examples from Nietzschean scholarship demonstrating the association between power and complexity in Nietzsche’s published writings. A process of complexification can be found in the relationship between master and slave morality and in the process by which an individual becomes more powerful over time.

Hi Brett, I know that your focus generally is on evolutionary psychology with an emphasis on Nietzsche, but have you covered depth psychology and Jung much (I've seen you have made passing references to him)? I would be interested in seeing your more in-depth thoughts on this if it piques your interest. I am also interested in your thoughts, if any, on the interaction between depth psychology and gnosticism which similarly posits a complexification and individuation process. All the best...

Very thought provoking post. How do you see the Nietzschen perspective as a solution to the meaning crisis? Does power bring about meaning and purpose? Is power in itself the only end?

It certainly true that the universe becomes more and more complex. And organisms in it gain more power to execute and control their behaviour. But does the power give a telos for that ability? For what is that capability of action used for?